Read The

Current Issue

The Climbers Life

While “dirtbagging” looks very different today than its heyday in the 1950s and 60s, its spirit, albeit altered, is alive.

// By Molly Absolon

noun: dert•bag: A person who is committed to a given (usually extreme) lifestyle to the point of abandoning employment and other societal norms in order to pursue said lifestyle. Dirtbags can be distinguished from hippies by the fact that dirtbags have a specific reason for their living communally, and generally non-hygienically; dirtbags are seeking to spend all of their moments pursuing their lifestyle. The best examples of dirtbags … are the communities of climbers that can be found in any of the major climbing areas of North America.

—UrbanDictionary.com

I recently found myself behind a shiny new, fully outfitted Sprinter van that sported a sticker proudly proclaiming its driver to be a “dirtbag.”

Huh? To me, Sprinter vans, which range in price from $45,000—completely stripped down—to pretty much as much as you’re willing to spend (there are $300,000 Sprinters driving around Jackson Hole) and dirtbags are diametrically opposed. One connotes wealth, the other poverty, albeit voluntary poverty. And yet, my guess is that, at their core, vanlifers are the descendants of dirtbaggers, as they, too, are people who have opted out of a 9-to-5 lifestyle in order to pursue their dreams.

The first-known media reference to the term “dirtbag” dates to the trial of actress Claudine Longet, who was convicted of criminally negligent homicide in the 1970s. Her victim, professional skier Spider Sabich, called himself a dirtbag, according to a Climbinghouse.com article by Gabriel Grams. But Sabich wasn’t the originator of the concept. That honor undoubtedly goes to climbers, who as early as the late 1950s began dropping out of society’s rat race to climb full-time.

