Read The

Current Issue

Shacks on Racks

Can moving —rather than demolishing— old homes help with Jackson Hole’s housing crisis?

// By Sue Muncaster

David Newby, the owner of Great Divide Earthworks, his wife, Anne, and daughters Kayla (13) and Victoria (10) lived in Afton, Wyoming, when Newby got a phone call they were all happy about. An old workmate wanted to know if Newby, who had been commuting the almost 70 miles (one-way) between Afton and Jackson for 18 years, wanted a new house. And, if he did, could he move the 1,250-square-foot home from West Gros Ventre Butte, between Jackson and Wilson, to wherever he and his family wanted to live in it?

The Newby family’s Afton home was cramped, and the girls shared a bedroom. Luckily, the family owned two five-acre empty lots in Etna (35 minutes closer to Jackson). Newby submitted a route plan to the Wyoming Department of Transportation less than a day after he got his former colleague’s phone call. Shortly after, Anne and the girls were walking through the house, which had been built in the 1980s, on West Gros Ventre Butte, picking out their bedrooms and figuring out where to put furniture.

Three weeks later, the 29-foot-wide home was moved, albeit not easily. Shacks on Racks, which facilitated the home’s relocation, says it was their “most technical move to date” because of the steep, tight switchbacks on the butte. The home, placed on a foundation with a basement, now sits in Etna surrounded by enough land to store Newby’s business equipment and to raise livestock.

Not willing to wait for slow-moving businesses, nonprofits, and government agencies to address Jackson’s housing crisis, 39-year-old Esther Judge-Lennox started Shacks on Racks in 2018. Her mission is to help working families find affordable homes, counter wasteful habits by promoting the reuse of suitable materials, and stand up to the wrecking ball of progress by preserving historic homes and the legacies of the people who built and lived in them.

“I desperately wanted to be here. I was skimping and was frustrated enough to do something about it.”

—Esther Judge-Lennox

Along with one full-time employee, Ryan Dorgan, Judge-Lennox scours Teton County for pending demolitions and works to connect homeowners planning to redevelop their property with families in need of housing. Most structures leave Teton County, Wyoming, for Teton County, Idaho and Lincoln and Sublette Counties in Wyoming; Land-development regulations are less strict in these areas than in Teton County, Wyoming. With help from partners in the architectural, engineering, and structural building-moving worlds, Shacks on Racks decides whether moving a soon-to-be-demolished building is possible. The receiver pays the cost of relocation, and Shacks works to convince developers to donate part of their dump budget to relocate the structure.

As of January 2023, Shacks on Racks has saved 21 structures from demolition and diverted 1,205,150 pounds of garbage from the landfill. Developers have contributed a combined $193,050 of their dump budgets to help relocate homes.

Shacks on Racks came about organically, inspired by Judge-Lennox’s own housing crisis. After she and her husband, Philip, built a small house, they found they could no longer afford the mortgage. “Then we found out our neighbor’s house was being demolished and going to the trash. It blew my mind,” says Judge-Lennox. “I desperately wanted to be here. I was skimping and was frustrated enough to do something about it.” She and Philip found a 1940s craftsman-style cabin in Jackson that was about to be demolished. They paid $12,000 to move it onto their lot in Hoback, which was zoned for two homes. Thanks to the rental income this relocated home generates for them, the couple can now afford their own mortgage.

Judge-Lennox didn’t dream up moving homes and Shacks on Racks out of the blue. In 1998, as a young girl, she stood on a bridge over I-15 near Dillion, Montana, and watched the rundown “Roe Mansion” ride down the interstate. A gift from media mogul Ted Turner’s Red Rock Ranch, the restored historic Roe Mansion is now the administration building on the University of Western Montana campus.

In the words of Jackson Town Council member Jonathan Schecter, Teton County, Wyoming, is the “richest county in the richest country in the history of the world.” As a tax-friendly haven with spectacular scenery and world-class amenities, Jackson Hole continues to attract new homeowners with high salaries and investment income who can work remotely. In December of 2022, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis reported that Teton County once again led the nation in per capita income, and that this figure had experienced an astounding one-year jump of 44 percent (which equaled $97,404). In 2021, the per capita income of Teton County was $220,893. In 2022, it was $318,297. With this amount of wealth and only 3 percent of the land in Teton County held in private hands, housing prices have skyrocketed.

