Read The

Current Issue

Women on the Walls

Women gallerists and curators make Jackson Hole’s art scene more vibrant.

// By Dina Mishev

“There are great artists who, throughout history, have gotten the short end of the stick,” says National Museum of Wildlife Art curator of art, Tammi Hanawalt, PhD. “They were well-known in their time but were then left out of the art history and survey books.” What artists is Hanawalt talking about? Women. (And this could be said for any minority, as well.)

In the 572-page first edition of History of Art by H.W. Janson used in most art-survey courses in U.S. colleges and universities, there wasn’t a single female artist included. (The first edition was published in 1962.) By the time the sixth edition was published in 2006, among the hundreds of artists whose stories were told and work admired were 16 women. The British equivalent of Janson’s art-survey book, The Story of Art by Ernst Gombrich, was/is even worse. First published in 1950, its 800-some pages don’t include a single mention of a female artist. As of 2024, The Story of Art is in its 16th edition, which includes one woman artist. Historically, creating art was more difficult for women—women artists in Europe weren’t even allowed to be admitted to the life-drawing studio until the 1890s—but there were women who persevered. “There were women who were accomplished, professional artists despite everything against them,” says Shari Brownfield, founder and owner of the Jackson-based boutique art advisory and appraisal firm Shari Brownfield Fine Art. “But they’ve been left out of our history books.”

It’s not just history that is hard on female artists. In the present, of the 3,050 art galleries in Artsy’s database (Artsy is a New York City-based online art brokerage), 10 percent represent not a single female artist and almost half represent 25 percent or fewer women. According to the 2024 Artnet Intelligence Report, only 11 women were among the 100 top-selling artists at auction globally in 2023. Working female visual artists today earn, on average, seventy-four cents for every dollar made by male artists. Recent data from the National Endowment of the Arts reveals 89 percent of museum acquisitions and 85 percent of museum exhibitions in the U.S. are dedicated to male artists.

If these facts and statistics are a surprise to you, you’re not alone. “The under-representation of women in art didn’t dawn on me when I was in art school,” Brownfield says. “It wasn’t until I was working in larger galleries that I realized it was almost entirely male artists that I was selling, and the few times I had requests for work by female artists, it was typically for the same few women—and their prices were significantly lower than their male counterparts. The more I paid attention to this, the more I began to believe that they were not collected and not expensive for no other reason than that they were female artists and their stories hadn’t been told.”

While the macro story of females in art is sobering, Jackson Hole’s art scene—from its galleries to the National Museum of Wildlife Art and artists themselves—could be viewed as a beacon of hope. The top two curatorial posts at the NMWA are held by women, and the museum is actively trying to increase its representation of women and minorities in its permanent collection and in temporary exhibits. Of the 25 member galleries of the Jackson Hole Gallery Association, seven are owned or run solely by women and a handful are owned by husband-and-wife teams. There are four galleries founded and run by women artists (Ringholz Studios, Gallery Wild, Turner Fine Art, and Thal Glass Studio). The leader of the nonprofit Jackson Hole Public Art is a woman (Carrie Geraci), as is the executive director of the Jackson Hole Art Association (Jennifer Lee), which annually teaches about 220 art classes a year to more than 1,000 students of all ages. Hit one of the Art Association’s two summer Art Fairs and you’ll see an almost equal number of male and female artists. Same for the NMWA’s Plein Air Fest, Etc. “Our town has so many talented women in leading roles in the visual arts, which is really an incredible thing,” Brownfield says.

“There is a very high percentage of women-owned and women-run galleries in Jackson Hole, which is exciting.”

—Mariam Diehl, founder of Diehl Gallery

Hanawalt says this improves the Jackson Hole art scene. “I think with any art experience, the more perspectives you have, the more your experience is enhanced,” she says. “If I see a lot of different perspectives, that can only enrich my experience. And it makes me more aware of the whole world instead of just a little piece.”

Two decades ago, two subject matters, painted traditionally, dominated Jackson Hole’s art scene—the West and wildlife. Today, you can still find traditional takes on Western and wildlife art in our galleries, but there are also galleries that represent artists painting and sculpting these subjects from nontraditional perspectives. And there are galleries that don’t have a single piece of art with wildlife, cowboys, or Native Americans in them. Brownfield credits the valley’s female gallerists for this evolution. “It’s not impossible for women to relate to cowboy art, but they are often male-dominated deals,” she says. “I think the women running galleries here went looking for art and artists they felt they related to more and they were more passionate about, and that still held a sense of place yet expressed it in a different manner.”

