Read The

Current Issue

Stay Out

Winter wildlife closures protect animals eking out an existence in the cold.

// By Kylie Mohr

Winter is harsh in the Tetons; the temperature can dip to single-digit lows for weeks on end, and the valley annually receives between 6 and 14 feet of snow. Food supplies for animals that don’t hibernate—think moose, bighorn sheep, and elk, among others—are scant, forcing the animals to rely on their body fat for any chance of making it to spring. So, in winter, wildlife are all about energy conservation. Not only are they trying to preserve their stores of fat, which they purposefully built up during the autumn, for as long as possible, but also, when it’s so cold and snowy, moving requires much more energy than in summer.

Humans can pose problems to this, though. Wild animals don’t like being around us (or our dogs) and will flounder through deep snow to flee. Disturbances like these stress the animals and burn serious calories. These encounters not only hurt the animals’ odds of survival and make it harder to fend off disease and predators, but can also impact a mother’s ability to carry viable offspring months later. “When we disturb wildlife in the winter, we force them to expend precious energy, which can lead to poor health and ultimately death, furthering overall population decline,” says Mary Cernicek, a spokesperson for Bridger-Teton National Forest (BTNF).

“Designated winter-closure areas are essential to the survival of wildlife.”

— Mary Cernicek,spokesperson for Bridger-Teton National Forest

Winter wildlife closures of areas to human traffic have existed in Jackson Hole in some form dating back to at least 1983. The goal of these closures is to protect game animals by helping them conserve energy during the most critical time of year. “Designated winter closure areas are essential to the survival of wildlife,” says Cernicek. Today, in the winter in the Jackson and Blackrock Ranger Districts of the BTNF, roughly 120,000 acres are closed to humans. These closures, as well as closed areas on the National Elk Refuge and in Grand Teton National Park (GTNP), are geared toward ungulates, including mule deer, elk, moose, and bighorn sheep.

Important winter habitats targeted by closures include many south-facing slopes in low-elevation areas, which don’t get a lot of snow. This is where animals like deer and elk are likely to congregate. “In areas where the climate is more mild, these types of closures may not be as important,” says Kyle Kissock, communications manager at the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation. “But here, especially where we have deep snow, cold temps, and scarce food, it really makes energy conservation key for the survival of these species.”

Winter wildlife closures are necessary because a large portion of Jackson Hole’s human population likes to play outside. “So many people are drawn to this area for both winter recreation and also wildlife,” says Chelsea Carson, conservation program manager at the Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance. Between 2010 and 2021, Teton County’s population grew by over 11 percent, and recreation trends have followed the population growth. On average, 223 people daily fat bike, cross-country ski, and hike from the Cache Creek trailhead. The popular area’s peak number in winter months is 373 visitors in a day. “We have to learn how to coexist together in that space and be respectful of wintering wildlife because we know it’s a really hard time for them,” Carson says.

BTNF archives have references of closures—primarily focused on small areas like the perimeter surrounding the Alkali Creek and Dog Creek elk feeding grounds as well as places like Leeks and Wilson Canyons—dating back almost 40 years. The closures weren’t prompted by any one incident. “Orders back then didn’t give much information as to the why,” says BTNF spokesperson Evan Guzik.

The original designations didn’t pop up overnight, though. “When they were first decided, this decision was subject to a public review process, as with most federal and state government decisions,” Cernicek says. The same would go for future additions or changes. “For any new revisions to existing closures, there will again be a public review process,” she says. Science guided where winter wildlife closures were originally designated. Biologists and land managers from many agencies, including the BTNF, were involved in the process. The Forest Service manages habitat and not wildlife populations, so state biologists with Wyoming Game and Fish helped determine what animals needed and where.

