Read The

Current Issue

Two hundred years after John Colter was the first white man to see Yellowstone and Jackson Hole, two friends retrace his route, find it’s still full of adventure, and make a movie about it.

By Dina Mishev. /. Images from Colter: A legacy of Adventure

ONE OF THE early scouting trips that inspired Wilsonites Sawyer Thomas and Riis Wilbrecht to tackle the adventure that became the twenty-eight-minute film Colter: A Legacy of Adventure was a seven-day winter ski-camping trip in the Beartooth Mountains. “We managed to completely destroy ourselves on it,” Wilbrecht says. Rather than back off though, the pair doubled down. Thomas says, “As soon as we came out from it, I knew I had to go back and do the entire route.”

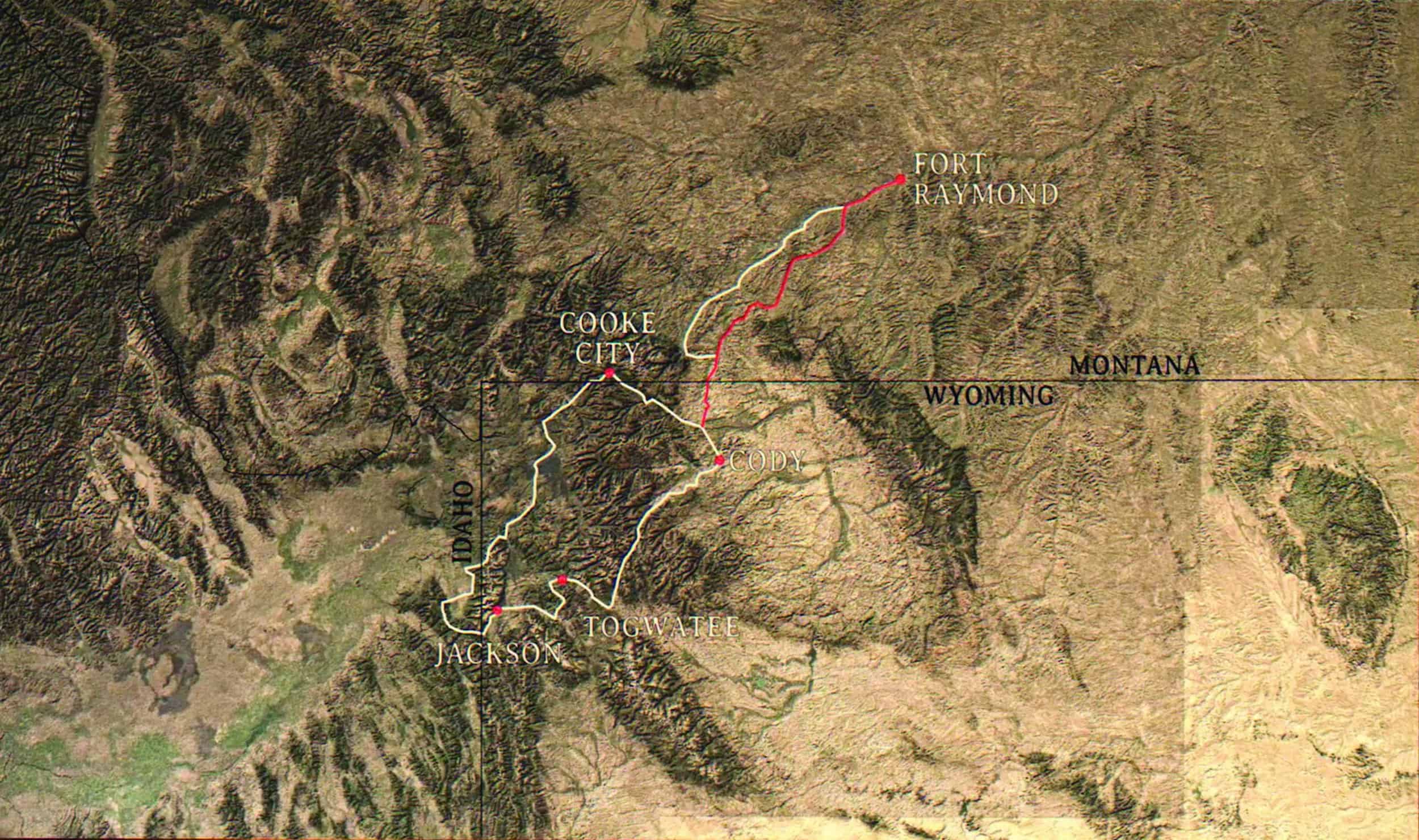

The “route” Thomas refers to is the one believed to have been taken through and around present-day Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks and Jackson Hole over the winter of 1807–1808 by the first white man to see these areas, John Colter. (Read more about Colter, a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition from 1803 to 1806, in the sidebar.) “The whole idea came together over a couple of years,” says Thomas. “I was getting more interested in history and came up with the idea of adding a historical element to our usual mountain adventures. When we came upon Colter’s route, we knew it was perfect. His is an incredible story, and the route went through some of the most amazing terrain we’ve ever been in—exactly the kind of terrain where we wanted to spend time anyway.”

