Read The

Current Issue

Wild, Again

Animals that escaped from their outdoors exhibit more than a half century ago led to the modern day Jackson bison herd—Wyoming’s only herd of wild bison outside of Yellowstone National Park.

// By Mike Koshmrl

Traffic slows, then eases to a standstill past where the Buffalo Fork of the SnakeRiver gives way to a sweep of grassy pastureland. Off to the west, the sawtooth of the Tetons. The eastern skyline is cut by triangular Mount Leidy rising above a rolling sea of conifer forest. But the scenic vistas play second fiddle to the center and cause of the congestion on U.S. 191/26.

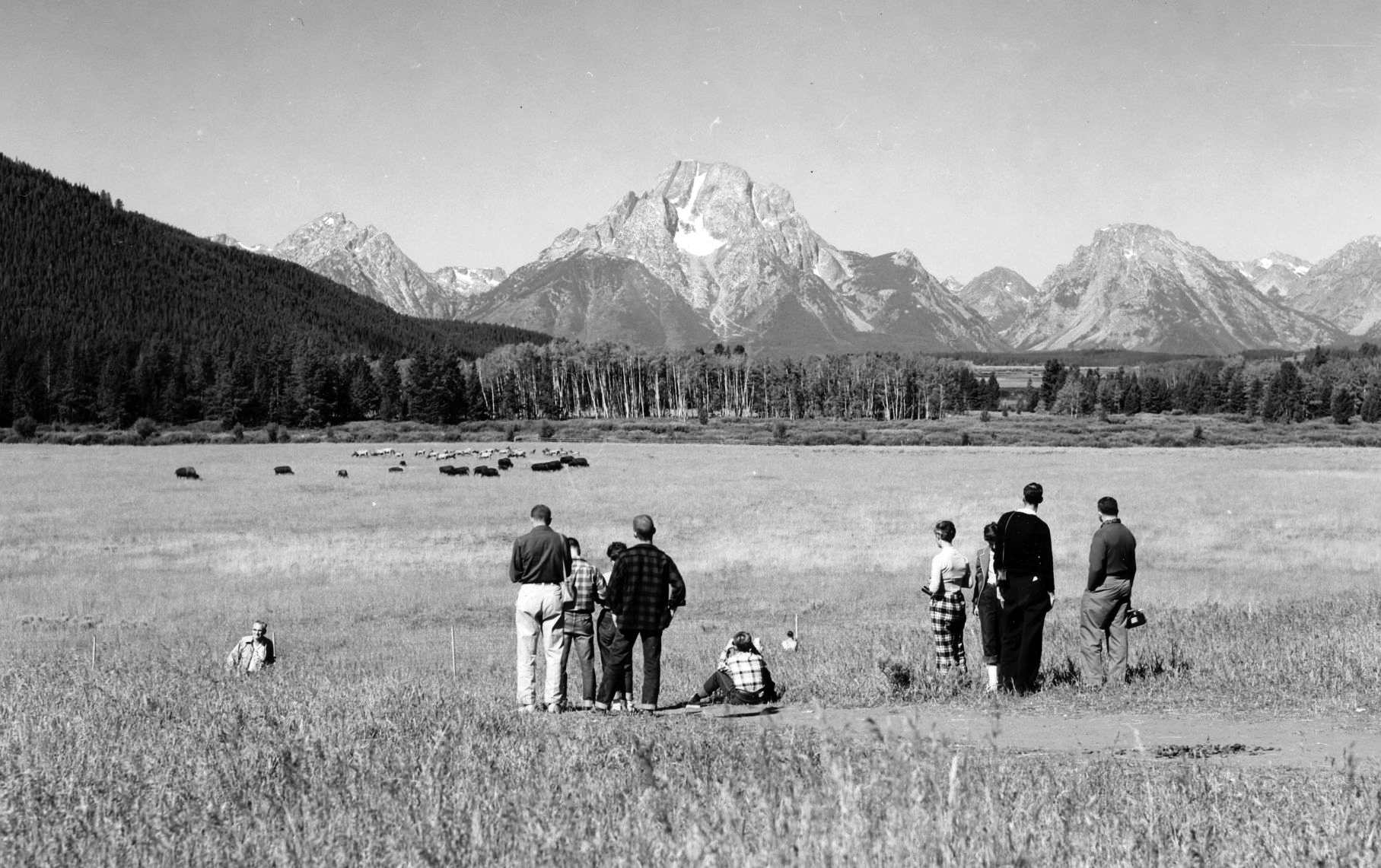

It’s a heap of bison. A herd grazes the flats where the old Elk Ranch ran cattle in the early 1900s. And the tourists passing by, many of whom have never seen North America’s largest mammal in the wild, are struck with awe by the bevy of wooly, lumbering animals. With cameras and smartphones in hand—to capture memories of a species that was infamously eradicated from virtually all of its range—they scamper across the highway.

This is a scenario that plays out in Grand Teton National Park on repeat every summer. But it wasn’t always the case. In Jackson Hole, too, bison were eliminated—absent from the landscape for an entire century. Today, there’s a free-ranging herd—a noted conservation success—that is understandably overshadowed by the story of bison in Yellowstone National Park, where the species was famously brought back from the brink of extinction in the early 1900s at the Lamar Buffalo Ranch. Still, Jackson Hole residents like senior National Elk Refuge biologist Eric Cole are well aware that the 500 or so bison that call the valley home are an extraordinary resource for the ecosystem and community. “The Jackson bison herd has gotten very little attention given its relative importance,” Cole says. “I definitely appreciate having them on the landscape because it’s such a rarity in North America.”