Mariam Diehl is one such gallerist. She bought the Jackson Hole Meyer Gallery in 2005 after having been its director for several years. Founded in Park City in 1965 and expanding with a Jackson branch in 2001, Meyer Gallery represented many of the finest traditional Western and wildlife artists. After purchasing the Jackson location, Diehl spent several years slowly transitioning its roster of artists to be more contemporary. In 2005, she told the Jackson Hole News&Guide, “I had been doing research on artists for some time—artists whose work I liked or who I had heard great things about—and as soon as it seemed likely I was going to get the gallery, I started tracking them down.” When she had fully transitioned the gallery, in 2008, Diehl renamed it Diehl Gallery. “At that point, I felt that the artists in the gallery were all ones that I really loved and whose work I was passionate about.”

The fact that Diehl Gallery’s stable of artists fluctuates between 30 and 50 percent women is a bonus. “I do make a conscious effort to represent women artists, but not at the expense of the quality of the art in the gallery,” she says. “It is most important to me to represent talented artists and artwork that I really love rather than focus on the sex of the artists I represent.” Which perhaps is the goal of any woman artist. One of painter Georgia O’Keeffe’s most well-known quotes speaks to this: “Men put me down as the best woman painter. I think I’m one of the best painters.”

Rosa Bonheur and Women Wildlife Artists

In 2022, the National Museum of Wildlife Art curated the exhibit Bonheur & Beyond: Celebrating Women in Wildlife Art, which highlighted work in its permanent collection by women artists. Among the artists included was Rosa Bonheur, who was “one of the most famous women artists of the 19th century and one of the most esteemed animal painters in history,” says the museum’s curator of art, Tammi Hanawalt, PhD.

Bonheur (1822–1899) was the eldest of four children born to an artist father and a piano teacher mother. The family lived in Paris, and when she was 14, Bonheur began to study art at the Louvre. In 1841, when she was 19, Bonheur made her debut at the prestigious Paris Salon, and within several years her work was in demand by collectors. Her 1848 painting Plouging in the Nivernais hangs in the Musée d’Orsay, and her 8-by-16-foot painting The Horse Fair hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. (At the time of its debut, an American publication called the latter nothing less than “the world’s greatest animal picture.”) The NMWA has six pieces of Bonheur’s in its permanent collection.

