Read The

Current Issue

Soak for Health

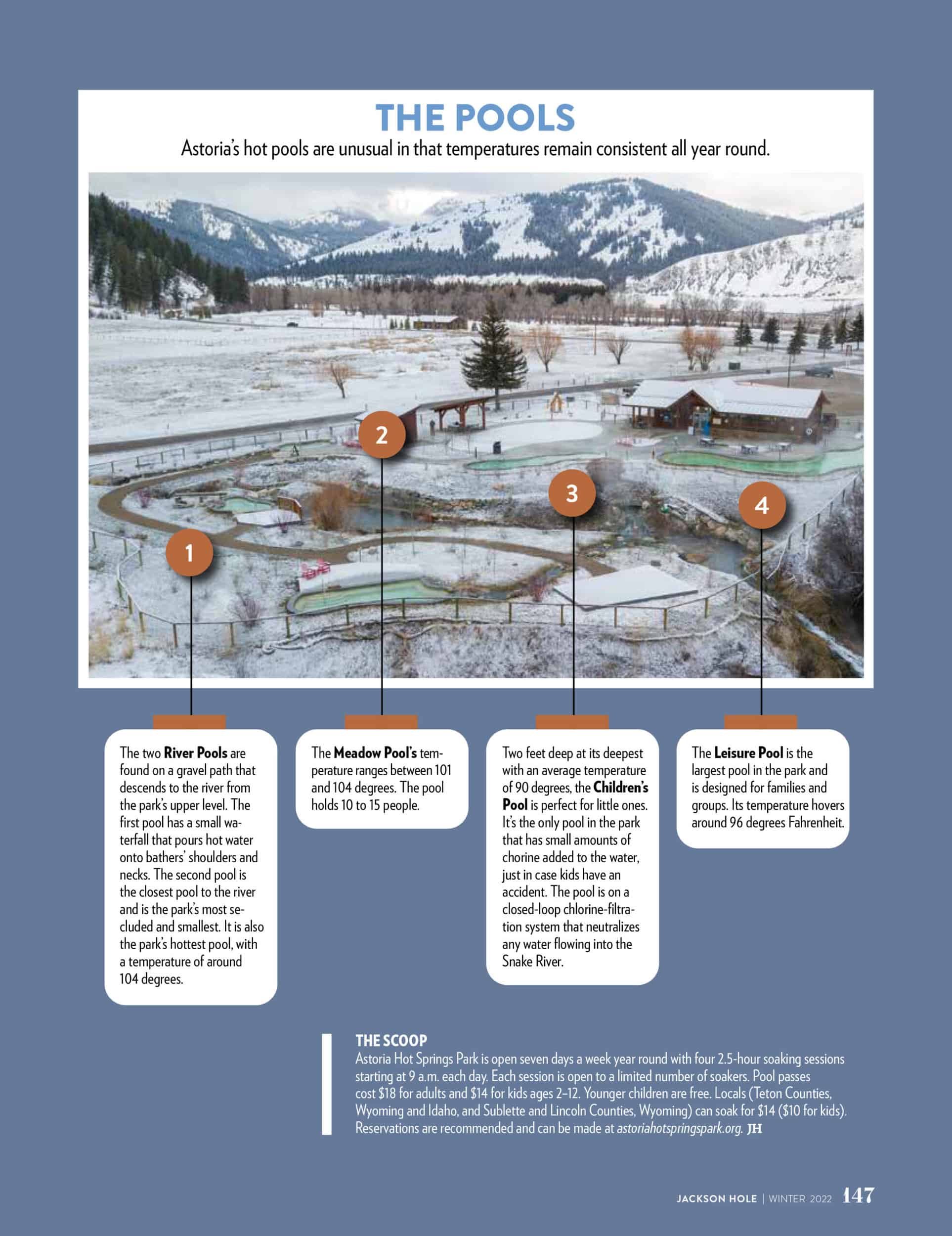

Astoria Hot Springs Park offers mineral hot springs.

// By Molly Absolon // Photography by ryan dorgan

There’s nothing quite like stepping into the soothing mineral waters of a hot spring on a cold, snowy day. Steam rises up from the pools, creating a diaphanous veil of mist that hides the landscapes and hints at mystery. Warm water eases away tension and stress, and the sound of gurgling water adds to an overall sense of peace and calm.

Natural hot springs have had their avid fans for centuries. People seek hot springs out for healing, relaxing, and as a place to socialize with friends, but for years, Jackson locals and visitors have had to travel to enjoy a good soak. Now, after a 20-year hiatus, Jackson Hole once again has its own public hot springs: Astoria Hot Springs Park. It’s a fun place to relax and unwind, and a nice alternative from the valley’s action-packed lifestyle, especially on a frigid winter day when nothing feels better than submerging oneself in hot water.