No new areas have been added in the last 20 years. “They’re those windswept south-facing slopes that are so important,” Cernicek says. “And those don’t change.” But what is changing, she says, is the interface between private land and the public. “We’re having more homeowners and subdivisions and parcels divided and people backing up to the forests,” she says. “And so that educational component—the awareness that you’re in this place and this place is near where these winter ranges are set aside—is important.” Areas where human development interfaces with wild spaces include Nelson Drive and Cache Creek Drive in East Jackson, Game Creek, and clusters of homes near Hoback Junction and down toward Astoria. The BTNF places signs at obvious entrance points to stop visitors before they violate closures as well as relies on public-awareness campaigns.

What started as a promotional campaign 20 years ago is now ubiquitous in the Jackson outdoor community. Heard at annual avalanche-awareness talks and noted at various trailheads around town, the phrase “don’t poach the powder” began as an effort by the Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance and several partner organizations in 2001. A Jackson Hole Guide story from December of that year said that, at the time, the most violations of winter range closures occurred in the Cache Creek area on slopes above the Putt-Putt trail on the north side of the canyon. Local skiers also remembered the community being tempted by Josie’s Ridge and Mt. Hunt, both closed to protect wildlife but with this status less known prior to the campaign.

Years of newspaper advertisements, radio spots, and ranger patrols have gotten the message out. “Now, it’s become a large part of the vernacular in Jackson Hole,” Carson says. Ads in the early 2000s stated that “poaching” wildlife closures with skis, snowboards, or snowmobiles “is as detrimental as poaching with a rifle.” Carson says that while the campaign has evolved over its 20-plus years, largely it’s stayed focused on recreationists who use areas either in or near public lands that are close to sensitive wildlife habitat areas.

The effort is geared toward long-term locals, visitors, and seasonal residents, regardless of how they play in the mountains. “What’s really neat about ‘Don’t Poach the Powder’ is it’s not specific to one type of recreation,” Carson says. “We try to educate all recreationists in the Jackson area and target things folks aren’t thinking about when they go out, such as walking your dog on Cache Creek.” Education includes a Don’t Poach the Powder tab on the Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance website, trailhead signs and maps, and talking about wildlife closures at winter backcountry-travel and avalanche-awareness events.

Winter wildlife closures aren’t unique to Jackson Hole. Seasonal closures of areas important to wildlife in winter exist across the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and region; Wyoming Game and Fish alone closes 165,000 acres of wildlife-habitat-management areas annually to protect wintering big game, including many winter ranges on public lands near Lander, Dubois, and Rawlins that have a variety of restrictions on both human presence and motor vehicles during winter and spring months.

Annually, the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources closes seven wildlife-management areas in northern Utah totaling 45,750 acres of critical winter mule deer habitat. Montana has similar practices. The state’s only wildlife-management unit in the Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest means roads in the Elkhorn Mountains are closed to motorized travel during the winter. A smaller closure in the hills above Missoula, Montana, shields an elk herd that winters on Mount Jumbo from a maze of trails popular with hikers, runners, and bikers. At least seven other Western states, including Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Colorado, have some sort of winter wildlife closures.

Cernicek says that, in general, people tend to follow winter wildlife-closure regulations. “There are reports each year of incursions into closed winter range. But once forest users learn how their actions could potentially affect the wintering wildlife, they often comply,” she says. The incursions are a mix of ignorance and willful disregard; tracks can often be seen from town on Josie’s Ridge, parts of which can be accessed from the lift-accessed summit of Snow King, and Crystal Butte. But the consequences are the same either way, and violating a closure is no joke: it’s a crime that could land you a penalty of up to $5,000 or six months in jail.

“We’ve always had some violations,” Cernicek says. “What seems to be changing is we’re getting more people reporting them. That’s helpful, because we can’t be everywhere all the time and catch everything.” When the BTNF gets a report of poaching, someone is sent out to investigate. If there’s a set of ski tracks that lead to a specific car, great—they’ve got something to go on. But more often than not, all investigators find is the mark of turns or boot prints that are days old and tough to follow. Usually when a report of the first violation in an area comes to the BTNF, staff puts up signage at the entry point to the line. That way, the next person who comes in looking for powder will know more and hopefully turn around. Kissock of the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation says that the vast majority of the public abides by closures. “The challenge for us is getting that last 10 percent,” he says. “We really do hope that locals can be part of setting an example.” JH

scientists have documented that the herd lost up to one-third of its preferred winter habitat because of its desire to avoid backcountry skiers and snowboarders.

