Read The

Current Issue

Yellowstone at 150: A Time for Celebration & Reflection

Yellowstone’s resources are as healthy now as they’ve been since the park was founded, but that wasn’t always the case, and we have work to do to ensure they stay that way for future generations.

// By Mike Koshmrl

It is part of Cam Sholly’s weekly routine to confront concerning headlines: park wolves getting shot when they wander outside the park, grizzly bear conflicts, bison gorings, derelict infrastructure, yet another record visitation year, yet another tourist making a bad decision by a hot spring. The list goes on.

Amid that noise, Sholly, the superintendent of Yellowstone National Park, is fond of taking a step back and reminding people just how far their park has come. “The health of the ecosystem is better than it has been since before Yellowstone became a park,” he says. “Remember, we’ve only really put the pieces back together over the last 50 years.” The assemblage of those pieces starts with the restoration of the big, toothy mammals on which Yellowstone today hangs its reputation. Functional populations of wolves were wiped out of Yellowstone by market-driven bounty hunters’ poisons and bullets by the 1920s, then were successfully reintroduced in 1995 and 1996. Some 31 wolves taken from western Canada (joined by 35 more released in central Idaho’s wilderness complex) and released in the park proliferated and have since spread to Oregon, Washington, California, and, most recently, Colorado.

By the time of Yellowstone’s centennial in 1972, its grizzly bears were just getting out of the dumps, literally. Hunted down outside the park and hooked on garbage to the joy of bear-crazed tourists, the region’s grizzly population hit a nadir of 136 animals in 1975. Shortly after, the Endangered Species Act was signed into law, charting a policy path for conservation, and it worked for grizzlies. Today there are 1,000-plus grizzlies dwelling in Yellowstone and well beyond. These are just two of the successes. Bison and bald eagles were also brought back from the brink of extirpation. And Yellowstone has made headway on myriad of other environmental challenges, from protecting its geothermal features from people to waging a battle against nonnative trout.

This complex puzzle is today visited annually by almost 5 million people, and celebrated globally with publicity, including an issue of National Geographic dedicated entirely to the park: the 170-page May 2016 issue included stories on everything from the park’s microbes to the reintroduction of wolves. One hallmark of 2.2-million-acre Yellowstone and its surrounding interconnected mass of federal lands—about 22 million acres collectively known as the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem—is that it still has all the wildlife that inhabited the Yellowstone Plateau prior to the arrival of Anglo-Americans. And it’s not just terrestrials: the region’s native fisheries are also as intact as any in the Lower 48. Look no farther than the headwaters of the Snake and Yellowstone Rivers to find robust populations of cutthroat trout, the native species. The ecosystem overall, like Sholly says, has improved, and the land itself and its wild inhabitants are now less compromised by human activity and extractive industries than they were at Yellowstone’s golden anniversary in 1922 or its centennial.

Yellowstone has made headway on a myriad of environmental challenges, from protecting its geothermal features from people to waging a battle against nonnative trout.

earliest days, has long since been considered folly and phased out. Courtesy Photo

