Read The

Current Issue

SMITHSONIAN AMERICAN ART MUSEUM

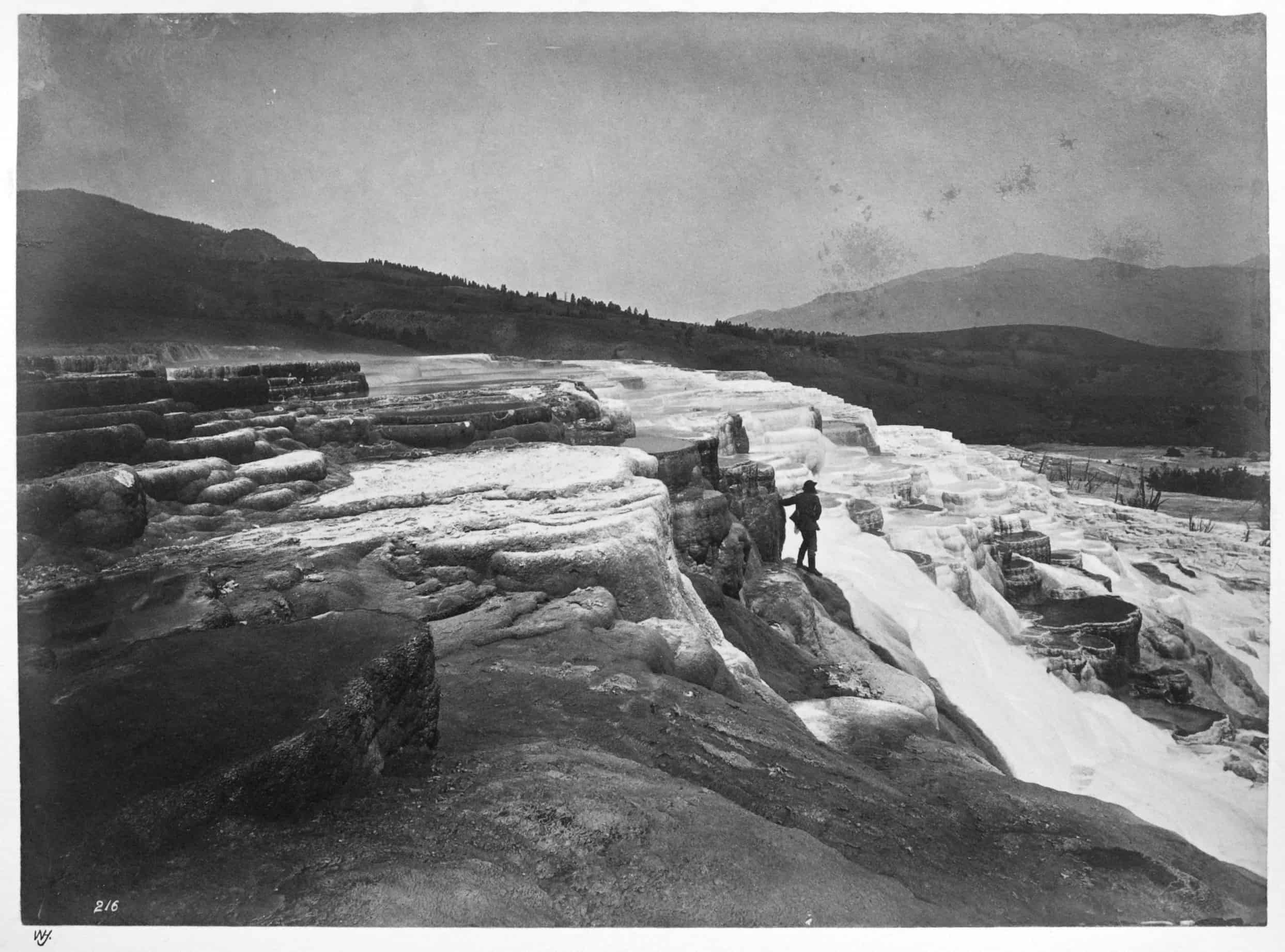

The 1871 Hayden Expedition’s meticulous and vivid documentation inspired awe, convincing Congress to designate the first national park the following year.

