Read The

Current Issue

Buried in Jackson

A history of some of the valleys cemeteries

By Emily Mieure

The Allen Cemetery at Moran is a 3-acre plot now under ownership of the National Park Service. It was the original family cemetery of Maria and Charles Allen, who settled there in 1896. Photo by Jackson Hole Historical Society & Museum

In 1973, California resident Marianne Cotter wrote a letter to the editor of The Jackson Hole Guide. “I have decided that if I can’t live in Jackson Hole, I’ll be buried there,” she wrote. “My next question is, where is the cemetery?” Cotter probably didn’t realize that being buried in Jackson Hole might be even more difficult than living here. The valley has dozens of private cemeteries on ranches and former homesteads, but only one public cemetery. Much of what we know about the valley’s cemeteries, whether public or private, dates from work by volunteer surveyors from the Jackson Hole Historical Society & Museum (JHHSM). In the early 1990s, Sharon Lass Field and Polly McLaren scoured the valley looking for gravesites. They took detailed, handwritten notes—that still live at the JHHSM in both original and digital forms—on about eight cemeteries, some with as few as four known graves. [Editor’s note: This is not a complete list of gravesites in Teton County.]

1. Aspen Hill Cemetery

The only public cemetery in Jackson is tucked between ski runs on the lower slopes of Snow King Mountain. The first plot here was dug in 1905—thirty-five years before Snow King Mountain opened as the first ski area in Wyoming—after an informal agreement between unknown persons. “They just bushwhacked their way up here to bury some of the early folks,” says Al Zuckerman, who has been Aspen Hill’s sexton since 1998. By 1920, thirty-seven people had been buried here and the Town of Jackson officially acquired the land—13.27 acres—from the U.S. Forest Service. There are about thirteen graveside services here annually now, and mourners must stand on the switchback nearest the grave because the hillside is too steep for most people to climb or comfortably stand. Today anyone can be buried here—about 1,390 people already are—but, to reserve a plot, you have to be already dead or dying. Zuckerman says there are about eighty-seven gravesites left.

2. Elliott Cemetery

Longtime Wilson families are buried at Elliott Cemetery, which sits in the woods at the base of Teton Pass. Located on the former John Elliott homestead, the first graves were dug here in 1902. Elliott lost two sons, Clark, 4, and James, 13, to diphtheria and buried them on a bench behind his homestead. Over the ensuing decades, other long-time Wilson families including the Schofields and the Huidekopers donated adjacent land. It is not known how many people are buried here, but most are Wilson homesteaders and their descendants. Field noted in her survey that Pony Express riders and outlaws were likely buried here, too.

3. South Park Cemetery

This is the oldest cemetery in Jackson Hole. Its first graves were dug in 1891 for siblings Ella and Joseph Wilson, both of whom died from diphtheria. (Deaths from diphtheria were not limited to the 1902 outbreak mentioned in the sidebar on p. 98.) In 1889, this cemetery was dedicated to Ella and Joseph’s parents, Sylvester and Mary Wood Wilson, who were one of the couples that led the first families over Teton Pass to settle in Jackson Hole. In 1895, Sylvester was buried alongside his children. His headstone reads, “Was a minuteman in every sense the word implies.” Today there are about three hundred people buried here; the most recent graves date to the late 1990s.

4. Kelly Cemetery

This cemetery is on a dirt road on the eastern edge of Grand Teton National Park northeast of Kelly. A gate, a barbed wire fence, and a sign that reads, “Please keep gate closed,” are the only markings here. When it was discovered that at least one dozen veterans of World Wars I and II and the Korean War are among those buried here, American Legion Post 43 began visiting every Memorial Day. The first people to be buried here were the six who died in the massive 1927 Kelly flood, which was caused when the natural dam across the Gros Ventre River created two years prior by the Gros Ventre Landslide failed. The cemetery is now within the boundaries of Grand Teton National Park.

5. Moran Cemetery

This 3-acre graveyard is the only remaining evidence of Maria and Charles Allen’s 1896 homestead. When the Allens sold their ranch here in the 1920s, there were already several family members and close neighbors buried here, so they retained the title to this part of their property. (Both Maria and Charles were eventually buried here.) In 1958, the cemetery was sold to the National Park Service and one condition of the sale was that up to twelve additional descendants of the Allen family be allowed to be buried there.

6. Granite Ridge Cemetery

A now-overgrown cemetery with two or three dozen known graves near the base of Jackson Hole Mountain Resort in Teton Village has its roots in the 1902 diphtheria epidemic. Ellen Magnum might be the last known burial here, in 1968 … but maybe not. Magnum also has a headstone in Elliott Cemetery, where it is believed her husband, Albert, was buried after his death in 1931.

