Read The

Current Issue

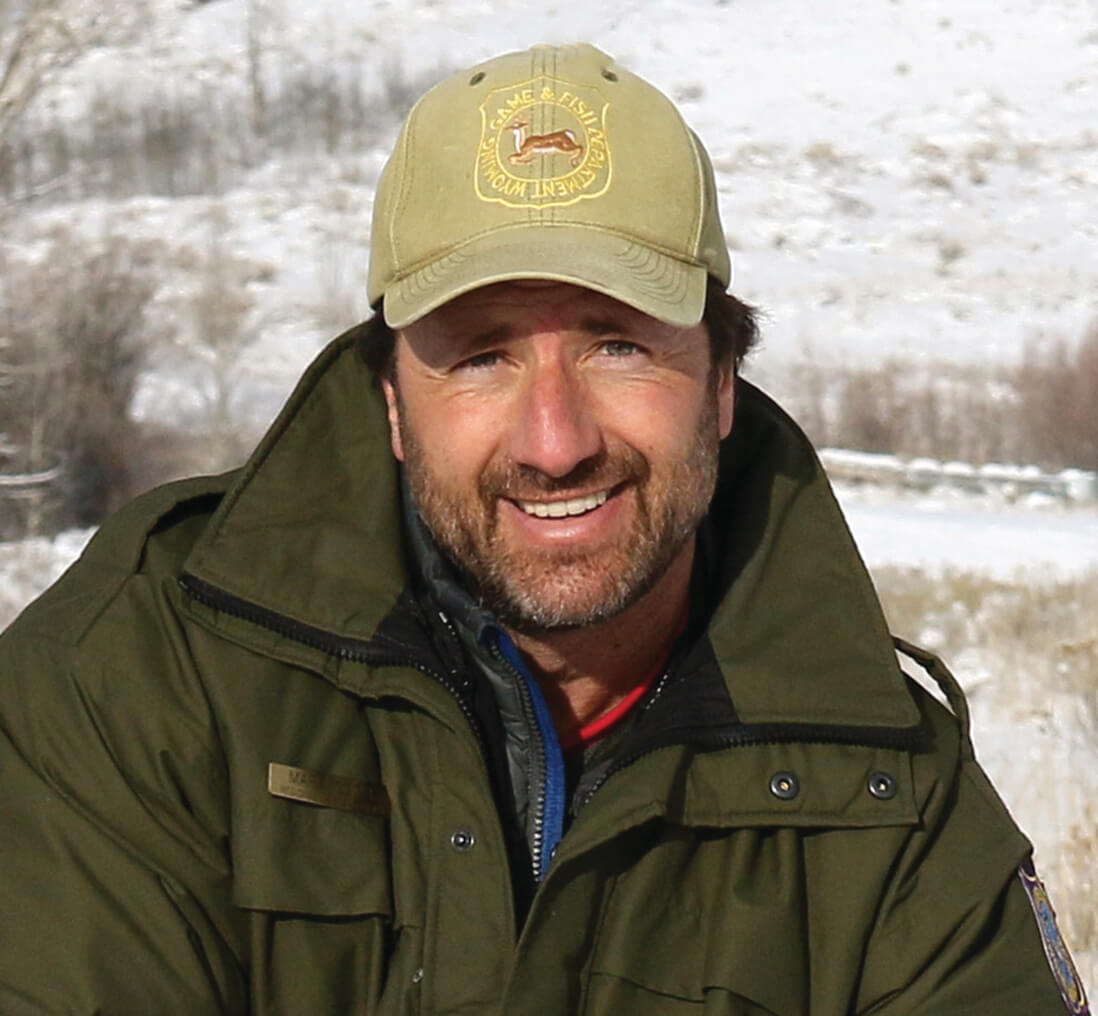

The Wildlife Biologist Behind the Lens

Mark Gocke’s photographs show the hidden—human—side of wildlife management.

// By Billy Arnold

The first time I met Mark Gocke was on a cold December day on the National Elk Refuge. He’d invited me, a fledgling environmental reporter, to cover the Wyoming Game & Fish Department’s annual bighorn sheep capture. As biologists flitted around, retrieving sheep from helicopters so they could poke and prod them for blood samples and fat data that would help determine the health of the herd, the snap of Gocke’s shutter followed them as he took pictures not only of the big-eyed, big-horned animals but also of the wildlife managers studying them.

In a mostly intact ecosystem known for its internationally famous grizzly bears, far-ranging elk and pronghorn, and packs of wolves, Gocke’s most stunning photographs are about the animals and the people working to protect and understand them.

Wildlife biologists are often the face of wildlife management at its most trying moments, like when biologists, hoping to prevent future conflicts, have to kill a grizzly bear that’s repeatedly fed on humans’ trash. “People see that side of it, because it makes news. People care when animals die,” says Gocke, who retired from Wyoming Game & Fish in March 2024. “But that’s why I love these photographs. It’s the positive side of wildlife management, and you wouldn’t find a more dedicated bunch of people.” According to Gocke, people don’t manage wildlife because they love the dirty work. They chase careers with large ungulates and songbirds and fish because they love wildlife, they’re passionate about wild places, and they want to ensure wildlife has a place on this planet.

Gocke first got into photography at his Nebraska high school, when a friend working for the yearbook introduced him to a camera. “That opened up a way for me to be creative,” he says. “I can’t draw, I can’t dance. I can’t, you know, play an instrument. But photography was definitely a way that I could exercise that side of the brain.” At the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Gocke joined the wildlife club, like other kids studying wildlife biology, and won a couple of photography competitions.

But Gocke didn’t set out to be a photographer. He wanted to be a wildlife biologist, and took a job in eastern Wyoming in 1991 conserving habitat on private land. While he loved the job, it wasn’t permanent. So, when a stable opportunity opened to run Wyoming Game & Fish’s Jackson department’s education and outreach efforts, with a side of media relations, Gocke jumped. He moved to Jackson in 1995 and never left. Even though he wasn’t hired as a photographer, he brought his camera into the field, making pictures of bighorn sheep being netted in the Whiskey Basin near Dubois and wolverines poking their heads out of traps. Slowly, he built trust with wildlife biologists who were initially skeptical of his lens.

For 29 years, Gocke served as the photographic eye for wildlife managers in western Wyoming, documenting the human side of wildlife biology and management that most people don’t know about, let alone see. His images of biologists cradling ruby-throated hummingbirds, hand-netting pronghorn, and cramming into bear dens—with sedated bears—capture both the action and the reaction; the light behind wildlife biologists’ eyes as they handle creatures they’ve dedicated their lives to protecting. The hidden, human side of wildlife management.