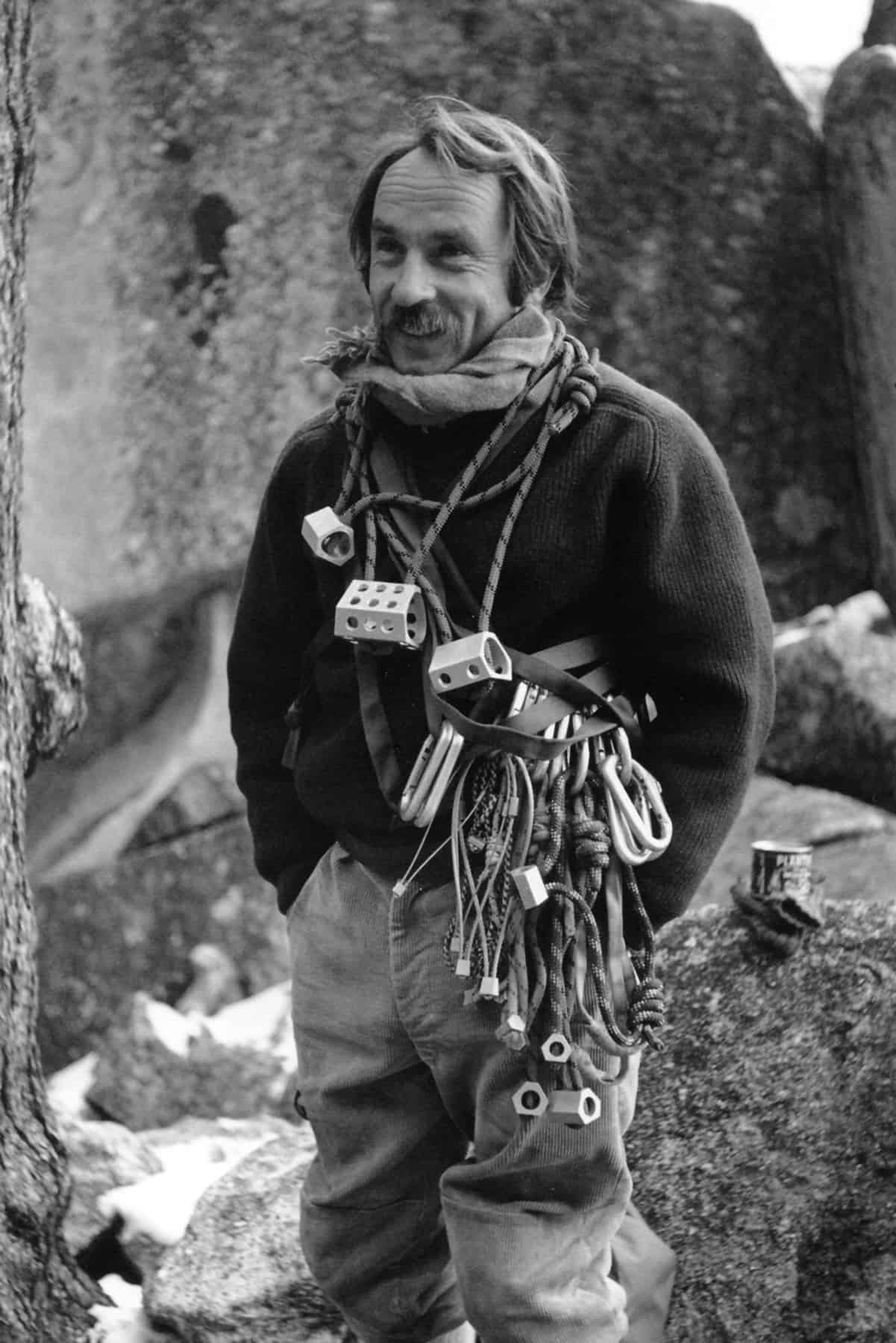

For many, the archetypal dirtbag is Yvon Chouinard, who, in 1973 founded Patagonia, Inc. Chouinard first came to the Tetons to climb in 1956, and he spent many summers camped in the Civilian Conservation Corps’ campground (the former bathhouse of which is today the headquarters of Exum Mountain Guides), the Tetons’ version of Yosemite National Park’s famed Camp IV. Chouinard described the vagabond lifestyle of the CCC camp in the introduction to Glenn Exum’s 1998 book Never a Bad Word, or a Twisted Rope: “The dirtbag climber’s life existed on the fringes of society, climbing hard and sleeping in an old CCC camp incinerator. A mainly oatmeal diet was supplemented with the occasional poached (not a cooking term) ‘fool’s hen,’ marmot, or porcupine. On special days there was spaghetti with a can of cat tuna from the dented can store in San Francisco.”

Chouinard was not alone. There were countless climbers foregoing college degrees, homes, and regular jobs. The late 1950s and 1960s could be called the Golden Age of dirtbagging. In part, this phenomenon may have been a reaction to World War II and the horrors of the Holocaust, the nuclear bomb, and the devastation of war. In the 1970s, it may have been in response to the Vietnam era and the rise of the hippie movement. Like dirtbags, hippies rejected established institutions and opposed social orthodoxy. Most lived very simply and didn’t hold regular jobs. But there were distinct differences. Hippies didn’t climb, and most climbers of the era didn’t really care about protesting the war. They just wanted to get on the rock.

Joe Kelsey, the author of Climbing and Hiking in the Wind River Range and an Exum guide for many years, says that as an Easterner who learned to climb in New York’s Shawangunks, the Tetons were “the magic realm” and the Grand the magnet. Kelsey was part of the infamous Gunks’ Vulgarians, a notorious group of hard-living, hard-climbing elite. He joined the influx of Vulgarians coming to the Tetons in 1964 and landed in the CCC camp during the height of its decadency.

“The park decided it was best to keep climbers away from tourists,” Kelsey says. “Probably because of the substance abuse, among other things. Well, the Vulgarians mixed with the California climbers there. … And the Vulgarians learned to use the Yosemite decimal [climbing] rating system, while the Yosemite climbers learned about drugs, sex, and rock and roll from the Vulgarians. Those famous Yosemite climbers were shy social misfits; they were way behind in terms of sex and drugs.”