“The pace of Jackson Hole’s growth and change is accelerating faster than our ability—as businesses, nonprofits, or government—to understand what’s going on, much less effectively address and direct it,” argued Schecter last fall during the 22 in 21 Conference, an event sponsored by his think-tank organization, the Charture Institute. Teton County’s housing crisis is perhaps the most visible example of this. “We are trying to do things that no community in the world has figured out how to do,” he said.

In Judge-Lennox’s opinion, the major hurdle is getting people to visualize the sheer amount of material going to the trash when a home is demolished. She thinks that the government agencies and the public don’t even realize what’s happening when construction waste, estimated at two-thirds of Teton County’s total garbage, can’t be measured accurately because it’s trucked to unregulated salvage yards in Idaho (because this is cheaper than the Teton County, Wyoming, landfill).

If Judge-Lennox is the brains, Victor, Idaho, native Vern Woolstenhulme is the brawn that makes Shacks on Racks possible. Vern’s roots run deep—his family was one of the first to settle in Teton Valley; in 1888 his grandmother Lizzie was the first white child to be born there. In the 1930s and 40s, Woolstenhulme’s father used a team of horses to move small buildings in the winter when the skids could slide on the snow. Like his father, Woolstenhulme supplements farming hay, wheat, and beef cattle with income from other jobs like excavation and moving structures. As the family business, Teton Transport, amassed equipment and experience over the years (bulldozers, frontloaders, hand jacks, and eventually “railroad jacks”), “People just kept calling us to move stuff,” he says.

Before being involved with Shacks on Racks, Teton Transport moved 10 or so structures a year, some as far away as Rock Springs and Salmon, Idaho. Working with Shacks on Racks, the company now moves up to 20. Because every project is different, it’s like a giant Jenga game figuring out exactly where to dig and how to place steel beams under the floor and lift the home with hydraulic jacks that can handle up to 240 tons, all while making sure the lavender tile in the bathroom doesn’t crack.

Woolstenhulme’s most disappointing moment was when a 5,000-square-foot house near Teton Village built in the 1980s with high-quality materials was demolished because the owner was too impatient to wait for the Teton Transport crew to figure out how to move it. “Growing up here, knowing that my ancestors eked out an existence, to see that kind of waste is, well, just sacrilegious,” Woolstenhulme says.

Although the financial and environmental advantages are enticing, a Shacks on Racks home isn’t for everyone. In addition to access to cash and land, you must have time and energy, be resourceful and gritty, and know people who can help. Everyone interviewed for this story mentioned their good luck in finding the rare, conscientious architect, machine operator, banker, or planning department employee who didn’t shy away because it was too hard or not as lucrative as other projects.

“Shacks on Racks provides a unique community service, transporting perfectly good structures and homes out of an existing location so that a home, studio, or workspace can live another life—all while saving space in our local landfill,” says Anne Cresswell, executive director of the Jackson Hole Community Housing Trust. “We are always excited when we find a project for which Shacks on Racks can be a partner. Not only have they accrued significant expertise moving incredibly large objects around our regional road network, but their service helps give another family a home that otherwise would be demolished. If some of these transplanted homes can go to a local worker and keep them in the valley, then that’s a win.”

Meet a Few Shacks on Racks Homeowners

Trissta and Jesse Morgan

A 1930s log cabin moves from Wilson to East Jackson.

Landscape architect Trissta Morgan says she “has thrift in her bones.” It was a necessity growing up in a very large Mormon family in the remote desert town of Boulder, Utah (population 400). After she married Jackson native Jesse Morgan, she says, “It was so hard for Jesse to watch the small homes of friends he grew up with torn down and turned into mega-mansions, and totally losing a sense of place where people take care of each other.” In October 2021, the couple moved the Meadowbrook cabin, which was originally built around 1930 along Flat Creek at Black’s Log Cabin Camp (near where TJ Maxx is today) and moved to the Huidekoper Ranch near the bottom of Teton Pass in the 1970s. They moved it onto a basement foundation next to the longtime home of Jesse’s grandparents in East Jackson. The cabin and Morgan family home, itself on the historic register, sit in what Trissta calls the “hold-out zone,” an area on Glenwood Street just south of the Center for the Arts. Other old buildings in this area include the iconic Gai Mode Beauty Salon. An addition custom-designed for Jesse’s mother will complete the cabin—which is considered an accessory dwelling unit, or ADU, by the Town of Jackson—and provide a space for her to grow older while helping raise her eventual grandchildren.

