Read The

Current Issue

Bishish’s Enclosure

Did Native Americans stand on the summit of the Grand Teton centuries before the first party of white men?

//By David Gonzales

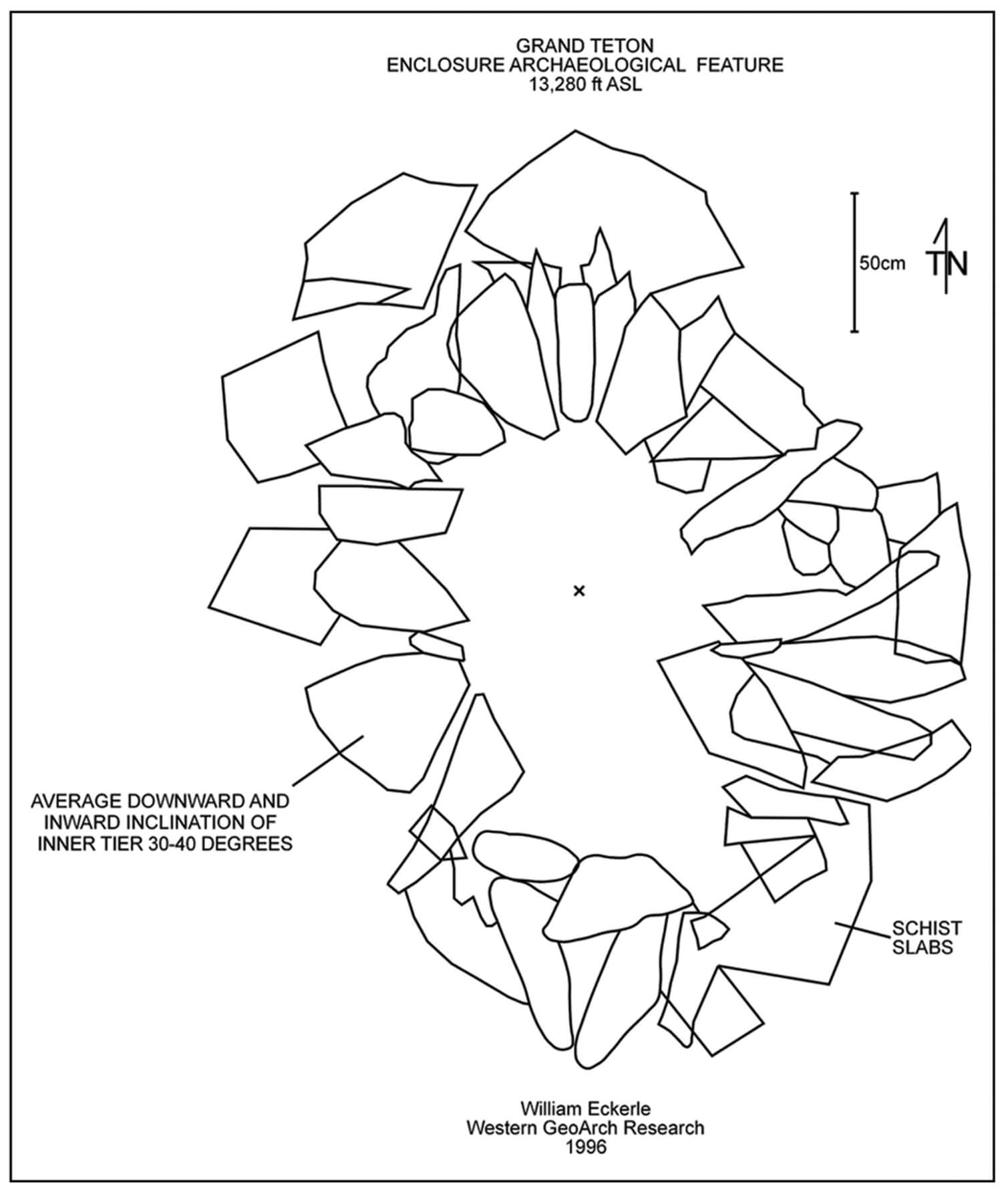

Near the summit of the Grand Teton, atop a rocky spur that forms the Grand’s west shoulder, is the most striking archaeological site in Grand Teton National Park. It’s a ring of sharp granite shards, each as large as a flat-screen TV, placed side-by-side to form a waist-high enclosure just large enough for one person to stretch out and lie in wait for game, or a sign.

The Crow, or Apsáalooke, people call these prehistoric rock structures “fasting beds,” and they’re scattered across traditional Crow lands in present-day Wyoming and Montana. A Crow seeking guidance or solace would climb alone to a remote, exposed spot on a bluff or ridge, construct a windbreak, and then strip naked before fasting and praying for four days, hoping for a guardian spirit to contact and counsel him.