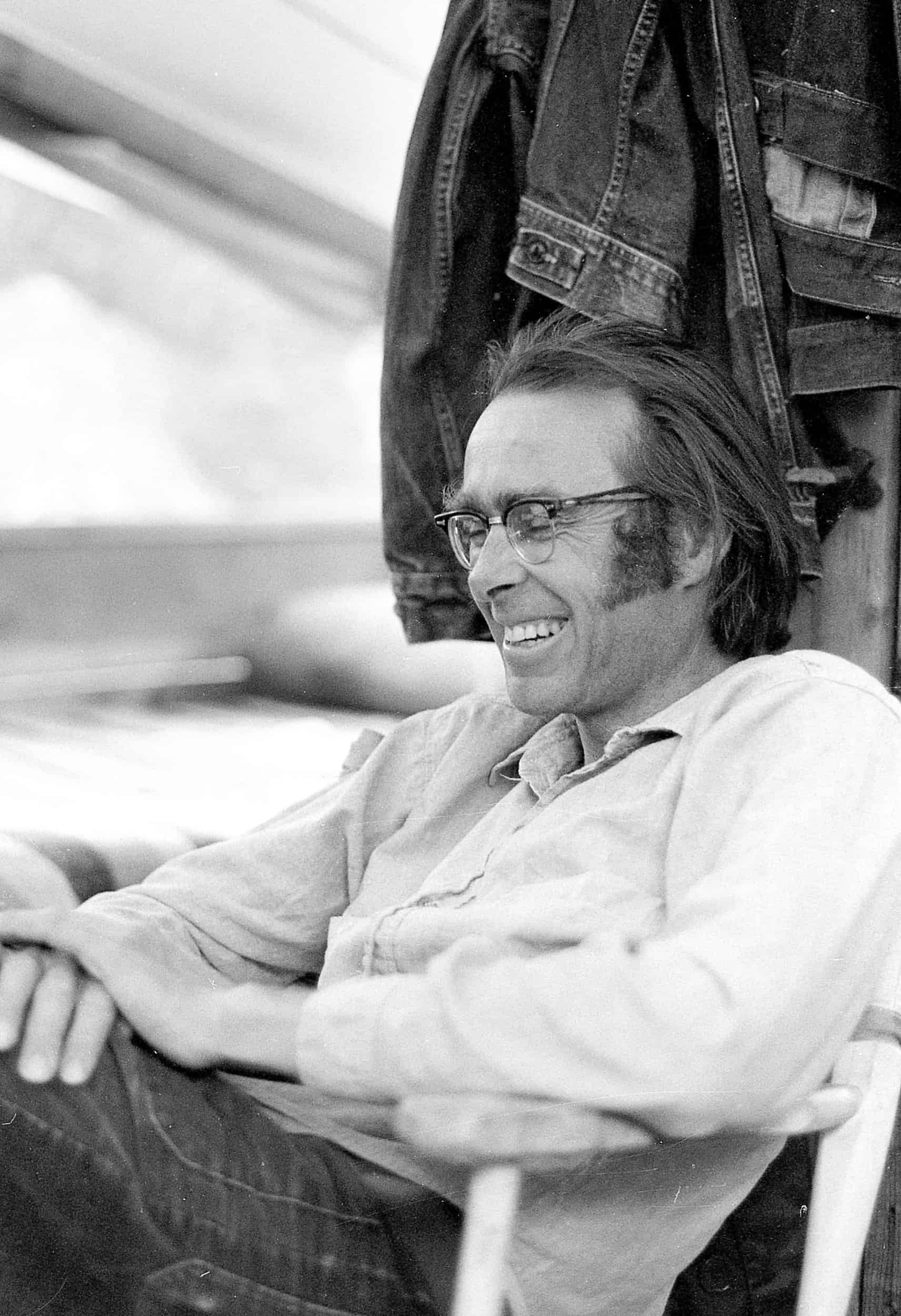

Another local legend, Bill Briggs (the first person to ski the Grand Teton, in 1971), was also hanging out in Jackson Hole and climbing at that time. He says he always associated climbing with singing, a much less decadent pasttime than what some other climbers were up to. “The Tetons were becoming the mecca for mountaineering in the United States,” Briggs says. “I thought music-making should be part of it. And so, in great desperation, I tried it at my camping spot under the new bridge at Moose. I provided a pot of half tea, half wine. Word got out, and it became popular. Too popular in fact. The park service shut it down and then opened the old CCC camp as a climber’s campground, agreeing music-making belonged in the park. The teapot eventually got replaced by Yvon [Chouinard]’s cauldron, and these gatherings became known as Teton Tea Parties.”

By 1965, as many as 150 people were gathering for Briggs’ Tea Parties, not all of them climbers. The CCC camp had become, according to Pete Sinclair, the author of We Aspired: The Last Innocent Americans, “a zoological garden displaying human specimens.” The Tea Parties attracted both climbers and people from town who were curious about what was going on out in the park.

Andy Carson, the former owner of Jackson Hole Mountain Guides, says he remembers hearing a story about a gun battle over women occurring at a Tea Party. Fortunately, he says, the participants were too drunk to shoot straight so no one was injured.

But the decadence was only one small part of dirtbagging. The real bond was climbing. These men and the occasional woman were putting up climbs at an increasingly difficult grade, and as the difficulty increased, climbers changed. “There’s something different about the new generation of climbers,” says Jane Gallie, who first came to Jackson in 1981 and has been managing the Exum office and guiding ever since. “They aren’t womanizers like they were in the old days. They are all such athletes. It doesn’t seem as if they do drugs or drink to excess the way they used to.”