// By Mike Koshmrl

Pronghorn, cutthroat trout, and fresh buttermilk fueled Ferdinand Hayden and his fellow expedition members in the days before they set off to map, measure, paint, and photograph what would soon become Yellowstone National Park.

The mosquitoes were bad in mid-July of 1871, and so the large party of young men that accompanied the forty-one-year-old University of Pennsylvania geology professor “smudged” the swarms of insects by burning bison patties that littered the Gallatin River valley, where it was staged at Fort Ellis.

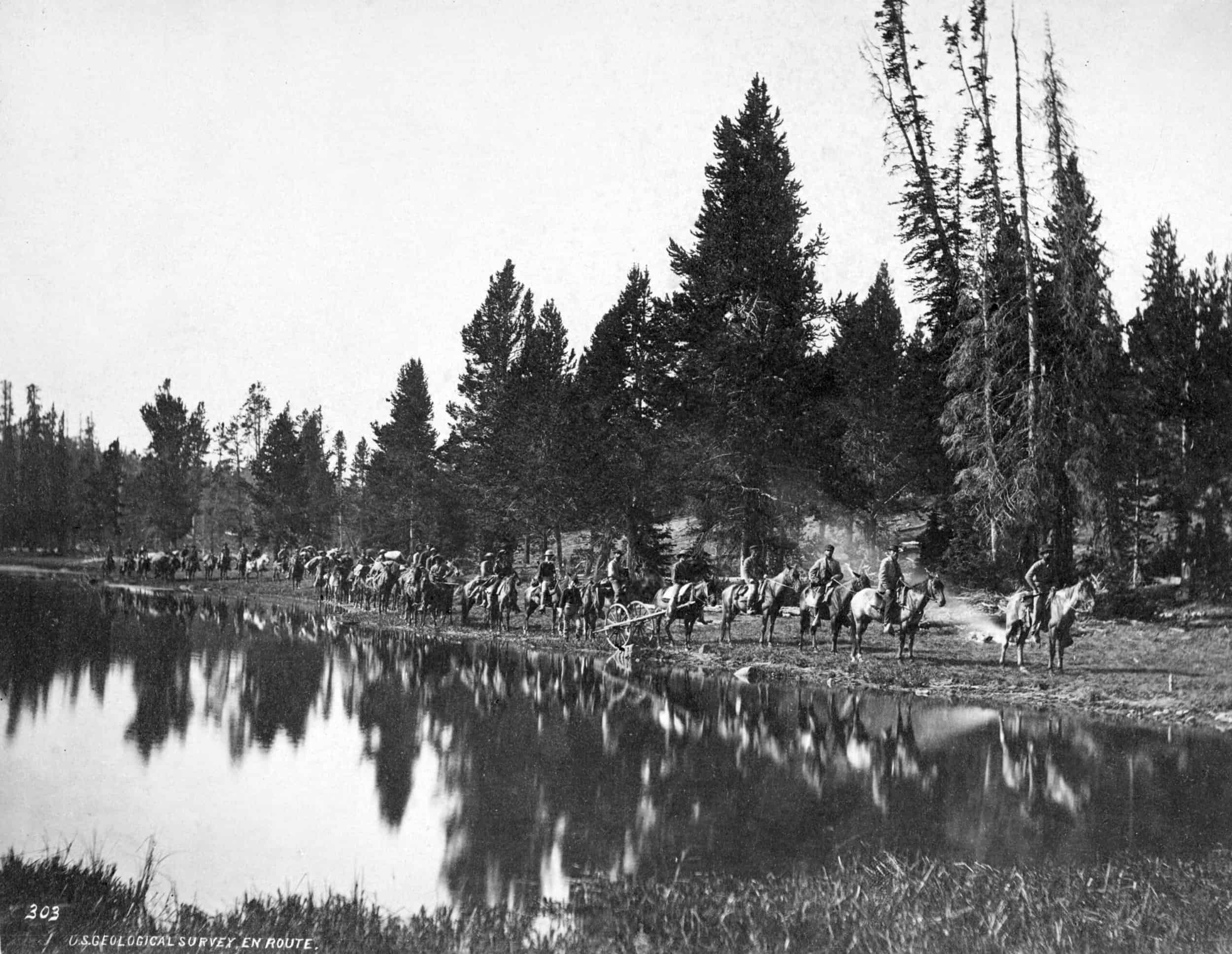

These details, jotted into daily journals, were left by crew members prepping for a six-week-long journey into modern day Yellowstone. Many of the men were experts in their fields—the first cohort of artists and scientific thinkers to document the geology, fauna, meteorology, and vistas of Yellowstone. (Of course, generations of scientists have followed in their footsteps.) Although the Hayden Expedition was the third organized expedition to the region in three years, the vigorous record keeping and amassing of detailed data that came out of the survey were firsts.

“They even took the depth of Yellowstone Lake, which was an enormous project,” says historian and author Marlene Merrill, an eighty-eight-year-old chronicler of the Hayden Expedition. “None of this had been done before: The height of the mountains, the temperatures of the geysers—it was a very wonderful scientific overview of what was there.” The precise information was important (they even rolled odometer wheels to determine distances), but just as influential to history was the presence of crew members who could depict to the American public what would prove iconic views. William Henry Jackson’s photos and Henry Wood Elliot’s and Thomas Moran’s landscape paintings brought otherworldly geyser basins and the dramatic chasm of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone to anybody who wanted to see it. Their work was also the beginning of an enduring tradition. “One of the legacies of the Hayden Expedition is this concept that art is important to national parks,” says Yellowstone National Park staff historian Alicia Murphy. “Because those men were along and shared their imagery, that not only created the park, but it also created that tradition of art in what would become the entire Park Service.”

