Read The

Current Issue

An Oasis in East Moose

Enduring for nearly a century, Dornan’s has aged like a fine wine.

By JIM STANFORD

IN JULY 1918, as the Allies fought a battle along the River Marne that would prove decisive in ending World War I, a young woman on leave from her job in a warplane factory first laid eyes on the Snake River.

Evelyn Middleton Dornan took a furlough from the League Island Navy Yard in Philadelphia and traveled by train to Victor, Idaho. After an all-day stagecoach ride over Teton Pass, she arrived in Moose to stay with Maud Noble, operator of Menor’s Ferry.

“The scenery is wonderful, the flowers, birds and mountains sublime and the water all live streams,” Evelyn wrote in her diary on July 29.

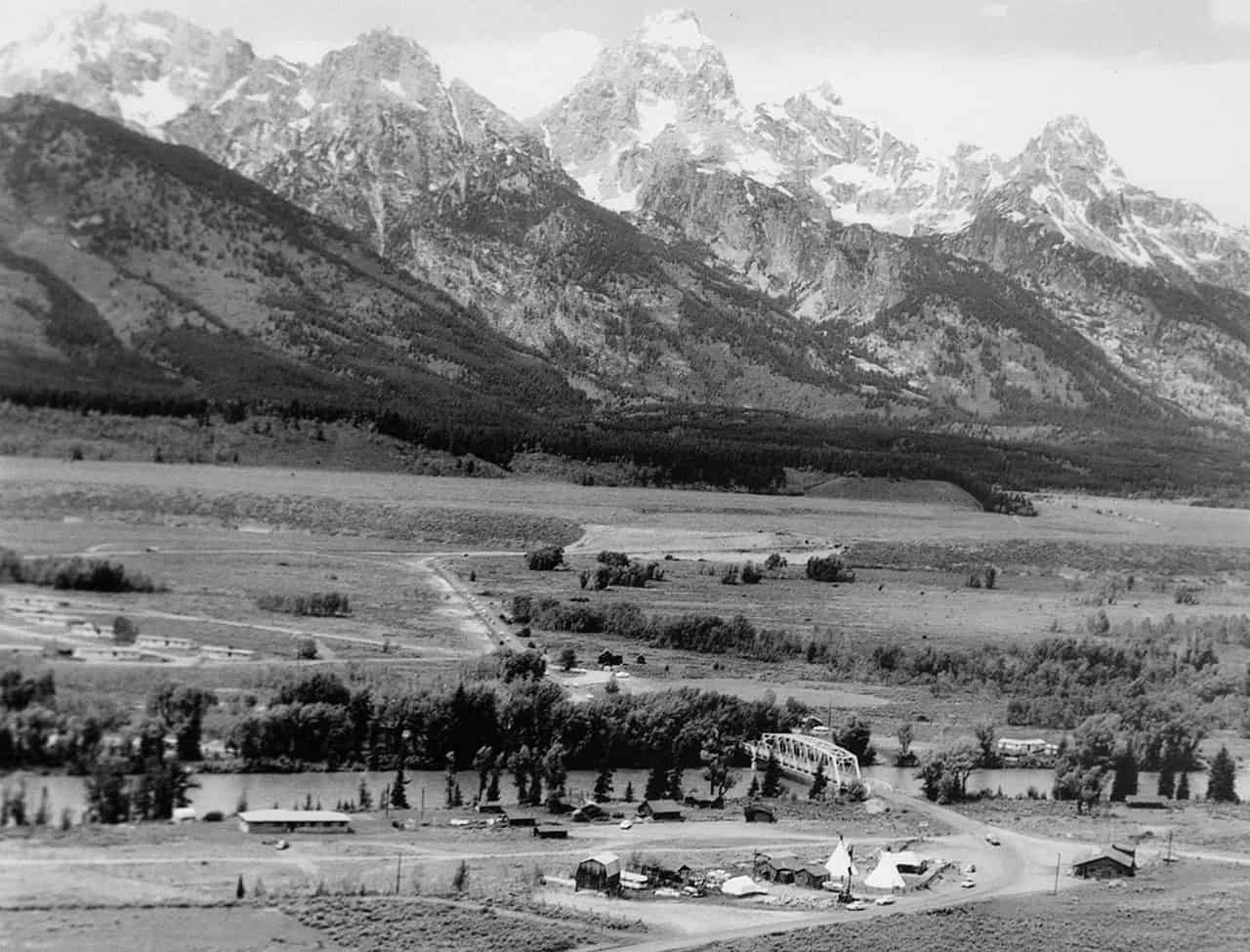

The vacation with Noble, a fellow Philadelphian, left a deep impression on Evelyn. Three years later, the war over and her job making wing panels for airplanes finished, she returned to the Tetons and planted roots. Evelyn homesteaded on the east bank of the Snake and started a family enterprise that nearly a century later is a Jackson Hole institution. The iconic compound, an inholding within Grand Teton National Park (GTNP), remains surrounded by scenery nearly as sublime as when she first set foot in the dusty sagebrush.

Today Dornan’s has a bar and restaurant, wine shop, grocery store, gift shop, gas pumps, the outdoor Chuckwagon restaurant, family homes, guest cabins, and several retail and rental shops. The place buzzes with tourists in summer but is much quieter in winter, bounded by tall banks of snow.

The bar, with its sweeping view of the Tetons, is a cherished watering hole where generations of climbers, hikers, skiers, and river runners have gathered to share tales over post-adventure refreshments.

LIKE MANY OF the early pioneers on nearby Mormon Row, Dornan eked out a living amongst the sage and river cobbles. As a veteran of the war effort, she received preference for homesteading and staked a claim to just over twenty acres south and east of the ferry Noble ran. There was an abandoned blacksmith’s shop on the site, walled on three sides and with a sod roof and dirt floor. She refurbished the cabin, put in a heating stove, and fenced the property. She grew rhubarb, which she canned and sometimes traded for other goods, as well as carrots, cabbage, and rutabagas.

