Read The

Current Issue

Wild, Deadly, and Best Viewed from a Distance

Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks’ views are striking, but it’s often the wildlife that steals the show for the four million-plus visitors who flock to the region annually. Here’s what you need to know to stay safe in their midst—and avoid inadvertently harming wildlife yourself.

//By Mike Koshmrl

The 43-year-old Mississippi woman told National Park Service officials that she had just wanted a photo of herself with a bison in frame.

Standing alongside her daughter near the Fairy Falls trailhead in Yellowstone National Park, the visitor put her back to the shaggy brown animal so large and powerful that wolf packs and grizzly bears choose their battles wisely before engaging. Park officials later ascertained the hulking bison was just six yards away from the Mississipians—about the span of a decently sized kitchen.

Before the photo was snapped, a passerby imparted a warning: Too close. The woman knew it.

“She actually admitted to having read the literature and read the signs, but she saw people too close to the bison so she figured it would be OK,” the late Yellowstone Park spokeswoman Amy Bartlett told

the Jackson Hole Daily at the time.

According to the account detailed in the newspaper, the woman and her daughter heard bison footsteps approaching from behind.

They began to run.

Too late.

“The bison caught the mother on the right side, lifted her up and tossed her with its head,” park officials reported at the time.

The middle-aged Mississippian’s father acted instinctively, just like the bison. He dove on top of his daughter and “covered her with his body to protect her.” That’s not recommended. The irritated bison could have easily gored him, too. But fortunately, it worked. The bison moved off about three yards, the tourists scrambled for safety, then headed for the Old Faithful Clinic to get their non-life-threatening injuries checked out.

The woman could have had it much worse. She was charged and tossed on a Tuesday in late July of 2015, a summer when five Yellowstone tourists were injured by bison. Of the five (three U.S. residents and two visitors from abroad), four were gored—opened up—by bison horns. “The other four injured were all life-flighted because of puncture wounds, and she was not, so she was extremely lucky,” Bartlett said at the time.

Five in a single season is unusual. But the reality is that a bison goring or two is unfortunately an expected part of a Yellowstone National Park summer. Historically, conflict has been inevitable when you add four to five million tourists to a landscape that’s home to healthy populations of toothy, large, and/or antlered megafauna. Yellowstone and its neighboring Grand Teton National Park have very clear instructions plastered on signs, websites, and in pamphlets distributed at entrance gates: always stay at least 100 yards from bears and wolves and 25 yards away from all other animals. Nevertheless, the messaging oftentimes is ignored, missed, or gets metaphorically lost in the crowd by people who, in many cases, are in awe of wildlife they’re seeing for the first time in their lives—like bison, a species that was nearly wiped off the planet a century and a half ago.

The National Park Service does what it can to avert bad outcomes. Besides rangers and signage, there are volunteer-based units like Grand Teton National Park’s wildlife brigade whose sole purpose is to keep people and fauna safe when they mix at places like roads. And on top of that, there are people like Jackson Hole resident Jesse O’Connor, a professional tour guide who carries a whistle on his belt and who considers it his duty to help educate park visitors—and intervene when they’re making poor choices. “I will let them know; I will say, ‘Too close! 100 yards away!,’” he says.

Making poor decisions

O’Connor, who spends an average of 60 days guiding in the parks annually, perceives a mixed bag of human behavior leading to wildlife interactions going sideways. Some tourists really do miss the warnings, come from large metropolitan areas lacking wildlife, and are naive about the danger. But a significant percentage of people are willfully dismissive of the rules. “There are a lot of people who say, ‘That isn’t going to happen to me, the rules don’t apply to me,’” he says. “People make dangerous assumptions because they think they know better, and that’s getting worse and worse. Rejection of authority.”