High in Hayden’s mind was completing the mapping of all tributaries feeding into the Yellowstone River and Yellowstone Lake – a goal he accomplished and documented in his reports.

It’s well established that Yellowstone’s creation was a direct result of the Hayden and its two forerunner expeditions: the 1869 Folsom-Cook-Peterson Expedition and 1870 Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition. Before these, there was a lengthy history of humans in the area—about 11,000 years of Native American use, including year-round occupation by the Tukudeka, AKA Mountain Sheepeater band of Shoshone. White fur trappers and mountain men also visited Yellowstone and the surrounding mountains and valleys every year starting in approximately the 1820s. But any documentation the Natives produced hadn’t been uncovered or was poorly understood, and the lore of the trappers was viewed as hearsay. “People were coming through here, but trappers were not the most reputable members of society,” Murphy says. “They tended to tell a lot of tall tales, and it was kind of hard to know what the truth was.”

That all changed with the Hayden Expedition and the reports that came out of the government-sponsored survey, which had a $40,000 budget. Water really shot out of the ground. Subsequently, the push to create Yellowstone happened in a flurry. Hayden and businessman Nathanial Langford, of the Washburn Expedition, lobbied hard and were intent on turning Yellowstone into something that would prevent the area from being developed and exploited. The construct—a national park set aside for the benefit and enjoyment of the people—was unheard of at the time. “That’s why it’s the first,” Merrill says. The remote, high-elevation Yellowstone region was not particularly valuable for agriculture or mining, which supported the argument that the government risked little financially. And so, lawmakers went along with it. “The reality is nobody really cared,” says Moose resident and historian Bob Righter, a scholar of neighboring Grand Teton National Park. “Yellowstone mainly came about because there was no opposition. There was no great debate about Yellowstone.”