Jackson Hole was her summer home. Evelyn spent winters in San Diego. One of eleven siblings, she inherited money from her father, an industrialist, and came West looking to start over after a divorce. “She was the only one of her family with enough gumption to get out of Philadelphia,” her grandson, the late Bob Dornan, recalled earlier this year.

She and her husband, Jack P. Dornan Sr., divorced when their son, Jack, was about eight or nine years old. Before his final year of prep school, Jack Jr. came out to visit his mother in Wyoming. The experience was transformative, and by the end of summer he abandoned his plan to attend West Point and chose to instead become a cowboy. His mother gave him fifty dollars to buy groceries to get him through the winter. With the help of neighbor Holiday Menor, whose brother, Bill, built the namesake Menor’s Ferry in 1894, he survived. He fed and saddled horses and harnessed a team for Menor.

Jack Dornan built the family homestead into a business. In 1927, he married Ellen Jones; the couple were the first wed in the Chapel of the Transfiguration. Ellen was the daughter of J.R. Jones, a self-taught writer and poker player raised in the California gold camps. Jones homesteaded in Jackson Hole in 1906 and was part of the famous July 1923 meeting in Noble’s cabin that led to the formation of Grand Teton park.

Jack Dornan worked for the Forest Service, helped build the Death Canyon trail, and cut logs from Timbered Island and near Jenny Lake (before Congress established GTNP in 1929). He learned to lay logs and built three log cabins, which were rented out to guests. The place initially was called the Spur Ranch—hanging on the wall of the bar is a framed pair of World War I British Cavalry spurs, given to Evelyn by a soldier with whom she may have had a romance.

Dornan’s might not be the landmark it is today were it not for several twists of fate. In the fall of 1928, the family went to San Diego and Jack found work at a car dealership. Ellen gave birth to the couple’s eldest son, Bob, in June 1929. Jack was a good salesman and had plans to expand the business to Arizona, but the stock market crash that fall quashed sales, and the family returned to Jackson Hole.