The return of Bison bison bison to Jackson Hole came about because of a historic getaway. Imported from Yellowstone in the 1940s to endure captive lives in a fenced pen, Jackson Hole’s bison escaped, survived, proliferated, and went on to become one of only herds of wild bison allowed to exist on a Western landscape that’s now dominated by another bovid: domestic cattle. The bison grazing today to the delight of tourists at Elk Ranch Flats descend from animals that were essentially props. At the time, Wyoming Governor Lester Hunt was dissatisfied that sometimes the only animals tourists would see on their drives through Jackson Hole were cattle. Grand Teton National Park was much smaller then—confined mostly to the Tetons themselves—and Hunt convinced Laurance Rockefeller to finance a wildlife exhibit near the Snake River’s Oxbow Bend for bison, elk, antelope, moose, and deer. But the enclosure, dubbed the Jackson Hole Wildlife Park, quickly failed, partly because of a lack of cooperation from its animal occupants, wrote historian and Grand Teton National Park scholar Robert Righter.

“The Jackson bison herd has gotten very little attention given its relative importance. I definitely appreciate having them on the landscape because it’s such a rarity in North America.”

Eric Cole, National Elk Refuge biologist

In the past, Wyoming Game and Fish Department employees used snowmobiles (just out of the picture) to haze bison away from private property near Triangle X Ranch in Grand Teton National Park.

Bison would escape “several times annually,” according to a 1996 interagency management plan for the Jackson bison herd. They’d get rounded up and returned. When Grand Teton National Park expanded its boundaries in 1950, the National Park Service reluctantly inherited the wildlife park. Righter likened the failed exhibit to an “unwanted stepchild.” By 1969, park officials stopped attempting to round up the escapees. Jackson Hole, for the first time in nearly a century, became the domain of free-ranging bison (with the exception of when three Yellowstone bison wandered south into Jackson Hole in 1945).