Katie and Matt Blakeslee

A home moves from East Jackson to Victor, Idaho.

Due to construction supply chain and contractor workforce issues in the fallout of the pandemic, the price of building the dream home Katie and Matt Blakeslee had designed tripled. By March 2022, this made relocating a two-bedroom, one-bath house with a garage from East Jackson to 20 acres they owned in Victor, Idaho, look like a great idea. What was advertised on the Shacks on Racks website (shacksonracks.com) as a “Quaint Home” was cut into three pieces before being loaded onto a semi that took it through Jackson, down to Hoback Junction, up Swan Valley, and over Pine Creek Pass to Victor. Katie nervously drove the pilot car. This was the easy part.

The Blakeslees had a difficult time finding contractors who had the time or willingness to take on the unique, challenging project of putting the home, which had originally been built around 1977, back together and connecting utilities. Matt had hoped experienced professionals would lead them in putting the house back together because, he says, “It was a huge puzzle with no roadmap.” Despite being a constant rollercoaster, the couple thinks it was worth it. They estimate that repurposing the East Jackson home cost them about one-third as much as building a new home. Whenever Matt gets discouraged, he takes heart in thinking about all the materials they kept out of the landfill.

The Langmans

One garage and one cabin moved to a 50-acre farm in Teton Valley.

Judge-Lennox describes Aska Langman as “a powerhouse of a woman—really alternative, really motivated—who dedicates her life to saving baby animals and is as obsessed as I am with saving houses.” On a 50-acre farm in Teton Valley, Idaho, Langman and her family run Aska’s Animals, a nonprofit that houses deserted pets from pot-bellied pigs to puppies. Langman saw a Shacks on Racks move on social media in the summer of 2020, just as construction costs on a small home her husband, Will, was building on their property were increasing. She decided to give it a try.

With the luxury of plenty of land, less-stringent land-development regulations in Teton County, Idaho, and Will’s experience as a builder, the Langmans were able to commit to being able to “move on a dime” with as little as 24 hours’ notice. In March 2022, they moved the old Coey garage (c.1945) from the Jackson Hole Historical Society headquarters on the corner of Glenwood and Mercill Streets. A year later, they moved a 400-square-foot log cabin built in 1996 from Wilson. The garage cost about $10,000 to move, including the concrete slab it sits on; the 400-foot cabin cost about $15,000 to move. On the Langmans’s property, both buildings are still works in progress. The garage will eventually house Will’s carpentry workshop, and the cabin is being restored as a “dry cabin” (no plumbing) to use in the summer as a guest room. Langman estimates it would have cost them between $400 and $500 a square foot to build new. “Still, if my builder husband was not part of the equation, I could have never done it on my own,” she says.

Mack Mendenhall

A cabin moves from Hoback Junction to South Park Ranches.

After purchasing a home in South Park Ranches, local real estate agent Mack Mendenhall began scouring websites advertising government historic buildings being put up for sale. “I love history, and I wanted to have something significant and special to Jackson to add to our land,” he says. When Teton County opened bids on two historic cabins at the confluence of the Hoback and Snake Rivers, Mendenhall jumped at the opportunity to rescue a landmark he and his wife Katie had passed for years as river guides and on family floats.

