Read The

Current Issue

To the Rescue

Teton County Search & Rescue

// By Helen Olsson

Prior to 1993, the year Teton County Search and Rescue was founded, distress calls would come into the sheriff’s office, which would dispatch deputies to respond. Maybe they’d rally a few locals with specific skills or gear to help. “They’d muscle out these rescues the best they could with no training and no equipment,“ says Tim Ciocarlan, one of three volunteers from the original TCSAR class (along with Mike Moyer and Mike Estes) who continue to serve.

The year 2023 marked TCSAR’s 30th anniversary, and there’s a lot to celebrate, starting with a dedicated year-round rescue helicopter, made possible by the Mission Critical campaign, which raised $7.25 million. A rescue ship can mitigate a 20-mile search on foot and, short-haul rescues—where a SAR member dangling from a rope beneath the helicopter can retrieve a patient quickly—are often livesavers.

Since TCSAR’s inception, the rescue profile has evolved. In the early days, the emphasis was on the “search” in search and rescue. Hikers would go missing. Backcountry skiers wouldn’t show for dinner. Cell phones were rare, so rescuers spent hours searching the wilderness with few clues.

Thanks in part to updated rescue technologies like satellite phones and SPOT and Garmin In-Reach SOS activations, today’s TCSAR can pinpoint patients quickly. Rescuers use a Recco SAR detector that hangs from the helicopter to detect Recco reflectors below. The helicopter is equipped with an aerial cellular transmitter called Lifeseeker. “It’s like a magic box that allows us to send a patient a text and triangulate their location, even in areas with no service,” Ciocarlan says. Additionally, TCSAR volunteers now log countless hours of rigorous training, from swift-water rescue to predator attack response.

High-tech outdoor gear and technology have also allowed outdoor recreationists to travel deeper into the wilderness. As athletes push the boundaries, rescue volunteers often need to travel farther—and into more difficult terrain—to reach patients. The good news: public education efforts like TCSAR Foundation’s Backcountry Zero program as well as avalanche-awareness classes are helping to reduce the number of incidents. Ciocarlan says that, historically, most avalanche burial calls ended up being retrieval missions, not rescues. Today, they’re seeing more parties able to perform self-rescues. Backcountry users are getting smarter.

Will Smith

Dr. Will Smith grew up helping his dad run a 22,000-acre cattle ranch in southeast Wyoming, honing his outdoor skills at a young age. During high school, he took an EMT class and started caring for patients in the back of the ambulance—because he was too young to drive. While pursuing pre-med at the University of Wyoming, he moonlighted as a ski patroller at Snowy Range outside Laramie and went on to become a paramedic.

As part of his med school and residency, he spent time doing rotations in Jackson. “I fell in love with the area,” says Smith, who returned to Jackson in 2004 to work as a full-time emergency department physician at St. John’s Health. He joined TCSAR that same year.

“SAR has been the perfect opportunity to blend medicine, EMS, ambulance, and my outdoor passions,” he says. Smith serves not only as co-medical director with Dr. AJ Wheeler for TCSAR, but also for Grand Teton National Park, Bridger-Teton National Forest, and Jackson Hole Fire/EMS.

But there’s more. As a colonel in the U.S. Army Reserves, Smith has had three combat deployments in Iraq, as well as other military medical missions in Croatia, Panama, Egypt, and El Salvador. He spends time in places like Washington, D.C., doing contract work with the Department of State and Homeland Security, consulting on things like tactical EMS for presidential inaugurations.

Smith sees parallels between military and wilderness medicine. “While there are different threats and risks—whether you’re being shot at by bullets or caught in an avalanche—the treatment pathways and paradigms are similar,” he says. Smith also runs TCSAR’s drone program. “A lot of my military experience and the decision-making in critical situations really carries over,” he says.

Ask Smith about memorable rescues, and he’s got a long list: There were the five days of heli-assisted hiking in the Wind Rivers searching for a lost hiker and a 2010 lightning strike on the Grand Teton when 17 climbers were injured at 13,000 feet. And there was the 61-year-old skier who went into cardiac arrest on Maverick Peak in Grand Teton National Park. “We short-hauled in, used the AED, and started CPR,” he says. “Within 10 minutes, he was alert and awake.”