Gallie grew up in Canada and was first introduced to the mountain scene in the Canadian Rockies where many of the guides were from Switzerland, which had a long, well-respected guiding tradition. The United States was slower to adopt that kind of professionalism. Glenn Exum refused to hire Yvon Chouinard as a guide because of his ratty appearance, not because he—like the majority of aspiring and actual climbing guides in the U.S. at that time—lacked any kind of accreditation from an outside governing body looking to establish basic norms for the climbing industry. Accreditation of guides didn’t start happening until 1979, when the American Guides Association was created (although the organization really didn’t become mainstream until the early 2000s).

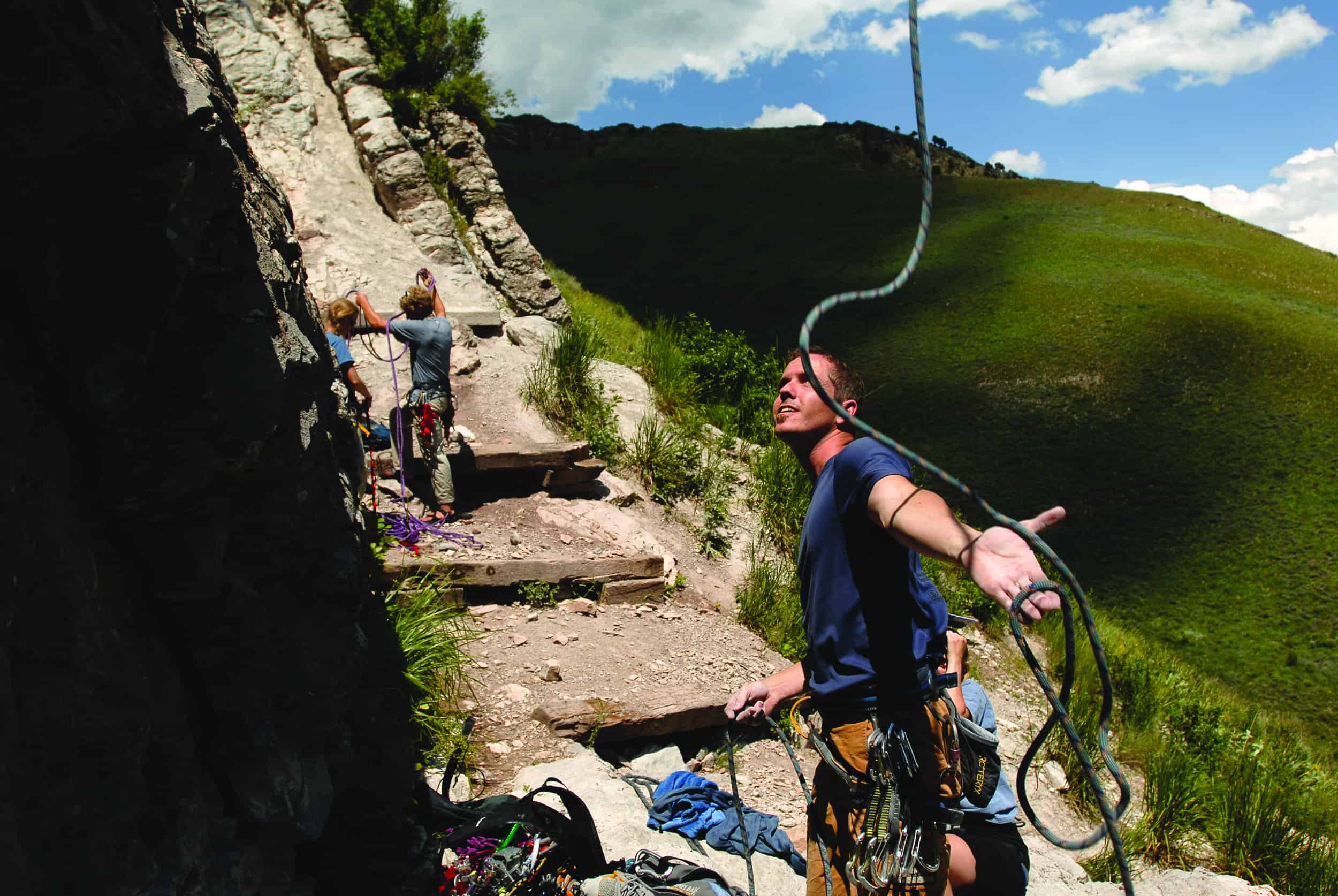

“I feel like my generation was kind of the first of Americans who could focus on making a full-time living as a mountain guide,” says Christian Santelices, who has been guiding since 1989 and works for Exum Guides as well as his own company, Aerial Boundaries. “I like to think that I had a dirtbag climbing lifestyle,” he says. “But I worked my butt off. I never took that path of fully checking out and living in my car, and I don’t know how many people actually did.