The first big adventure Wilbrecht and Thomas had together was climbing Rock Springs Buttress in the Tetons with Thomas’s father, Charlie. They were in middle school. “Since then, it’s been constant—with running and skiing missions,” Wilbrecht says. “This was our biggest mission by far though.”

It worked for the friends that Colter’s exact route isn’t known. “It gave us flexibility. The ski missions we did and the run were inspired by his route, but also went to places we wanted to go.”

— Sawyer Thomas

WHILE HISTORY WOULD be more clear-cut if the exact route Colter took during the winter of 1807–1808 was known, it isn’t. Colter did not keep journals (he was likely illiterate). Upon his return to St. Louis in 1810, Colter described his route to William Clark, who included it in the 1814 publication A Map of Lewis and Clark’s Track Across the Western Portion of North America from the Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean. And that’s most of what we know about Colter’s solo travels around the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. “About 40 percent of historians think Colter never entered [Yellowstone], and 60 percent think he did,” former Yellowstone National Park historian Lee Whittlesey told National Park Trips Media. Also debated is whether Colter traveled into Jackson Hole via Togwotee Pass or Teton Pass.

“It worked for us that Colter’s exact route isn’t known,” Wilbrecht says. “It gave us flexibility. The ski missions we did and the run were inspired by his route but also went to places we wanted to go.” Thomas says that, after reading various sources, he found historian David Marshall’s book on Colter, Mountain Man: John Colter, the Lewis & Clark Expedition, and the Call of the American West, to be the best researched. “Marshall himself even retraced the route he thought Colter took,” Thomas says. “Marshall’s was the main map we ended up drawing from.”

After months of planning and pouring over maps, the two friends, who went to Wilson Elementary School together and had been making short ski films of each other for years, did several winter ski expeditions at different places around Colter’s route and then, starting May 15, 2019, Thomas began running the entire 600-mile route. (Wilbrecht joined when his full course load at Montana State allowed.) When Wilbrecht wasn’t around, Thomas sometimes ran solo, with his girlfriend, or with other friends or family members. “There were so many people who volunteered their time and helped us out,” Thomas says. (The route actually started, and ended, with Thomas riding about 200 miles on a bicycle, accompanied by his parents.)

Not that the men were expecting the run would be easy, but, “It was a bit of sh—t show from the start,” Wilbrecht says. “Right off the bat, Riis and I really got in over our heads,” Thomas says. The first couple of days of the run, which started outside of Cody, Wyoming, the pair had to cross a river raging with melt off, found the trail they’d planned to follow still buried beneath feet of snow, and would have gotten lost had they not found grizzly bear tracks to follow. And it was raining. “We suffered,” Wilbrecht says.

The only rule of the route was that Thomas had to start at the same place he had finished the day before. There wasn’t an official schedule, but Thomas guesstimated it’d take about one month. “We’d take rest days when I was feeling bad, and I’d do big days when I was feeling good. Everything was planned in the moment,” he says. Weather also affected the schedule. “Wyoming in May can bring anything,” Wilbrecht says. “We posted up in Dubois for two days because it would have been an absolute nightmare to go out and up Togwotee [Pass] in a whiteout.” Thomas says. “It was definitely very unpredictable every single step of the journey. Even on the last day, I wasn’t sure I would make it the entire way, but that’s what makes an adventure.” Watch Colter: A Legacy of Adventure for free at vimeo.com/358862877.

Who Was John Colter?

Little is known of John Colter’s life prior to his joining the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1803, and, even then it’s still pretty fuzzy. Colter likely wasn’t literate, so what we know about him comes from the writings and reports of others. He was born between 1770 and 1775 in the Colony of Virginia and, in 1780, his family moved to present-day Kentucky. Here Colter learned the outdoor survival skills that impressed Meriwether Lewis enough to hire him as a member of the Corps of Discovery.

As a member of the Lewis and Clark expedition, one of Colter’s first significant acts was threatening to shoot fellow corpsman Sergeant John Ordway, which happened even before the group left its base camp at the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers north of St. Louis. Colter was court martialed and faced expulsion, but after apologizing and promising to reform, he was kept on.

For two years and thousands of miles, Colter was one of the Corps’ best hunters and route finders, sometimes persuading Native Americans to work as guides for the expedition. He was one of the few corpsmen who got to see the Pacific Ocean after reaching the mouth of the Columbia River.

In August 1806, Colter was honorably discharged from the expedition, and he set off on his own explorations of present-day Montana and Wyoming. For four years, he explored solo, guided others, trapped, and traded. It was the eight months of winter he spent alone in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem that he is best known for and that make the argument for him being the first “mountain man,” a particularly adventurous and skilled breed of Rocky Mountain explorer that peaked in number and popularity in the 1840s.

Colter returned to Missouri in 1810 and, within a year, was married to Sallie (or Sarah, or Sally) Lucie (or Lucy). The couple had a son, Hiram, and settled on the Missouri River. One of their neighbors was an elderly Daniel Boone. Colter died of an unknown illness in 1812. JH