Jack borrowed money from Grace Miller, Jackson’s first female mayor, and started a short-lived trucking business with Paul Petzoldt, the famous climber, who rented one of the cabins. With tourists beginning to stream into the newly created national park, Jack opened a service station on the property with a lunch counter and beer parlor. In the fall of 1941, he built the log building that now houses the grocery store. A partner, John Mears, was securing financing to open a casino there.

On Dec. 6, 1941, they laid the last log of the store. The next day, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and “the world went to hell,” Bob Dornan said. The store sat roofless for years, and the family moved to Idaho so Jack could work for a military contractor.

After the war, the Dornans returned home and finished the original store and bar. In the summer of 1946, a man who had made money in the Yukon gold rush negotiated to buy the property for $33,500. He said he would return in the morning to sign the papers but never showed. Evelyn eventually deeded nine and a half acres to Jack and sold the rest to the Park Service.

The Park Service made several attempts to buy the entire parcel, but Jack resisted. A tense exchange took place in the early 1950s when superintendent Ed Freeland stopped by Dornan’s and delivered an ultimatum: sell or be forced out. A young Bob Dornan expected his dad to pull out the six-shooter he kept beneath the bar. Instead, Jack pointed toward the exit. “I’ll have this property after you’re dead and gone,” Bob recalled his father saying. “See that door over there? I want you to go out that door and never set foot in this building again.”