Congress passed the legislation creating Yellowstone just six months after Hayden and his crew completed the expedition. There was no discussion about the bill in either legislative branch, and President Ulysses S. Grant promptly signed it into law, Murphy says. The protected park that resulted covered 3,344 square miles—96 percent of modern-day Yellowstone’s expanse—and it was created just in time. In early March of 1872, entrepreneur Matthew McGuirk filed a claim for 160 acres where Mammoth Hot Springs runs into the Gardner River with plans to develop a commercial “medicinal springs.” It never happened though, according to Merrill’s 1999 book Yellowstone and the Great West. “Unknown to McGuirk, the land had been withdrawn from the public domain only eight days before he filed his claim, when President Grant signed the Yellowstone Park Bill into law,” she wrote. “The creation of the world’s first national park had come none too soon.”

The expedition did not always move as one group, instead breaking off into teams at times to fulfill disparate duties.

On the ground, the expedition team moved via horses and mules and was forced to abandon its wagons because of rough terrain after Bottlers Ranch on the Yellowstone River, outside the present park. High in Hayden’s mind was completing the mapping of all tributaries feeding into the Yellowstone River and Yellowstone Lake—a goal he accomplished and documented in his reports. Lacking from the formal reports, but well documented in the hand-written journals, are the hardships of the endeavor. To the delight of Hayden, none of his thirty-some expedition members died, though some became lost for days and there were injuries and bouts of illness. At times, there was little more to eat than small game like grouse, duck, and rabbits. For Merrill, a fascinating part of her scholarly inquiry into the Hayden Expedition was reading of Yellowstone’s splendors through the lens of people like geologist Albert Peale, who was seeing these features for the first time. Often, they were in awe. “What I particularly liked was the human reaction to a place that is so beautiful,” Merrill says. “There’s something absolutely powerful about being in that area and realizing its history.”

Peale’s journal entry from July 27, 1871 conveys that sense of wonder in vivid detail. That day—a Thursday—began with a scramble down to the base of the Lower Falls of the Yellowstone, a feat that hunters and trappers had told him could not be done. With Henry Wood Elliot at his side, the duo reached the bottom after an hour and fifteen minutes of downclimbing. “The cañon is grand,” wrote Peale, who marveled at a rainbow in the mist and iron-stained rock walls. “Along the banks, from top to bottom, the river rushes through the narrow space at the bottom as if chafing against its imprisonment.” Later that day, they rode into Hayden Valley, breaking at Dragon’s Mouth Spring (“a delightful place for a vapor bath”) and Mud Geyser, which they gazed upon as its agitated, geothermally heated turbid waters were flung ten feet into the air. “We returned to camp wondering what wonder this country will produce next,” Peale wrote that evening.

Who Were They?