“I really look up to Yvon Chouinard and that era of climbers. … All their stories of living in Yosemite on very little are super romantic, but they worked as well, and look at what they accomplished. They started all these iconic companies—Patagonia, The North Face, Royal Robbins—but it took a tremendous amount of work and vision to do that. So, it’s not as if they didn’t work.”

Founder and board chair of the Teton Climbers Coalition, Christian Beckwith says when he co-founded The Alpinist magazine in 2002, he witnessed a shift among climbers toward more athleticism. Climbers were suddenly training like Olympians, and those who wanted to perform at elite levels couldn’t afford to live as decadently as their predecessors had. “Another element that’s changed is we have a much more affluent culture,” he says. “Everyone these days is tooling around in $150,000 vehicles. How did that happen?”

“I think some people are still living the dirtbag lifestyle,” says Nat Patridge, co-owner of Exum Guides. “Say, for example, Alex Honnold before the movie Free Solo was made. But at the same time, I wouldn’t categorize him the way I would those guys back in Chouinard’s day. It doesn’t seem as desperate. Today’s dirtbags are focused athletes living in a van, different from the bygone era of getting scraps of pizza out of the garbage at Curry Village in Yosemite.

“That said, it is still a deviant life, even if you are living relatively comfortably in a van. You still don’t have running water, it’s still inconvenient. But I do think it’s possible to live that way if you are creative and have knowledge of public lands and an occasional place to shower.”

Skills for Today’s Dirtbag Wannabes

(adopted from ridgemontoutfitters.com)

• Wear used and hand-me-down clothes. Look for free boxes, peruse brown-bag sales, and shop at Goodwill (not Jackson’s high-end consignment shops). Don’t worry about size, smell, or style; the key factor is price. Cheap is good, free is better.

• Eat free food. In Jackson, check out Food Rescue, and in Teton Valley, look for Food For Good. Both organizations give away perfectly good food saved from the landfill. Sometimes you also can find leftovers at hostels or in campground bear boxes to supplement your diet. Or shop the clearance racks. Again, cheap is good, free is better.

• Be dirty. Be willing to forego showers and freshly washed hair. The best way to get clean as a dirtbagger? Jump in a lake and scrub (sans soap), or get to know where you can find inexpensive showers—recreation centers, truck stops, and RV-campgrounds are all options.

• Use public libraries for WiFi or free computer time.

• Know your public lands and where you can find free and legal camping. Don’t arrive late and expect to find a site. There are a lot of us out there in vans these days.

The Dark Side of the Dirtbag Lifestyle

Society has romanticized the idea of the dirtbagger. It’s about self-actualization. It’s the pursuit of adventure over predictability. It’s the pure spirit of living in the moment. There are elements of truth in these ideals, but there is also the failure to recognize that it takes privilege to opt for voluntary poverty—privilege that is not accessible to many people of color.

According to a 2020 article on the impartial German—but translated in 32 languages—news site DW.com entitled “Racism Also an Issue in Sport Climbing,” Duane Raleigh, the editor and publisher of Rock and Ice magazine resigned from his post and apologized for his past behavior. “We were young and could climb and enjoy risks because we had freedoms that nonwhite America does not have,” he said. “We were part of a culture that I

regret. White privilege let our ‘fraternity’ exist, and we could be inappropriate, and do just about anything without consequence.”

That inappropriate behavior and attitude was certainly dominant in dirtbagging’s heyday, and you can excuse some of it by considering the times. But no longer. Climbers in general have cleaned up their acts, but glorifying an outdated term is still common and potentially offensive.

Dirtbag also has negative connotations when applied to people of color. A badge of honor for white climbers, it’s a word that brings up associations of oppression for many Blacks. The word may be here for a while, but climbers might want to consider what they are saying when they toss it around

casually from the seat of their Sprinter van. JH