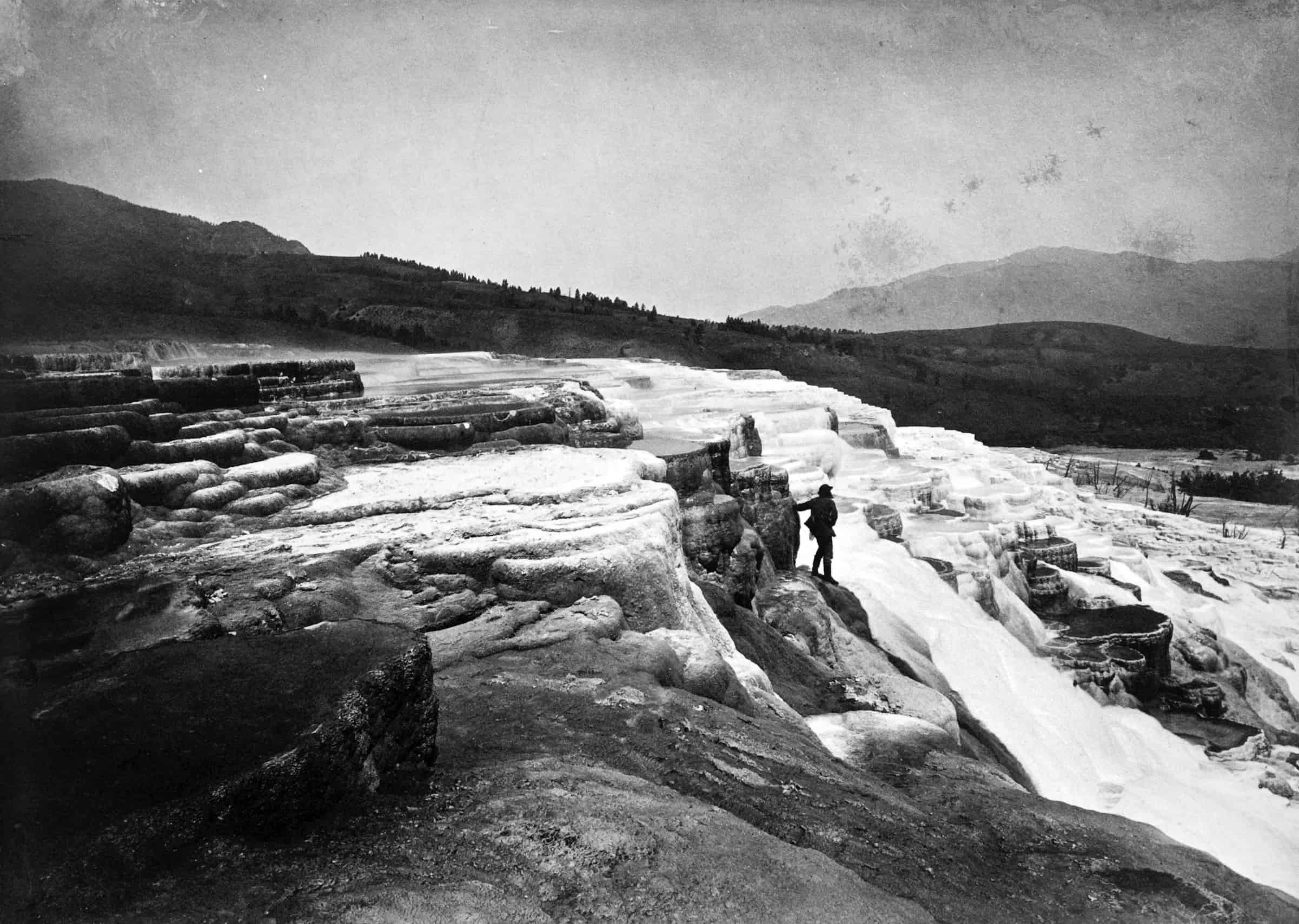

Yellowstone was created on March 1, 1872, when President Ulysses S. Grant signed the Yellowstone Park Protection Act, which stated the government was: “To set apart a certain tract of land lying near the headwaters of the Yellowstone River as a public park.” The boundaries were somewhat arbitrary. Essentially, the government, using findings from Ferdinand Hayden’s 1871 expedition, drew a square on a map that included Yellowstone Lake, the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River, Mammoth Hot Springs, and several geyser basins. Even if the park’s boundaries were rather arbitrary, the action by the U.S. Congress in creating it was historic. Yellowstone was the nation’s first landscape protected for preservation’s sake alone, and its designation begot a new way of thinking about how Western settlers ought to treat the frontier’s expansive open spaces.

The tale of Yellowstone’s history is not all honorable, however. Scott Christensen directs the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, an advocacy group based in Bozeman, Montana, and says it’s certainly worth celebrating Yellowstone’s wins this sesquicentennial year. The park and its partners, he says, put an immense amount of time, energy, passion, and money into restoring wildlife like bison and grizzly bears and wolves, which are now integral to Yellowstone as we know it. “But we also need to recognize that the creation of the park came at the expense of removing the native people,” Christensen says. Today, there are two reservations within the GYE where the tribes have persisted: the 2.2-million-acre Wind River Indian Reservation, home to the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho; and the 520,000-acre Fort Hall Reservation where the Shoshone-Bannock tribe dwells along the region’s southwest flank. Although these are the nearest contemporary Native people, there are 49 tribes still existing today with some kind of ancestral connection to Yellowstone.

Although a traditional bison hunt is permitted in Montana just outside Yellowstone’s northern boundary each winter, the native people’s traditional use of the park itself has been functionally severed since around the time of the park’s creation. “The actual creation of the park isn’t really anything to celebrate for indigenous people, because there’s some dark history there,” says Wes Martel, an Eastern Shoshone tribal member who recently joined the Greater Yellowstone Coalition to lead a new tribal bureau based on the Wind River Indian Reservation. “Over the decades, Congress and the courts have systematically excluded us from having any type of involvement with our aboriginal homelands. When you go back to the treaties and the aftermath, that really shows the deceit and vindictiveness and the evil approach that the colonizers and the Christians had.” What is worth celebrating to Martel are the tribes still around today. Their presence provides him with hope that the first people’s ancestral connection to Yellowstone can be repaired. “We need to reconnect to the park,” Martel says. “When indigenous people want to go out and gather and utilize our traditional homeland in a traditional way, they get fined. What the Park Service defines as a violation, we define as a relationship.” To that end, in early June, tribes are convening on the Wind River Indian Reservation to discuss their roles with the national park going forward.