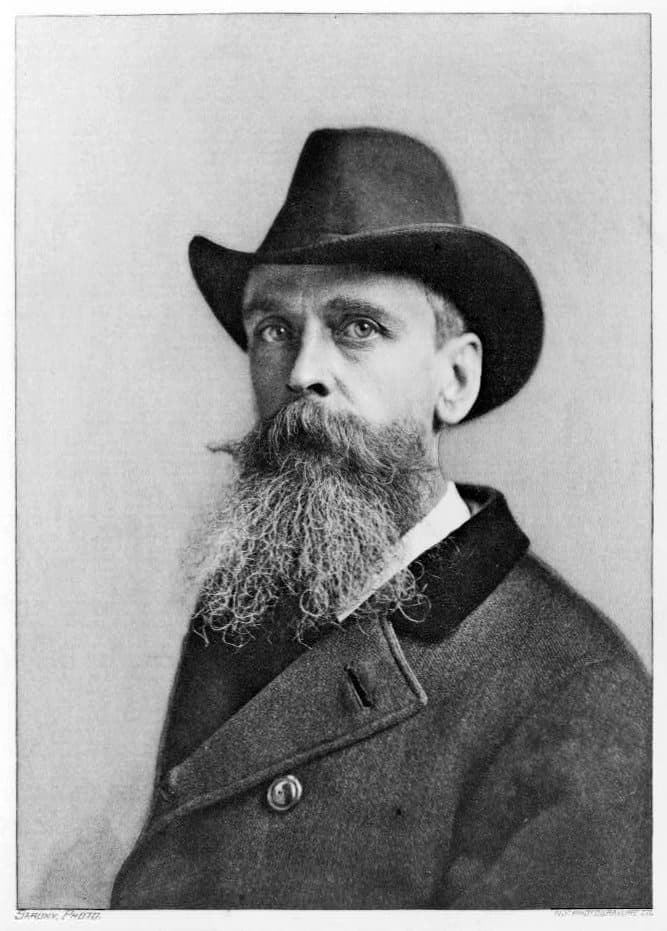

Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden is the expedition’s namesake, and the geologist, physician, and Civil War veteran was the most famous of the thirty-some-odd expedition members (the number varied throughout the trip). By 1867, Hayden was a veteran surveyor of the West who had been appointed the geologist-in-charge of the U.S. Geological Survey. Although crew members were trained in botany, zoology, meteorology, and other disciplines, most participants were not well-known. Some were hunters, cooks, and working stiffs who tended to the mules. The expedition even had a waiter. Partly, the crew members were anonymous because they were young, most in their twenties. Some were the sons of political figures upon whom Hayden depended for funding, and so got to go because of their families’ connections. There are some exceptions though; here are some snapshots of notable members of the Hayden Expedition, gleaning information from Marlene Merrill’s 1999 bookYellowstone and the Great West.

The oldest member of the survey crew, George Allen was brought on as a botanist through a connection to Hayden—Allen had been Hayden’s professor at Oberlin College. “He never made it into Yellowstone,” Merrill says. “He left the survey just as they were north of Yellowstone, just because he was too old. That’s always tickled me, because he was in his fifties—and that doesn’t seem to be that old.” Allen’s journals provide some of the best insight into the expedition before the party entered the park.

TRIVIA: George Allen was married to Caroline Rudd, one of the first three women in the U.S. to receive a college degree.

Hayden’s official expedition photographer for all of the 1870s, William Henry Jackson provided the earliest photographic record of the Yellowstone territory. His images helped persuade Congress to set aside as a national park a place they had never seen. After his expedition days, Jackson settled in Denver and opened a photography studio, though he later moved to Detroit, to Washington, and finally New York. Jackson lived for nearly a century, even returning to Yellowstone as late as 1941, at age ninety-eight. The occasion? He attended the celebration of the designation of the Jackson Hole National Monument, the predecessor of the enlarged Grand Teton National Park.

TRIVIA: Jackson is the great-grandfather of American cartoonist Bill Griffith, who created the daily comic Zippy.

A landscape artist made famous through his role in the 1871 Hayden Expedition, Thomas Moran took a serious liking to the place—so much that he began initialing his work “TYM,” for “T. Yellowstone Moran.” TYM went on to travel and paint throughout the American West, depicting scenes of the Yosemite Valley, southern Utah and Arizona, and central Colorado’s Mount of the Holy Cross. “His work was, and is, seen as the definitive treatment of these scenic wonders,” Merrill writes.

TRIVIA: Moran’s famous painting The Grand Cañon of the Yellowstone wasn’t completed until two months after the Yellowstone bill was signed into law. It was unveiled at a private party in New York City that was funded by Scribner’s.

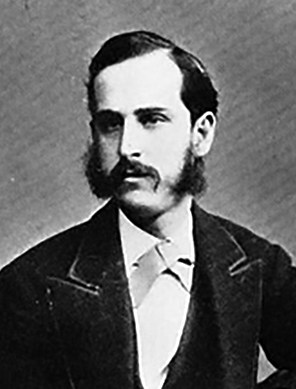

Albert Peale was just getting to know Ferdinand Hayden during the 1871 Yellowstone Expedition, though they went on to become close friends and colleagues on a number of expeditions that followed. A field geologist, Peale published his writings in Hayden’s annual reports.