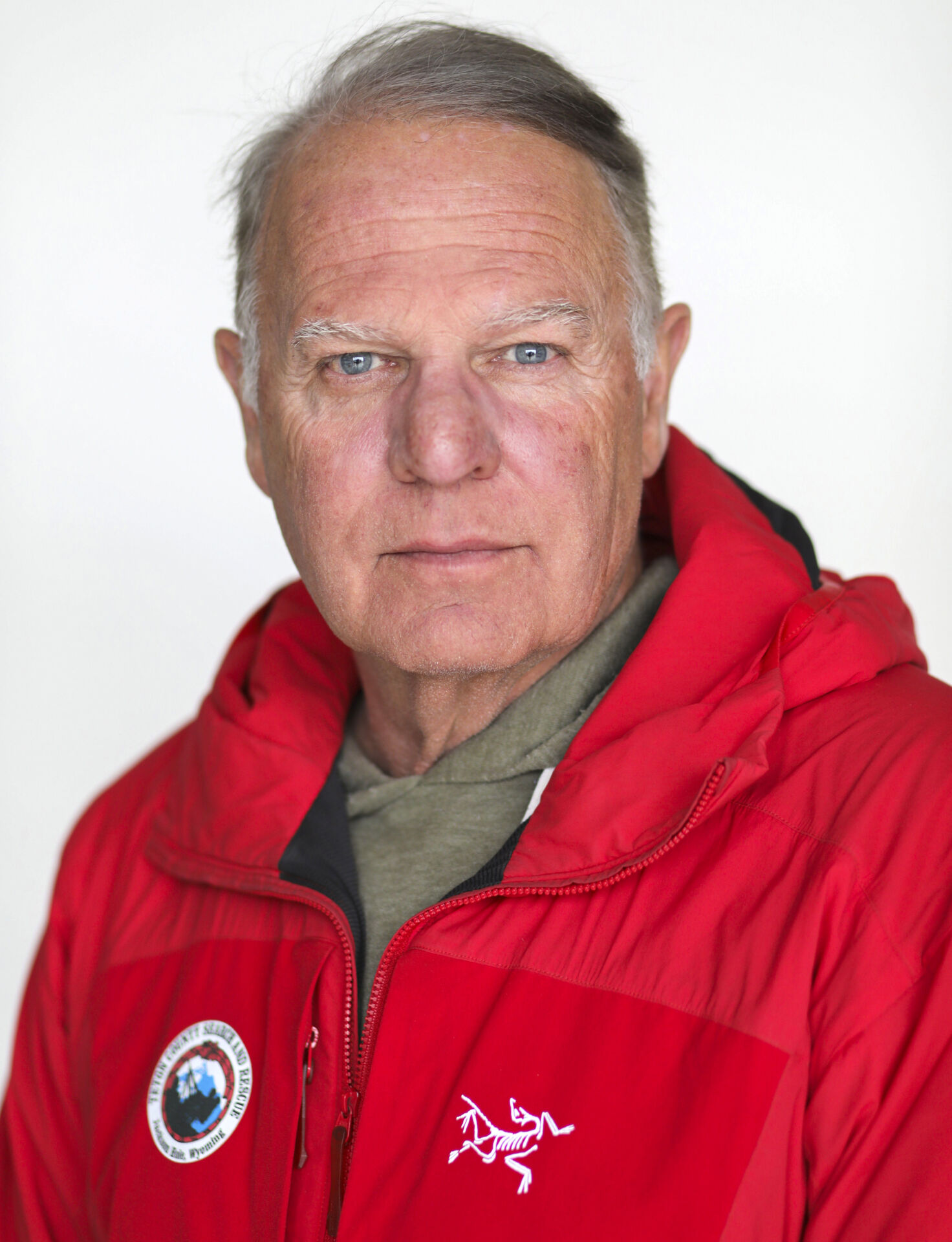

Tim Ciocarlan

As a teenager in the 1970s, Tim Ciocarlan took a ski trip with friends to Jackson and was instantly smitten with the place. Despite being a novice, he rode the chairlift to the top of Targhee on a four-foot powder day. “I fell off at the top, but I made it down. That was the beginning,” he says. To pay the bills, Ciocarlan worked in construction, eventually founding his own construction management company. In the fall of 1992, he saw an ad in the paper that caught his eye. The sheriff’s department was starting the county’s first-ever official search-and-rescue team. “It was a point in my life that I needed diversion. So I applied,” Ciocarlan says.