In the early years, free roaming the valley, the herd stayed very small, averaging just a dozen or so animals. That began to change in 1975, when bison discovered where to go for a winter’s worth of free meals. “Once these bison found the National Elk Refuge, the population really started to reproduce at a high level,” says Doug Brimeyer, who arrived in Jackson Hole in the 1990s for a Wyoming Game and Fish biologist gig. “We saw that growth trajectory really change.” Eventually, dozens became hundreds and then a thousand-plus bison. Around that time, the Wyoming Game and Fish Commission created bison regulations and classified the species as wildlife so long as they were not privately owned and did dwell within a defined area that now includes Teton, Lincoln, and Sublette Counties. Elsewhere in Wyoming, with the exception of the unoccupied Absaroka herd unit east of Yellowstone, bison aren’t classified as wildlife, but “privately owned or bison running at large.” (See sidebar, “A Political Animal,” p. 128)

At first, recreational hunting was not an especially effective tool for keeping Jackson herd numbers in check, Brimeyer says. It was partly because the Fund for Animals sued, successfully keeping bison hunting off the National Elk Refuge from 1998 to 2006. “Bison are extremely sensitive to hunting pressure,” says Brimeyer, now the deputy chief of wildlife for all of Wyoming Game and Fish. “They figured out pretty quickly, between 1998 and 2006, that the refuge was the place to go.”

Ryan Dorgan

But in 2007, the no-hunting sanctuary went away. Grand Teton National Park and the National Elk Refuge completed a new management plan, with a goal to trim bison numbers from 1,200 down to 500 animals. This lifted the court-ordered hunting prohibition on the refuge. For a time, the higher bison numbers complicated wildlife management in Jackson Hole. At up to 2,000 pounds, infamously testy at times, and at the top of the wildlife hierarchy, bison aren’t always easy to live with. Even though Teton County is 97 percent federal land, bison and other wildlife are often drawn to the lowest-elevation areas, which tend to be privately owned. Bison were notorious fence breakers, Brimeyer says, and destructive when they got into subdivisions. They’ve been hazed from places like Jackson Hole Golf and Tennis and away from ranchers’ haylines, where they’d gained a reputation for goring horses. Once, Grand Teton National Park closed down the highway in the dead of winter so snowmobile-mounted wardens and biologists could herd snowbound bison down the plowed roadway south toward the refuge and away from ranchland.

Throughout the 2010s, the Jackson bison herd was hunted down hard—and it wasn’t always pretty. Word often spread when a group crossed the Gros Ventre River from GTNP and onto the National Elk Refuge where they were fair game, and it could be a shooting gallery. Even if it was tough to watch, the tactic worked: numbers dropped steadily toward 500. Once tag numbers dropped, the hunts became less ugly. Brimeyer, who once hunted a Jackson Hole bison, reported his own experience was “very ideal” and that the animals he pursued were wary. Today, the Jackson bison herd has reached some sort of equilibrium. Numbers have stagnated slightly below the 500 animal objective for the past five years. Conflicts with golf courses and on private ranches are less frequent. “Having a lower number of bison in the population has certainly helped us out,” Brimeyer says.

Still, it’s not the ideal of a wild bison herd in the eyes of everybody. As it functions today, just about every bison in the Jackson herd survives the winter lapping up alfalfa pellets on the National Elk Refuge, which is fenced on two sides. The spread of diseases is one knock against feeding, but opponents have rallied against the anachronistic wildlife-management tactic for a host of additional reasons for decades. “It’s just an artificial attempt to sustain populations that don’t meet the definition of wild,” says Darrell Geist, a habitat coordinator and longtime activist for the Buffalo Field Campaign, based in West Yellowstone, Montana. In Geist’s view, Jackson Hole’s isolated wild bison population is “seriously deficient” and could be genetically challenged in the long run.

Yet, it’s plausible to think that the Jackson bison herd will shrink even more in the foreseeable future. The reason is that the National Elk Refuge is redoing its management plan, and feeding could be scaled back or altogether phased out. That outcome is still speculative, but it’s entirely possible, and it’s a scenario that would change the bison-management equation significantly. “The supplemental feeding program has mitigated a lot of the potential problems from having bison,” says Cole, the National Elk Refuge biologist. “If supplemental feeding is scaled back, we’ll be in uncharted waters in terms of the potential for bison to move to areas they haven’t in the past.” In winter, that could mean bison by Jackson Hole Airport—or in somebody’s backyard. Geist’s hope is that federal and state wildlife managers take the long view and plan smartly to chart the next chapter of the Jackson bison herd. “We need to figure out a way to restore habitat and, probably more importantly, restore connectivity between populations,” he says. “Start acquiring habitat for those bison. If you really want them to have a viable future, they’re going to need more habitat and range.”