Peale’s diaries were cataloged in two different repositories and had never been stitched together until Merrill dug them out of archives. “It took me twelve years to do this,” she says. “It was a labor of love.” Merrill was thrilled to see that the Peale narrative began just as the party headed into Yellowstone, picking up right when Allen’s journals were no longer documenting the expedition.

TRIVIA: The U.S. Geological Survey named a number of features in the West after Peale, including the most southerly island in Yellowstone Lake, the highest peak in eastern Utah’s La Sal Mountains, and a mountain range in eastern Caribou County, Idaho.

Charting a Pre-Yellowstone Route

Time wise, just a third of the 1871 Hayden Expedition was spent within the modern boundaries of Yellowstone National Park, although exploration of that area was always the prize.

The party departed in early June from Ogden, Utah, then traveled north, passing through what would become Idaho Falls and then up the Henry’s Fork drainage until it crossed over the Continental Divide inato Montana at Monida Pass between the Centennial and Beaverhead Mountains. By mid-July, the survey party had resupplied at Fort Ellis near Bozeman and was pushing south up the Paradise Valley toward the park. The route was unable to accommodate wagons, and so the party set a base camp near Bottler’s Ranch (across the river from what is today Chico Hot Springs).

In its six weeks in Yellowstone, the Hayden Expedition entered the park around Mammoth Hot Springs, headed east toward Tower Falls, then continued past the falls to survey around Mount Washburn. The expedition did not always move as one group, instead breaking off into teams at times to fulfill disparate duties. By the closing days of July, parts of the survey team were exploring Yellowstone Lake via a makeshift vessel, the Annie, while other parts of the crew pointed west toward the Firehole River drainage to document the park’s largest concentration of geyser basins.

The middle of August was spent mostly on the south and east sides of the park, where the expedition mapped the Yellowstone River’s headwaters and the Lamar River. The group was at the latter when a series of earthquakes shook the ground. The voyage through Yellowstone itself was all wrapped up by the last week of August, when the party departed via Mammoth and Gardiner on its way back to Bottler’s Ranch and then Fort Ellis. Over the month of September, the group continued moving south, both backtracking in places and charting a new route. The terminus was southwestern Wyoming’s Fort Bridger, where Hayden officially called his 1871 Yellowstone expedition a wrap.

Relive the Hayden Expedition Today

Photographer Bradly J. Boner’s 2017 book Yellowstone National Park: Through the Lens of Time recaptures dozens of vistas immortalized by William Henry Jackson in 1871, when Jackson first brought photography to Yellowstone. Conducted more than 140 years apart, the two photographers’ tasks were wildly different. “It definitely gave me an appreciation for what they did,” says Boner, who is Jackson Hole magazine’s photo editor. “Obviously, I was able to zip around the park in a car to a lot of the places that they got to with horses, ponies, and pack mules.” It wasn’t all easy, however, and exploring to find the exact locations where Jackson stood well more than a century before proved to be an adventure. Those photo points took Boner into the backcountry canoeing around Yellowstone Lake and backpacking off trail through the seldom-visited Mirror Plateau. Others images were taken near famous overlooks that still were tricky to find. “I got it wrong a couple of times, and I hiked a lot of miles out of my way that I didn’t have to,” Boner says. “It really gave me an excuse to explore parts of the park where I never would have gone, and that in and of itself was an unforeseen gift and a real pleasure.”

Boner’s book, which was published in 2017, shows that Yellowstone’s landscape is largely unchanged. Most major differences that are detectable were driven by natural processes like erosion, wildfire, and blowdowns. For the most part, Hayden and others who sought for the park’s protection got what they wanted. “The whole idea of the creation of Yellowstone was preserving it for future generations,” Boner says. “Looking at these photos from 1871 and looking at them from today—more or less it’s working.”

Boner’s book is out of print, though it still can be purchased as an e-book. Another option to learn more about the Hayden Expedition this summer is to look to Yellowstone’s Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter pages. Alicia Murphy, the park’s historian, will post daily about what the survey team was doing the same day 150 years before. JH