7. Hunter Hereford Cemetery

This small, private cemetery off Antelope Flats Road near Shadow Mountain was established in 1951. William Hunter died of a heart attack while working on his cattle ranch, and his wife, Eileen, wanted to bury him near their house. In 1987, Julius Mosley, who built the famous Hardeman barns in Wilson, was laid to rest here.

8. Conrad Schwiering Cemetery

This cemetery on a hill on former ranchland near Shadow Mountain only has four known graves. “A lovely statute of the Virgin Mary stands guard over the small burial ground, surrounded by aspens and pines,” surveyor McLaren noted in 1991. Conrad Schwiering, an accomplished landscape painter who opened a small gallery inside Jackson’s Wort Hotel in 1948, and his wife, Mary Ethel, were buried here in 1986. They owned the property at the time. This land is still privately owned.

9. St. John’s Episcopal Church Columbarium

Cremation is now more common than casket burials in Teton County. Valley Morturary owner Scott McKague says 85 percent of people here now get cremated. St. John’s Episcopal Church built a columbarium using stone quarried in Kemmerer, Wyoming, in 1997.

10. Our Lady of the Mountains Columbarium

Our Lady of the Mountains built a columbarium in 2010. “The columbarium was installed to memorialize members of our parish and to hold remains,” says the church’s business manager, Tamra Hendrickson. “The other thing we found is if someone passes in the dead of winter here, it’s easier to inter their remains [than bury them].”

11. Yellowstone burials

At least two people are buried in the Teton County, Wyoming, portion of Yellowstone National Park. Bessie Rowbottom, 3, died on July 6, 1903, and is buried near the South Entrance. In an unknown year, Private Harry Allen, a member of the Army who was stationed in Yellowstone, and another man, W.B. Taylor, of Bozeman, Montana, were in a rowboat that capsized on Yellowstone Lake. They drowned, and park historian Alicia Murphy says their bodies weren’t recovered for at least a year. Soldiers later buried body parts identified as Allen’s in a grave north of the West Thumb Geyser Basin.

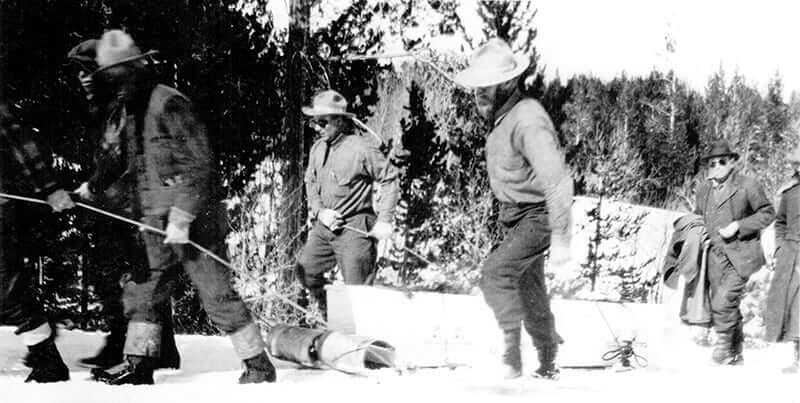

A toboggan funeral procession on its way to the Allen Cemetery, now known as Moran Cemetery. Mr. and Mrs. James Budge follow the procession, which was for their son, Bert. Photo by Jackson Hole Historical Society & Museum

Diphtheria

A couple of the earliest cemeteries in the valley were founded to bury residents, mostly children, who died in a 1902 diphtheria outbreak. Successful treatment of humans infected by the diphtheria bacteria started in 1894, after German physiologist Emil von Bering developed an antitoxin derived from the blood serum of horses. (Fun fact: In 1901, von Bering earned the first-ever Nobel Prize in medicine for his work on diphtheria.) But, in 1902, use and availability of the antitoxin had slowed. The year before, 10 of 11 children inoculated with the antitoxin in St. Louis died. It had been contaminated with tetanus. At that time there were no controls or regulations to ensure an antitoxin’s purity. (In 1902 Congress passed the Biologics Control Act in direct response to the contamination that had happened in St. Louis.)

In 1902, diphtheria broke out in Jackson Hole and many other places in the country. No one knows for sure how many locals this outbreak killed, but diphtheria is highly contagious—it’s usually spread by direct contact or through the air or contaminated objects—and had a mortality rate of about 10 percent. The mortality rate was even higher for children under 12. We do know that the first burials at the Elliott, South Park, and Granite Ridge Cemeteries were of children who died from the infection.