Both Mendenhall and Judge-Lennox say the move was a nightmare. Teton County gave them only four weeks to remove all asbestos and secure a building permit (complete with engineers’ drawings). It was moved—after being cut in half—during a lunch break in the summer bridge construction on U.S. Highway 26/89 between Hoback Junction and Jackson. Despite the cabin’s roof surviving more than 80 Jackson Hole winters, according to today’s codes, it was not structurally sound and required a completely re-engineered exostructure. “We’ve been writing checks right and left, but I still believe in the opportunity cost of repurposing and upscaling an old structure on my land,” Mendenhall says. “But really, the only way to describe this is a passion project.” JH

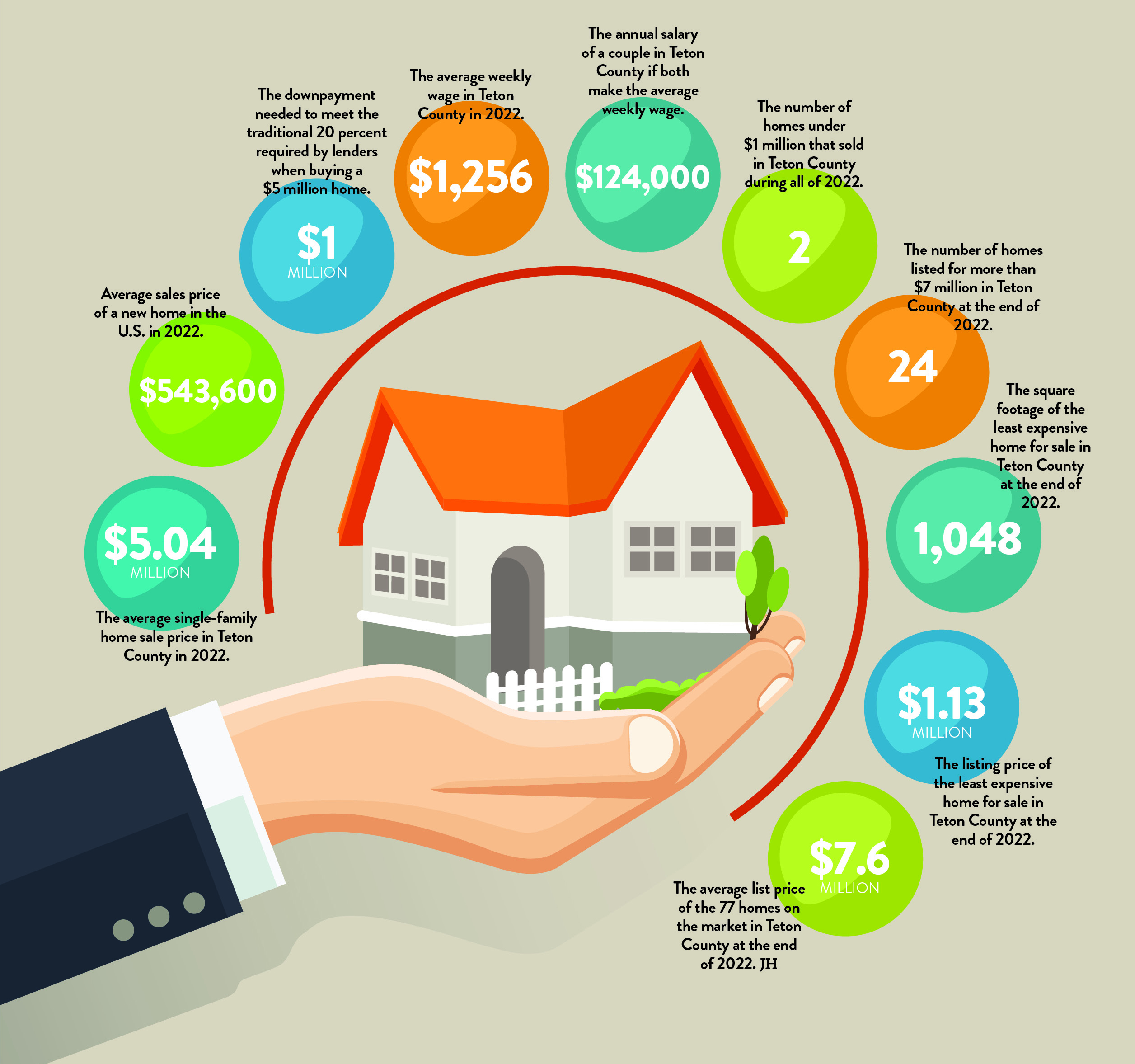

Jackson Hole Real Estate by the Numbers

(All statistics are for Teton County, Wyoming, unless otherwise noted.)