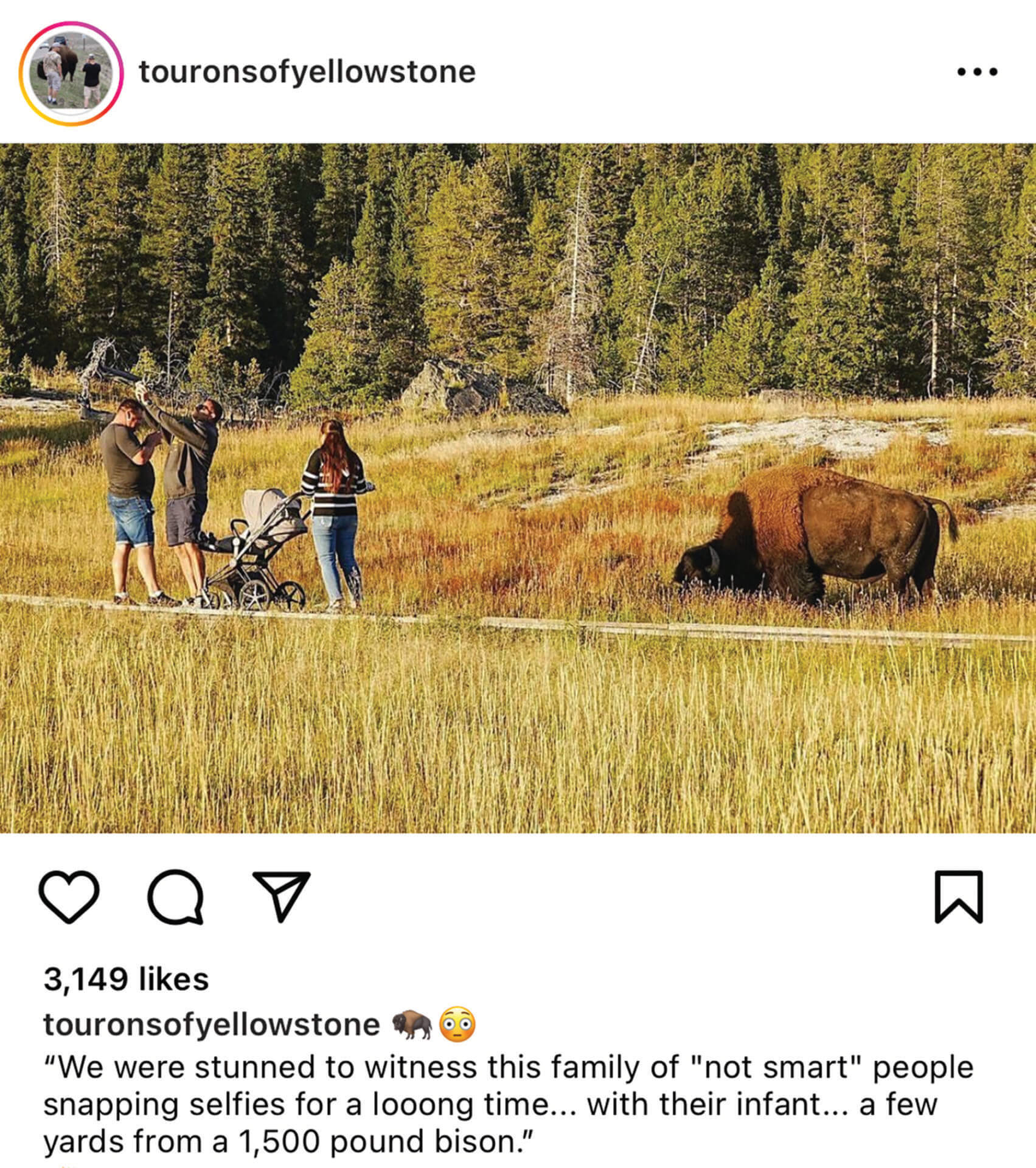

Often, it’s the most flagrant disregard for the rules that earns the most attention. There’s an Instagram account devoted to documenting the behavior—@touronsofyellowstone, with a half-million followers—and there’s a good chance you’ve seen footage and online outrage stemming from these incidents, which often go viral. There was the drunk guy in 2018, Raymond Reinke, taunting a bison in the middle of a road during a bison jam. Or the clip from August 2023, when a group of Yellowstone tourists sprinted down the road to get a closer look at a roadside black bear sow with two cubs—a potentially perilous decision. Or the viral story from 2016, when a Canadian visitor “saved” a bison calf from the cold by putting the young animal in his trunk, leading to the calf’s death (separate a calf from its herd and mother, and that can be the outcome: a mercy killing of a young defenseless animal that’s going to suffer if left on its own).

That list could keep going and going.

There’s also an inverse to the most headline-worthy, shockingly ignorant, disrespectful human behavior. Yellowstone’s Mary Wilson, a ranger based at park headquarters in Mammoth Hot Springs, has seen situations time and again where tourists put themselves in harm’s way without even realizing it. Oftentimes, what happens in Mammoth looks like this: A cow elk is grazing or bedded in the developed area, and its newborn calf is tucked out of sight nearby. The visitor might not even be interested in the elk but wants to get to the picnic tables, bathrooms, Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel, or another destination. Mama elk’s protective instincts kick in, and just like that an unknowing visitor has been rammed to the ground and is being pummeled by elk hooves. This exact scenario unfolded twice in three days in early June of 2018—and one of the recipients was a seasonal Yellowstone concession employee. “Most of the time, they don’t know,” says Wilson, a Yellowstone North District ranger in the Resource, Education, and Youth Programs division. “They don’t know there’s a risk because they’re so excited to see an animal.”

Yellowstone officials do what they can to prevent these types of accidents from occurring. During the elk rut in Mammoth—a time of year when it’s the bulls that get irascible—they erect prominent signs warning tourists. “We have a lot of temporary signs that we’ll put in the ground for maybe just 20 minutes,” Wilson says. “My staff, they do a lot of sign-moving and barricading and coding. We really actively manage that.” And Yellowstone’s preventative work goes beyond signage. From September into November, they actually remove the picnic tables from the front of the Albright Visitor Center—an area where rutting bull elk like to congregate. At night they even close off the parking lot nearest the visitor center. “We get everybody out by five o’clock, so people can’t park in there and be right on top of all the animals,” Wilson says. “But they can still enjoy them, just from a distance.”