Astoria’s pools stretch above the banks of the Snake River and are surrounded by open hillsides and meadows. Even in the winter, eagles often soar overhead and elk are commonly seen browsing on the south-facing slopes above the park. The pools are fed by natural hot springs that contain magnesium, sulfur, calcium, potassium, sodium, and chloride—minerals said to reduce inflammation, sooth skin conditions, and increase oxygen levels in blood. People have sought these healing properties at Astoria for as long as they have lived in and traveled through the area, but the public pool that was popular for the last half of the 20th century was closed and razed in 1999. Twenty-one years later, in September 2020, Astoria Hot Springs Park was rebuilt and reopened to soakers.

Named for the Astorians, a group of fur trappers who crossed what is now the western United States in 1811 to establish a trading post on the Columbia River, these hot springs were used by indigenous groups for hundreds of years before mountain men showed up on the scene. Few details about this early use remain, but it is believed that all of the 23 Native American tribes known to have been in the Jackson Hole area camped at the hot springs and used them for ceremonial purposes. Astoria Park Conservancy’s executive director, Paige Curry, dreams of someday sponsoring an archeological dig on the park’s 100-acre property to learn more about its rich human history.

Astoria Hot Springs is truly a wonderful place to sit and contemplate nature and an experience that our whole family loves to relish. I am so happy to have it back.”

—Juniper Lopez Troxel

In the early the 1900s, prospector Johnny Counts lived in a small cabin here, where he panned for gold (on a claim that wasn’t particularly rich; Counts averaged about $1 a day in gold for his work). Curry says she’s been told that people—especially those who were ill and seeking healing benefits—would float down the Snake River from Jackson to soak in natural hot pools along the river that were called Counts’s Hot Springs. Counts’s cabin still stands near the new hot springs, but it is closed to visitors and now used for storage. A grave near the hot springs is reputed to belong to Counts, but Curry says that’s another mystery an archeological examination could help unravel.

Astoria’s ownership changed hands a few times after Counts, and, in 1961, Robert Porter, who was part of the Gill family, captured water flowing from the hot springs in a 40-by-80-foot pool and opened it to the public. Astoria was the only public swimming pool of any kind in the area, and it became a beloved hangout spot for locals of all ages. It also attracted visitors to the area. At one point, the Porter/Gill family’s operation included a tourist village with RV and tent camping, guided hunting and fishing trips, and a snack bar where you could buy hot dogs, hamburgers, and ice cream. The Gill family managed this rustic, no-frills park until 1999, when it became clear that repairs required to keep the pool open exceeded revenues, so they closed down and sold the operation.

The property was bought and almost immediately sold again to the Canyon Club, which became the Snake River Sporting Club. The Sporting Club’s plans to develop 26 single-family homes, 44 condominium units, and a four-story luxury lodge and spa near the hot springs were approved by the county in the early 2000s. But these plans were significantly altered and postponed by the Great Recession, giving conservation groups and locals a chance to protect the hot springs.

In 2012 the Trust for Public Land, a national nonprofit dedicated to creating parks and protecting land, came forward with a plan to work with the Snake River Sporting Club ownership group to figure out a way the hot springs land could be saved from development and made public. A community fundraising campaign garnered $6 million to purchase 100 acres on the banks of the Snake River that included the hot springs and important riparian areas. In exchange, the development rights originally associated with the hot springs site were transferred to less-ecologically sensitive land owned by the Snake River Sporting Club farther downstream. Astoria Hot Springs Park opened in 2020. That same year, the Trust for Public Land transferred the property to the Astoria Park Conservancy, a nonprofit established to support the park.

“I have a faint memory of the old Astoria from the ’90s,” says 26-year valley resident Juniper Lopez Troxel. “When I heard they were reopening, I started counting the days and following closely all the work in progress on Instagram. Since it reopened, I have celebrated kids’ birthdays, anniversaries, Mother’s Day, date nights, girl gatherings, and just general quality time with my family there. Astoria Hot Springs is truly a wonderful place to sit and contemplate nature and an experience that our whole family loves to relish. I am so happy to have it back.”

The Astorians after which these hot springs are named briefly considered abandoning their horses near here and floating down the Snake River in dugout canoes. Local Shoshone dissuaded them through sign language, communicating that there were dangerous rapids downstream. Subsequent European visitors to this area called the Snake River the “Mad River” because of this whitewater.