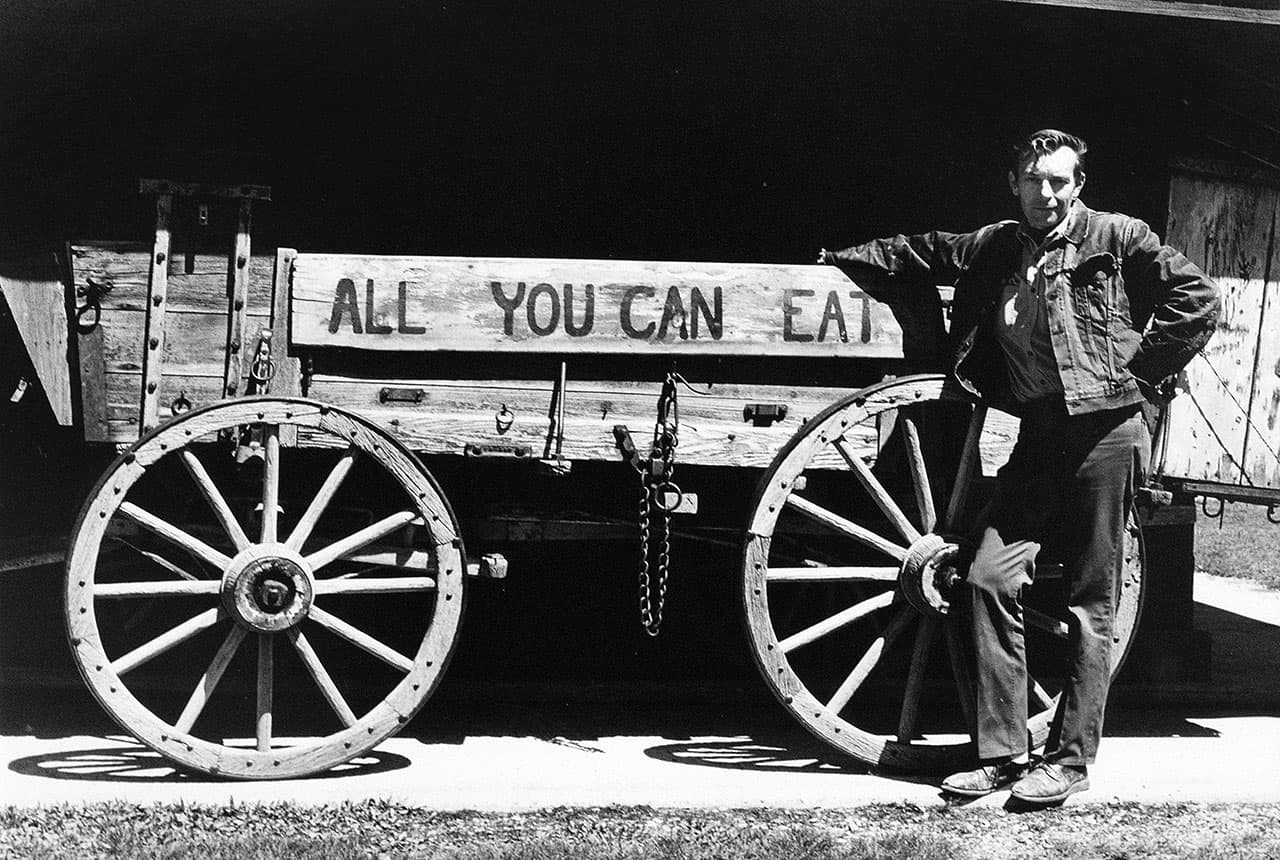

OVER TIME, DORNAN’S expanded its offerings. The outdoor Chuckwagon restaurant, famous for its beef short ribs and mashed potatoes cooked in Dutch ovens over an open fire, opened in 1948. Three men from Riverton—the Warpness brothers, who had operated a similar eatery at Flagg Ranch—ran the chuckwagon before the Dornans took it over. Beginning in the 1960s, the relationship with the Park Service improved. The current bar (built by Bob Dornan and brother Dick), indoor restaurant, and wine shop were added in 1978, followed by the gift shop in 1987, and new cabins in 1992.

SINCE THE 1950s, Dornan’s has carved out a niche as a vendor of fine wines. Eastern dudes, many of them staying at the Whitegrass Ranch, often brought their own wine with them. Jack Dornan saw an opportunity. Malcolm Ramsay, the first husband of late Jackson Hole News&Guide copublisher Elizabeth McCabe, lived in Napa Valley, California, and introduced Dornan to some of the region’s winemakers. As tourism in Jackson Hole grew, “All these damn Californians wanted their California wine,” Bob Dornan recalled. Dornan’s became the go-to supplier for many of the valley’s most genteel guests.

Bob Dornan learned the business from his father and began making trips to California in the late 1960s. He became a noted oenophile. “We wouldn’t buy wine unless we could taste it,” he said. By the 1990s, representatives from the wineries were traveling to Moose, and Dornan held court at the front table of the bar, a large selection of wines spread out before him for tasting.

JACK AND ELLEN had seven children, one of whom, Dick, continues to work at the enterprise today with his wife, Tricia. Several other family members also have a hand in the business. Huntley Dornan, great-grandson of Evelyn, serves as CEO.

Much of the early history was passed down orally by Bob Dornan, a kind-hearted grizzly bear of a man who died of cancer in September at age eighty-six. Known for his cowboy hat, round glasses, and pearl-button shirts as much as his liberal use of expletives, he was a bridge to a bygone era.

The “live water” of the Snake still trickles by Menor’s Ferry and Dornan’s each winter. In a time when the valley has seen dizzying changes, Dornan’s, to the relief of many, has maintained its charm. “We don’t try to change too [damn] much,” Bob Dornan said a few months before his death. “We purposefully keep a low profile.”

Tastes from the vine

Bob Dornan has passed, but the wine tradition lives on at Dornan’s under the guidance of wine shop manager Dennis Johnson, who has been with the business since 1985. From 6 to 8 p.m. on the first Sunday of every month, Dornan’s hosts Wine Tasting on a Budget. The cost is $10 to taste several reds and whites priced under $20. Participants receive a coupon for $5 off one of the featured bottles.

Dornan’s also hosts a monthly wine dinner, usually on a Saturday night in the middle of the month. The cost for food and wine is $85. In February, A to Z Wineworks and Oregon’s Rex Hill will be featured. dornans.com, 307/733-2415