Success stories

Yellowstone has had success in turning the corner on chronic conflict between tourists and wildlife, most notably with grizzly bears. In the 1970s, park officials closed off garbage dumps that dozens of grizzlies had depended on for their main source of calories. Simultaneously, they installed bearproof infrastructure throughout the park: bearproof garbage cans and dumpsters, and poles in the backcountry for hanging food bags. And, at the same time, rangers stepped-up education efforts, slowly starting to enforce food-storage regulations.

Prior to all these changes, grizzly bears and humans were in a constant state of friction. Kerry Gunther, Yellowstone’s lead bear biologist, runs through the numbers. “We used to average about 138 bear-caused property-damage incidents per year, and 48 human injuries per year,” he says. “Now, we’re down to less than a dozen [overall conflicts]. And visitation has gone way up.” Bear-caused human injuries have declined by a remarkable 98 percent. Now, Yellowstone averages a single mauling a year. “And those are almost always surprise encounters in the backcountry, primarily with females with cubs,” Gunther says.

Gunther credits the extraordinary downturn in conflict to Yellowstone’s education campaign—and to tourists listening and changing their behavior. “We’ve hammered the message since 1970 not to feed the bears,” he says. “It’s actually more common for somebody to try to feed a coyote or an elk than a bear.” Nowadays, most of Yellowstone’s bear-caused human injuries are not from people making stupid decisions, but rather are just from bad luck and bad timing. There’s likely an element of inevitability explaining the remaining conflict. Mix millions of tourists—many urban folks ignorant of wildlife’s true danger—with a healthy population of grizzly and black bears, and something is bound to happen, regardless of whether there’s signage, attentive ranger corps, and other visitors around to help police each other. “The holy grail for me would be to have a year with no conflicts,” Gunther says. “I just don’t think we can ever get there with over four million visitors. People make mistakes. They’re on vacation and thinking about other things, and we’re pretty happy with how low we have conflicts.”

In the Tetons, the wildlife is at your mercy

Grand Teton National Park hosts a similar number of annual visitors as Yellowstone. But perhaps because of geography and where wildlife congregates, in the Tetons, there are far fewer bison gorings, elk tramplings, and other wildlife run-ins that tend to cause human injuries. That’s not to say the more southerly, smaller park is immune to human-wildlife conflict.

In the heavily trafficked Jenny and String Lake areas, there are years where there are chronic issues with habituated, food-conditioned black bears targeting picnicking visitors. Oftentimes, it’s not the result of deliberate wildlife feeding. Rather, a guest leaves a backpack unattended while going for a dip in the lake, and a savvy bruin takes advantage. Unfortunately, the behavior often doesn’t pan out for the bears. Although park rangers attempt hazing animals, there’s a point where the intelligent ursines become too hooked on human-associated foods. Almost inevitably, those animals are considered unsafe and end up dead—put down by rangers.

And it’s not just black bears. Sporadically, there have been issues with foxes and coyotes boldly approaching Teton Park visitors looking for handouts. On a couple of occasions, those foxes have stopped responding to hazing operations. “That could be enough to euthanize an individual,” Grand Teton Park biologist John Stephenson says. Moral of the story: Don’t feed the foxes. Or any other wild animal.

Your wildlife safety guide

Both Yellowstone National Park (nps.gov/yell) and Grand Teton National Park (nps.gov/grte) have an abundance of wildlife-viewing information posted on their websites—and in many other places. “We have a lot of avenues,” said Teton Park spokesman C.J. Adams (who has since switched jobs to work for the Bridger-Teton National Forest). “We have the Wildlife Brigade to interface with people directly. Beyond that, we do a lot of social media posts. There’s messaging in our park newspaper that’s handed out at the gates and visitor centers. And we work with the Grand Teton National Park Foundation and Bear Wise Jackson Hole to get those messages out to the public.”

The messaging will tell you where to go. In Grand Teton, for example, head to Mormon Row in spring, summer, and fall for a shot at viewing the park’s migratory pronghorn. But there’s also guidance on how to stay safe. The short of it: keep a reasonable distance. Those distances differ depending on the species, and they’re regulated and aligned in the two national parks.

“Whether you are in your vehicle or on foot, you must maintain a distance of at least 100 yards from bears and wolves, and 25 yards from all other wildlife,” Teton Park rangers warn online. “Animals in the park are wild and may act aggressively if approached.” These distances are a minimum though; if an animal is reacting to your presence, you’re too close.

There are also more-elaborate third-party guides that are tailored to wildlife safety in the region. One of those, available for free online (grizzly399.org/dl_guide.php) was funded and compiled by the Deidre Bainbridge Wildlife Fund, named after the late environmental advocate and Jackson Hole resident. The guide has general biological information and tips for wildlife viewing, and also specialized information about how to do so safely. It’ll tell you, for example, how to recreate safely with a dog in a wildlife-rich environment like the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. A couple of pointers: It’s illegal to take your pooch into the backcountry or on frontcountry trails in Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks. On the national forests adjacent to the national parks, dogs are allowed, but never let yours chase wildlife. It could earn you a fine, or worse. JH