A small population of native bighorn sheep lives high in the Tetons, residing above 8,500 feet in elevation on the same windswept ridges that avid backcountry skiers and snowboarders also frequent. Over the last 5 to 10 years, the herd’s size has declined sharply—almost in half, going from 100–125 animals down to between 60 and 80. Experts are worried the herd is in danger of blinking out locally, known as extirpation.

The bighorn sheep don’t like to mix with winter recreationists; scientists have documented that the herd lost up to one-third of its preferred winter habitat because of its desire to avoid backcountry skiers and snowboarders. Two areas within Grand Teton National Park have been closed to humans in the winter for decades specifically to protect these sheep: the summit of Static Peak (since about 1990) and the Mount Hunt/Prospectors Mountain area (since 2001).

But human pressures, as well as competition from other species like mountain goats and also habitat loss, remain a threat to the animals’ survival. The Teton Range Bighorn Sheep Working Group (tetonsheep.org), made up of numerous public and private biologists, has been working since the early 1990s to protect the species. The group has focused on creating awareness about the plight of bighorn sheep and is seeking ideas on how to moderate winter pressure on the herd. A new film, Denizens of the Steep, was released last winter; it explores the impact of backcountry recreation on bighorn sheep through the eyes of professional ski mountaineer and guide Kim Havell (stream the movie on YouTube).

In mid-October, the working group proposed over 20,000 new acres of winter wildlife closures in order to give bighorn sheep more space from backcountry skiers. The recommended closures are in Grand Teton National Park and the Caribou-Targhee and Bridger Teton National Forests. A community collaborative process attempted to gather feedback on where “high-value” ski terrain was, and the proposal would close just 5 percent of that terrain while protecting 50 percent of areas identified as high-quality sheep habitat. But the news was still met with backlash from some prominent mountain guides and pro skiers. The working group also proposed designated routes to travel through otherwise-closed areas as well as increased education and signage. It’s now up to the agencies to decide what, if any, recommendations are implemented.