The first white explorers to stumble across the site were utterly puzzled by the Enclosure, as both the structure and its rocky spire are now called. These were Nathaniel Langford and James Stevenson, two members of the Hayden Survey of 1871, the second U.S. government expedition to map and explore the Yellowstone region. As the expedition journeyed along the western slope of the Tetons, Langford, Stevenson, and a few others set off to scale the Grand.

The group bushwhacked and scrambled to the saddle between the Grand and Middle Teton, then Langford and Stevenson proceeded cautiously to the top of the Enclosure, where they were stunned to discover its crown of standing stones. As Langford would write in his ensuing article in the June 1873 issue of Scribner’s magazine: On one of the adjoining buttresses, which was but a little lower than the very summit, we found a curiosity in the shape of granite slabs piled up on end, in circular form, 6 feet diameter, the space filled with disintegrating granite … This was probably done hundreds of years ago, for hundreds of years must have been required to fill this space with granite fragments as small as these.

This passage describes the site just as it looks today.

Leaving the Enclosure, Langford and Stevenson proceeded to have one of the most controversial climbing days in Grand Teton history, which is worth discussing before returning to the possible origins of the Enclosure.

What the duo did was claim to clamber over sheets of ice to summit the Grand, with no evidence to show for it, save their questionable word. In his Scribner’s article, Langford’s description of the terrain above the Enclosure is wildly inaccurate: “Exposure to the winds kept it free from snow and ice, and its bald, denuded head was worn smooth by the elemental warfare waged around it.”

In this author’s opinion, the words “bald, denuded head, worn smooth” betray Langford and Stevenson’s failed mission and resultant fraud, as the top of the mountain is an immense pile of jagged rocks with few places to sit or stand.

The world took Langford at his word until 1898, when Billy Owen, the Wyoming State Auditor, organized a successful ascent of the Grand with Franklin Spalding, an episcopal minister who led the party through the technical terrain; Frank Petersen; and John Shive. As soon as they descended, Owen claimed the first ascent, as he’d already doubted Langford’s claim, and saw no cairn at the top, or any other sign of a previous ascent.

The controversy continues today, with some armchair mountaineers still believing Langford and Stevenson were successful, though most historians ascribe the Grand’s first undisputed ascent to Owen, grudgingly. Owen was so obsessed with claiming the first ascent that he cajoled the Wyoming legislature into officially proclaiming his party the first, then had a bronze plaque created saying so, and in 1929 convinced Grand Teton National Park’s first rangers to install it on the summit of the Grand. It remained bolted to a summit slab until 1977, when it was mysteriously pried off and never seen again.

Owen’s claim to the Grand’s first ascent would seem settled. But is it? When Langford announced his and Stevenson’s feat, he wrote in Scribner’s, “We felt that we had achieved a victory, and that it was something for ourselves to know—a solitary satisfaction—that we were the first white men who had ever stood upon the spot we then occupied.” For Langford to say “the first white men” was to acknowledge the probability, if not the certainty, that Indigenous climbers had ascended the Grand first, though this probability is rarely mentioned today.

Back to the Enclosure and its similarity to other Crow/Apsáalooke fasting beds. Before he passed away in 2020, Apsáalooke storyteller Grant Bulltail related that the Teton Mountain Range is known to his people as “Bishish’s Father,” because a young Crow named Bishish once fasted high in the Tetons, where a shining being appeared and urged him to voyage south to find horses for his people. Bishish did so, returning seven years later with fast Spanish ponies, giving the Crow an upper hand in hunting and warfare.

If you take the Bishish story literally, and assume he built the Enclosure, the story holds together. According to various Crow traditions, they first gained horses in the early 1700s, which would jibe with what Langford said in Scribner’s: “It could not have been constructed less than a century ago, and it is not improbable that its age may reach back for many centuries.”

Even if Bishish were a myth, the question remains whether the person who built the Enclosure might have climbed the Grand Teton. Wouldn’t the person with the energy and audacity to create a fasting bed in this most extreme setting think nothing of making a side trip to the summit? While guiding Owen and the others, Spalding had no trouble finding the narrow, airy ledges that lead to the upper mountain. Someone who’d lived his whole life outside, who could fast atop a 13,280-foot spire for four days, would have found and navigated those ledges just as easily.

Shoshone historian Laine Thom contends that Native Americans regard summits differently than whites and don’t feel the need to conquer. But if you’re choosing the 13,280-foot shoulder of the Grand Teton as your fasting bed, you’re clearly the type that has to do things more dramatically and strenuously than anyone else. Of course, this is all speculative, but there’s no harm in reserving a sliver of a chance that a Crow named Bishish created the Enclosure and climbed the Grand before bringing horses to his people. JH