A push for wild bison on the Wind River Indian Reservation

Eastern Shoshone Tribal member Jason Baldes has two major goals for bison conservation on the Wind River Indian Reservation, which he calls home: One, Baldes wants to bring back the buffalo—an effort that’s been slowly underway since 2016. Second, he wants to see those bison be declared as a wildlife species under the tribal game code. “It’s a paradigm shift, recognizing buffalo as a wildlife species and allowing them to exist on the landscape,” says Baldes, who leads the tribal buffalo program for the National Wildlife Federation.

Even on the Wind River Indian Reservation—a wild landscape the size of Yellowstone National Park—cattle are still considered king. “Like other places in the West, cattle were prioritized when reservations were opened up for homesteading,” Baldes says. “Colonization and assimilation was always the goal, and a real result of that is that cattle were prioritized on an Indian reservation.” That’s the case even though the Shoshone were buffalo people. They called themselves the Guchundeka, the “buffalo eaters.” “But we haven’t been able to eat buffalo for 140 years,” Baldes says. “There’s a hope that one day we can feed young people [buffalo] in our school lunch program.”

Cattle ranching Wind River tribal members haven’t met Baldes’s bison-restoration ambitions with open arms. “The tribal ranchers are concerned about buffalo because they think we’re taking all of the range units out from cattle production,” he says. “The idea isn’t to run anybody out of business or take their livelihood, but to reassess the history and reprioritize in a more holistic way. What is most beneficial for our tribal communities? The cattle, they benefit the individual. These buffalo, they benefit everybody.”

Although it’s come slowly, there has been progress. Baldes is raising funds, buying lands to graze and grow the Wind River herd, and lobbying his people to reembrace the buffalo.

A Political Animal

In 2016, the American bison was declared the national mammal of the United States. A century and a half earlier, however, white settlers homesteading the same nation drove bison to the brink of extinction by slaughtering the shaggy brown beasts by the millions. “When the plains bison was represented by 50, 60, 70 million animals, it was the greatest assemblage of mammalian biomass the world had ever produced,” says Mike Phillips, director of the Turner Endangered Species Fund. “Think about that for a moment. We took the greatest assemblage of a terrestrial mammal in all of creation and, in a few short decades, drove it nearly extinct.”

While the United States’ other wildlife emblem, the bald eagle, recovered from its own flirtation with extinction, bison have never recovered to become commonplace and widespread in the wild. Although there are approximately a half-million bison that exist on the planet today, the vast majority are fenced bison-cattle hybrids commercially raised for meat. The International Union for Conservation of Nature considers only 20 bison herds to be large and free-ranging enough to be “primarily subjected to the forces of natural selection.” By this standard, there are less than 19,000 wild bison alive today—a tiny fraction of a percent of what was.

The largest of these herds lives in the same landscape where the species staged a comeback: Yellowstone National Park. In the midst of a planning process for Yellowstone’s 6,000-animal bison herd, the National Park Service is examining three options: 1) a status quo approach to managing bison; 2) an option that would allow for a larger population that would prioritize tribal hunting; 3) managing bison like any other wildlife.

It’s likely that whatever Yellowstone does, the park will get hammered by criticism from both sides. The state of Montana and the state’s livestock lobby, fearing the spread of brucellosis, a transmissible disease that causes bovids to abort their first calf, has consistently opposed giving bison the right to roam outside of Yellowstone. Meanwhile, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is in the process of determining whether bison in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem ought to be protected under the Endangered Species Act. A decision on whether that will occur was overdue when Jackson Hole magazine went to press, but the federal agency has already signaled that “substantial scientific information” indicating that listing the Yellowstone bison under the ESA “may be warranted.” JH