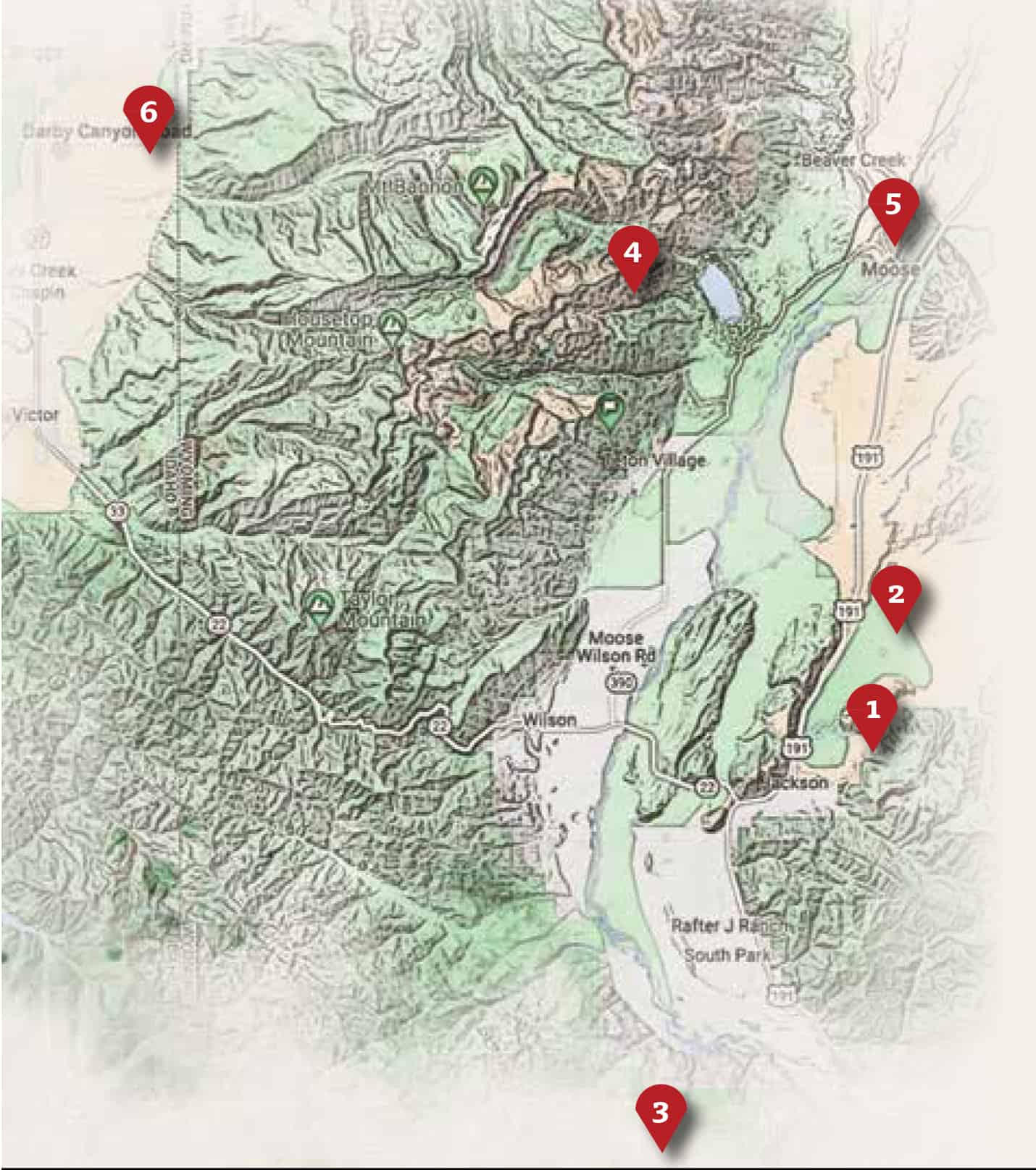

1.Wildlife winter range areas south of Jackson in the BTNF are closed yearly from December 1 to April 30. These include the slopes above Putt-Putt trail in Cache Creek, Josie’s Ridge and KC trails, the slopes north of Game Creek, Porcupine Creek, Horse Creek, Camp Creek, Poison Creek, Dog Creek, and the Fall Creek area near Hoback Junction. While the Putt-Putt and Game Creek trails are not closed, on sections of them, dogs must be on a six-foot leash.

2. To protect elk on their winter range, the Elk Refuge Road closes to all traffic—car, snowmobile, fat bike, pedestrian, skier—about 3.5 miles from its southern end. This means Curtis Canyon and Flat Creek are inaccessible.

3. Munger Mountain and Horse and Camp Creek areas in the forest are closed, as well as a swath of land that stretches between the north side of the Cache Creek drainage to the Gros Ventre River Road (this includes Crystal Butte). You can walk or ride a horse on the Gros Ventre Road and other designated routes, but you cannot leave these roads/routes.

4. Mount Hunt, Prospector’s Mountain, and Static Peak in Grand Teton National Park are closed from December 1 through April 1 for bighorn sheep.

5. Closures along the Snake River floodplain just north of Moose up to the confluence of the Buffalo Fork, the Buffalo Fork River floodplain, and the Kelly Hill area are in effect from December 15 to April 1. These protect moose, elk, bighorn sheep, and waterfowl during critical wintering and nesting periods.

6. From November 27 through April 15, on Caribou-Targhee National Forest land east of Victor and Driggs in Teton Valley, the majority of south-facing slopes in the Tetons are restricted. This includes the areas above Darby Canyon.