The National Park Service is also engaging in that dialog. “We’re trying to get it right, too,” Sholly says. “We’re putting a heavy emphasis on the tribes and the tribal presence in this area prior to Yellowstone becoming a park, and we want to make sure we’re doing a better job in the next 150 years.” Like tribal relations, Yellowstone’s land and wildlife management in the late 19th century was also a long way off from the ideals of today. For starters, there was no federal agency nor federal funding to guide the park down the path toward conservation. For Yellowstone’s first 14 years, civilian superintendents were in charge, and they were poorly equipped to dissuade poachers who thinned out ungulate populations, souvenir hunters who pilfered geyser basins, and developers who built commercial camps near hot springs. Finally, in 1886 Congress appropriated resources to help administer the park. That year, the U.S. Army came in to help—specifically, men from Fort Custer under the command of Captain Moses Harris—and the military personnel stuck around for 32 years, until Yellowstone’s jurisdiction shifted to the newly created National Park Service. This new federal agency, a product of the 1916 Organic Act, didn’t have all the answers, either, though. “We failed miserably early on,” Sholly says. “We got it wrong. Look at the extirpation of predators that occurred just 100 years ago. We were feeding bears out of garbage dumps in the ’60s.” (The once-popular practice, which made grizzly viewing easy, was disbanded in 1970, when Yellowstone closed the dumps “cold turkey,” leading to a spike in bear mortality).

“We’ve got to carefully analyze what we did right and what we did wrong in the last 150 years,”

— Cam Sholly, Yellowstone superintendent

It was only once Yellowstone hit the century mark in the 1970s that the National Park Service, and American society more generally, changed course. The catalyst was a suite of a couple dozen laws Congress enacted to protect land, water, and wildlife, says Luther Propst, who founded an environmental think tank, the Sonoran Institute, long before being elected as a Teton County commissioner. Those policies, like the Endangered Species Act and National Environmental Policy Act, were the product of a nationwide environmental awakening that emerged from widespread contamination of the United States’ lands and water. Propst says the policies “worked pretty well” at reigning in the worst effects of industries—like logging and mining—that, at the time, most threatened the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

In modern times, as the traditional extractive industries that once exploited wildlands in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem largely faded into history, the threats have changed. “Now the West has changed dramatically,” says Propst, who has worked in the wildlife and conservation world for 30 years. “New West” threats, he says, have taken their place: wealthy retirees subdividing pastures into lots for second homes, remote workers piling into Western resort communities in the aftermath of the pandemic, tourists showing up in unprecedented numbers, and recreationists who are multiplying and pressing deeper into wild places. “We do not have a framework for dealing with this new generation of threats,” Propst says. “At its core, it’s a lot easier to regulate a discreet industry than it is to regulate us and ourselves.”

as a national park in March 1872. WILLIAM HENRY JACKSON, U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF THE TERRITORIES

Threats people pose to Yellowstone start with our ever-growing headcount. Around the globe and in northwest Wyoming, we’re continually increasing, both in numbers of residents and visitors. Sholly can run the million-visitor increments off the top of his head: 1948 was the first time Yellowstone hit 1 million, in 1965 it drew in 2 million sightseers, and the 3-million threshold was eclipsed in 1992; the 4-million mark was passed in 2015. Technically there were 4.86 million visitors logged in 2021, though park officials caution that the figure was inflated by some lodging-related methodology quirks.

But, by no means is Yellowstone always overrun. Within the park, there is no evidence that visitors are directly causing significant ecological damage at present, Sholly says. The vast majority of visitors don’t travel off boardwalks and the most heavily trodden trails. But infrastructure in parts of the park is increasingly stretched to the max, especially in the peak of summer. “The facilities really haven’t changed substantially since the ’60s, yet the number of visitors has more than doubled in just the last 40 years,” says University of Utah law professor Bob Keiter, who’s published extensive literature about the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. “I remember early on when I was at the University of Wyoming, it was a major news story when Yellowstone surpassed 2 million visitors. Now it’s more than doubled.” Covid-19 seems to have exacerbated past trends. Where the numbers go moving into Yellowstone’s next 150 years is tough to predict, but there are practical limits that will put a stop to the exponential growth. “There’s a point where you cannot allow more people to come in,” Sholly says. “It’s not necessarily because of massive resource damage. It’s because of gridlock.”