TCSAR has come a long way in the last three decades. “Back then, people didn’t have personal locator beacons, GPS devices, or cell phones,” he says. Calls for help often came in when a partner hiked miles out of the backcountry to find a pay phone. “Almost every rescue, we’d spend hours searching on foot,” he says. Missions sometimes stretched to 17 hours or more. When TCSAR gets a call today, incident command usually has the coordinates of the patient locked in at the get-go.

Of the myriad rescues that Ciocarlan has been a part of, one that stands out is the 2022 search for Gabby Petito, who was killed by her fiancé in Wyoming’s backcountry. “I treat rescues more or less like business, but, frankly, that one made me cry,” he says.

Will Ciocarlan ever retire? He dodges that question. “When you join up, it’s this amazing group of friends. I don’t think we’re superheroes,” he says. “We’re just ordinary people doing an extraordinary job. And when we get to save the life of somebody’s loved one, that’s pretty special.”

Carol Viau

Carol Viau’s resume is hardcore: Heli-ski guide inValdez, Alaska; commercial fisher in southeast Alaska; Jackson Hole ski instructor and patroller. Today, her paying gigs include guiding in Jackson Hole’s backcountry in winter and on the resort’s via ferrata in summer. One summer on the water in Alaska, she found herself coming to the aid of a man with severe lacerations. She sewed up his arm using a simple needle and thread sewing kit—the kind for sewing buttons onto shirts. “I’d taken advanced first aid in college, so I wasn’t totally clueless, but I didn’t think I should be sewing anybody up,” she says. As a heli-ski guide, she’d had to rescue a client who was swept into a bergschrund by an avalanche. “I’d been seeing a lot of accidents, and I wanted to be more prepared. I wanted to up my personal game.”

In Jackson, Viau got certified as an EMT, taking an intensive month-long course through the Wilderness Medicine Institute. After volunteering with what was then called Jackson Hole EMS (it’s now Jackson Hole Fire/EMS) for a year, she saw an ad for TCSAR in the paper and decided to apply. She joined the team in 2000 and has been volunteering ever since.

Viau is on TCSAR’s short-haul team. Flying through the air in winter, often a thousand feet above the ground, can be a cold, windy trip. But the most dramatic moment is takeoff. “The rotors are spinning. It’s noisy. The snow’s flying. That’s when the adrenaline gets pumping,” she says. “Once you’re in the air, it’s all on the pilot. You reach a point where flying underneath a helicopter is like getting into a car. You’re just used to it,” she says. “The trick is not to get complacent.”

Phillip Fox

It seems fitting that a Boy Scout would end up on a SAR squad. Phillip Fox grew up climbing, mountain biking, and white-water rafting in Tennessee. In college, he worked as a white-water guide for Nantahala Outdoor Center. An opportunity to work at the 2002 Olympics in Park City, Utah, sent him westward, and he eventually moved to Jackson to guide white-water trips in summer and to work in food and beverage at Jackson Hole Mountain Resort in winter. “Like many people, I was planning on spending a year in Jackson,” Fox says. “Twenty-two years later, I’m still here.” Fox’s day job now is director of supply chain at St. John’s Health.

He put down stakes in Teton Valley, Idaho, and signed on with Teton County, Idaho, SAR in 2005. He worked for TCISAR for a decade, during which time he often collaborated on rescues with the TCSAR folks. In 2015, Fox joined TCSAR, and from his Idaho home base—where he lives with his wife, Kristen, and his golden retriever, Dixie—he’s able to respond quickly to rescue calls in Darby Canyon, which is in Teton County, Wyoming, but only accessible with vehicles via Teton County, Idaho. A member of the short-haul team, he was recently certified as a spotter (the brave soul who leans precariously out the open door of the helicopter).