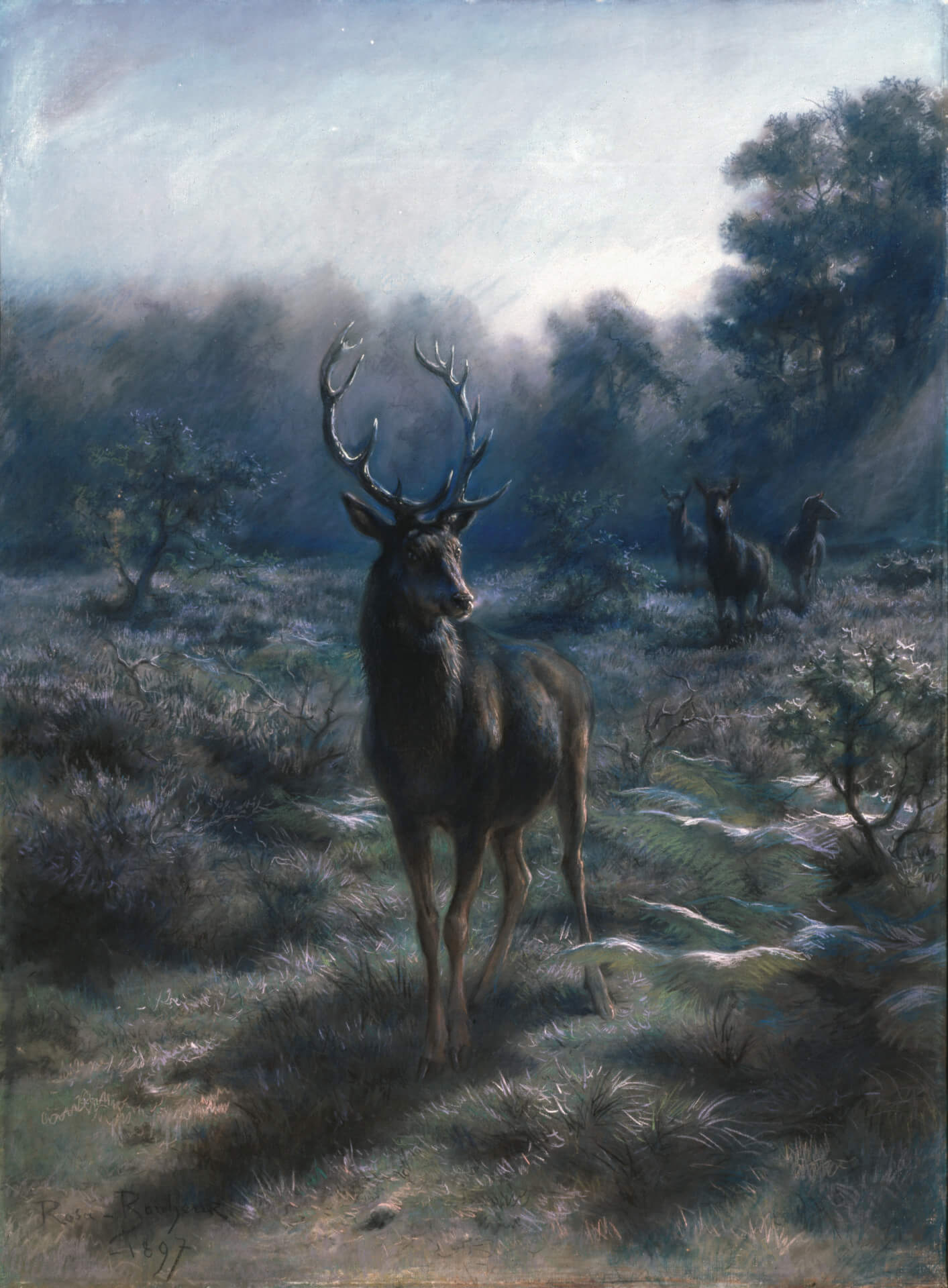

While Bonheur & Beyond: Celebrating Women in Wildlife Art is no longer on display, plenty of works by women artists are part of the permanent collection, including Bonheur’s King of the Forest. “[Bonheur’s] command of naturalism is evidenced in the way she painted the unique qualities of her subject matter,” Hanawalt says. “She painted animals’ vitality, their life force—it was how she showed her respect.”

Here are three other female artists to look for at the NMWA:

Harriet Whitney Frishmuth (1880–1980), who studied with August Rodin at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, collaborated with sculptor Karl Illava on Diana (The Hunt). In the work, Diana, the goddess of wild animals and the hunt in Roman mythology, clasps a bow and appears to float atop of, or run above, two wild wolfhounds. Frishmuth sculpted Diana; Illava sculpted the two wolfhounds.

Anna Hyatt Huntington (1876–1973) spent countless hours observing a jaguar named Señor Lopez at the New York Zoological Society (now the Bronx Zoo) as the model for two sculptures in the museum’s permanent collection, Jaguar and Resting Jaguar. Huntington was a significant American artist in the early 20th century but, “her accomplishments, like Bonheur’s, have been overlooked historically,” Hanawalt says. “She was not necessarily promoted as the skillful and creative artist that she was.”

The museum has six works by Lander-based artist Sandy Scott in its permanent collection, including two sculptures on its sculpture trail, the monumental-sized Presidential Eagle and Sovereign Wings. “She is an important artist of our time who continues to create large installation piece sculptures,” Hanawalt says.

Other women artists to look for on display include Georgia O’Keeffe, Lindsay Scott, Donna Howell-Sickles, Lanford Monroe, Kathy Wipfler, Sherry Salari Sander, and Kathryn Mapes Turner.

Courtesy of the National Museum of Wildlife Art

Wyoming Women to Watch

Last year was the first that Wyoming was part of the National Museum of Women in the Arts’ roughly triennial Women to Watch exhibition series. The exhibition is a global survey of work by women artists and a collaboration between the National Museum of Women in the Arts and state-led committees. The late Wyoming-based arts advocate Lisa Claudy Fleischman led a group that was able to raise the funds needed to include Wyoming in the 2024 exhibit, which had the theme of “New Worlds.”

Wyoming women artists were invited to share their work with a selection committee, which included Jackson-based art consultant Shari Brownfield and Tammi Hanawalt, PhD, the curator of art at the National Museum of Wildlife Art. From this group, the committee selected five artists’ work to submit to the National Museum of Women in the Arts, which then picked one to be included in the exhibit.

The five Wyoming women artists presented to the National Museum of Women in the Arts were: Jennifer Rife (Cheyenne), Bronwyn Minton (Jackson), Leah Hardy (Laramie), Katy Ann Fox (Jackson), and Sarah Ortegnon High Walking (a member of the Eastern Shoshone tribe). High Walking’s piece—a painting capturing four different jingle dresses, each of which represents a season and that appears to move—was selected to be one of the 28 works in the exhibit, which was on display from April 14–August 11, 2024. “Even throughout history, there’s not a whole lot of women artists that are recognized,” High Walking told Wyoming Public Radio. “But the women that were recognized were very powerful artists. And so, it just means a lot to me.” JH