Threats to Yellowstone also emanate from outside the park. Recreation is booming—be it backcountry skiing, mountain biking, trail running, or backcountry bowhunting for elk—and the pressures from those pursuits are not insignificant, argues Dennis Glick, who recently retired from the Bozeman-based community-planning nonprofit FutureWest. “I think that the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is as threatened by the development in recreation that’s happening right now as it is threatened by climate change,” Glick says. “That might seem like a radical statement, but I believe it’s absolutely true.” He worries that those who keep an eye over Yellowstone are doing too little too late to address the cumulative impacts of human recreation, which range from backcountry skiers displacing bighorn sheep from their Teton Range winter habitat to trail building throughout the region infringing on elk calving grounds. “The rapid increase in the number of people recreating in our region is definitely a cause for concern,” says the Greater Yellowstone Coalition’s Christensen. “I know what it feels like to pull up to a trailhead with 100 cars at it; I know what it feels like to try to put my raft in the river and be the 20th car in line at the put-in.” He called for a large investment in studying the effects of recreation: “Let’s understand what the real impact is in these hotspots, and let’s address it.”

The idea of managing Yellowstone as a region—and term the “Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem”—was introduced as long ago as the 1960s. The phrase can be traced to John and Frank Craighead, famous grizzly biologist brothers who called Jackson Hole home. “It was used by the Craigheads, in conjunction with their 1960s grizzly bear study,” Keiter says. “Then it was picked up by the conservation groups.” A couple decades later, a federal collaborative known as the Greater Yellowstone Coordinating Committee attempted to strengthen the ecosystem concept and pursued giving it some regulatory teeth. That committee is composed of all the federal land managers in the region plus the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. In the late ’80s, the coordinating committee launched a high-profile “Vision” exercise to establish region-wide management goals and planning protocols. “That scared some people, and the politics were such that during the George H. W. Bush administration, they ended up killing it,” Keiter says. Afterward, the Greater Yellowstone Coordinating Committee developed a reputation as ineffective, with little influence over the ecosystem.

Propst, Glick, Sholly, and Keiter all told Jackson Hole magazine that a key to upholding Yellowstone’s and the GYE’s ecological integrity in the long run will be effectively managing its natural resources and human-related threats across boundaries. Keiter, the law professor, says that today the state and federal agencies are failing to cooperate when it comes to managing Yellowstone’s wildlife, which know no boundaries. “Better collaborative relationships are going to be essential,” he says. During Montana’s 2021–22 wolf-hunting season, for example, at least 25 wolves that dwell primarily in the park, but sometimes wander outside, were killed by state-sanctioned hunters and trappers. That hunter harvest—a record high in the 27 years since wolves were reintroduced—was enabled by the Montana Legislature, which went over wildlife managers’ heads in 2021 and changed the law to prescribe aggressive hunting seasons on Yellowstone’s doorstep. It worked. Yellowstone’s habituated wolves were easy targets. The hunt eliminated a fifth of the park’s approximately 125 wolves, disrupting social dynamics among the wolves that remained. Yellowstone wolf watchers from around the globe were outraged, and so was the Park Service, whose objections fell on deaf ears.

Also looming are private land threats outside of the federal agencies’ authorities. Nearly a third of the ecosystem is privately owned, and the development of that land is intensifying. A 2018 peer-reviewed study in the journal Ecosphere found that the human population doubled and housing density has tripled in the GYE since 1970. Both measures of development are projected to double again by 2050. Policies guiding growth across the ecosystem are a patchwork due to jurisdiction issues: the region spans three states and 25 counties. Foremost, rapid growth along the ecosystem’s fringes threatens ecologically important resources. If growth of fast-growing gateway communities like Bozeman, Montana; Teton Valley, Idaho; and Jackson Hole continues at rapid clips, the worst-case-scenario picture of the Yellowstone region 150 years from now is grim. “We’ll have some islands of wildland and wildlife, but we’ll no longer have a functioning large wildland ecosystem,” Glick says. “And I think that’s what makes Yellowstone so special.” In this hypothetical scenario, he says, tourist satisfaction—which remains high today—will suffer. “For example, driving down the Paradise Valley in Montana [north of the north entrance to Yellowstone at Gardiner, Montana] is jaw-droppingly beautiful,” he says. “But if it becomes strip development and rural residential sprawl, that will diminish the visitor experience.”

In a general sense, Yellowstone’s superintendent wants to see the big sesquicentennial be much more than just a celebration. It’s a good time to reflect on the past, he says, and take everything they’ve learned—including beyond park boundaries—to chart a plan for the next century and a half. “We’ve got to carefully analyze what we did right and what we did wrong in the last 150 years,” Sholly says. If we do that and make hard decisions, Glick is optimistic about Yellowstone’s future. “Every day I am encouraged by the number of people I get to interact with that care deeply about the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem,” he says. “I’m not naive enough to think that we can save it all. But I have hope that we will, as a community, make good decisions on behalf of this place.” JH