On Fox’s first short-haul rescue, he was tapped to transport an IFMGA-certified mountain guide who’d fallen 100 feet while trying a new winter climbing route on a sharp crag off Teton Pass called The Reef. Fortunately, a couple of snowmobilers happened by. However, by the time TCSAR got the call, it was getting late, and the helicopter wasn’t certified to fly at night. “We didn’t have much time, so I had to quickly package the patient into a Bauman Bag, which is like a vacuum splint with a giant harness system,” he says. With the heli hovering above, Fox and the patient unclipped on Highway 22, which had been shut down to traffic. “We were able to meet the ambulance right there,” says Fox. It made for a Hollywood ending.

Ashley Didion

When Ashley Didion was six, she made a pronouncement: She would be a doctor, marry a vet, have six kids, and live in Jackson Hole. “One of those things came true,” Didion says. In 2016, she moved to Jackson with her husband, Drew, to work as a labor and delivery nurse at St. John’s Hospital.

Didion was on a pre-med track at Mount Holyoke College, where she worked as an on-campus EMT to test the waters of medicine. “It was mostly intoxication—people in high heels falling down at dances,” she says. Through the experience, she discovered the people who were really engaging hands-on with patients were the nurses.

“When I moved here, I was looking for a volunteer service to be more of a part of the community,” she says. She joined TCSAR in 2021 and recently joined the short-haul team. Given the amount of pain Didion sees in the labor and delivery room, she’s particularly able to cope with trauma in the backcountry. “I’m used to people expressing a lot of pain,” she says. “I’m very comfortable with other people being uncomfortable.” The difference is that the pain of childbirth has a purpose. “It’s achieving something. In the wilderness, the pain is telling me something’s wrong.”

For Didion, one of the most surprising facets of a rescue is the parties in peril. “When we show up, the kindness and generosity people feel is remarkable,” she says. And while both patients and rescuers are going through a trauma, Didion points to the TCSAR’s positive and open culture. “It’s a really safe environment for psychological processing. We call it ‘psychological first aid.’”

Rob Sgroi

In a classic moment of irony, Robb Sgroi found himself in need of rescue in the midst of a winter SAR training in 2020. The team was skinning up Snow King resort to build snow caves when he started feeling shortness of breath, GI upset, tunnel vision, and urticaria (hives). He was, in fact, suffering from a condition called exercised-induced anaphylaxis. “My teammates recognized my symptoms and gave me epinephrine. They literally saved my life,” he says. “I can empathize with our patients more strongly now, having been in their shoes.”

Sgroi is a self-professed “native of Massachusetts suburbia” who grew up hiking, backpacking, and skiing in the Northeast. “I feel like I connect with people more strongly in an outdoor setting,” he says. Sgroi took an EMT class in college and, migrating westward, briefly worked as an X-ray tech assistant at Colorado’s Keystone Resort. He went on to pursue a career in natural resource management, moving to Jackson to work for Bridger-Teton National Forest and then the Teton Conservation District. He joined TCSAR in 2004. Sgroi says his wife, Krista, who is a nurse practitioner in orthopedics, is incredibly supportive. “The contributions and sacrifices of the family members of SAR members, I think, are equal to those of the actual team members. SAR work is just so unpredictable,” he says.

For Sgroi, who’s also on TCSAR’s short-haul team, the most memorable rescues involve caves. “I remember getting called to a cave rescue when my wife and I were hosting our engagement party,” he says. “She said, ‘Just go.’” In Darby Canyon, there’s a cave system with waist-high water, ice chambers, and an aptly named labyrinth called The Maze. With limited communication underground, the team often goes in not knowing what they might encounter. “Caves are a setting where SAR needs to employ problem-solving. Maybe it’s building anchors to lower a patient down,” Sgroi says. “We’ve had people spending 30-plus hours in there.” When the team emerges back into the sunshine after a rescue? “That’s a welcome thing.” JH

TCSAR by the numbers

1993

Year TCSAR was founded

10,000

Average total hours TCSAR volunteers contribute in a year

39

Volunteers on the TCSAR team

2

Full-time salaried TCSAR employees

136

Calls TCSAR responded to in 2022

1,200+

People who donated to the Mission Critical campaign to purchase a year-round, rescue helicopter for Teton County

70

Percentage of winter incidents that involve male patients (10-year average)