Read The

Current Issue

Jackson’s Whole History

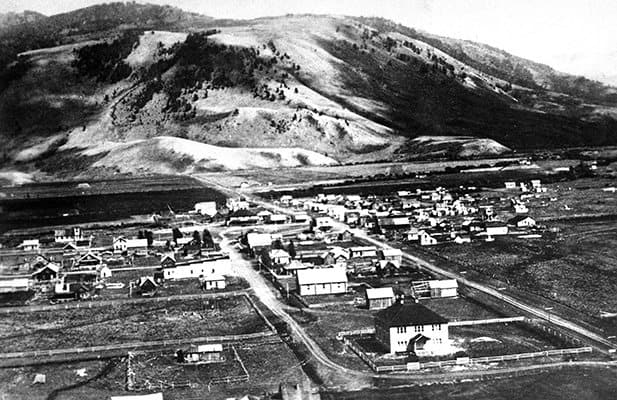

Birth of Town Square – Celebrating 100 Years – Historical Walking Tour of Downtown

BY RICHARD ANDERSON

The Teton Range, geologists say, first sprouted about 9 million years ago. The Yellowstone Caldera, which sculpted so much of the landscape we know today, last exploded some 600,000 years ago. Archaeologists have found evidence of human habitation in the Jackson Hole area dating back perhaps 11,000 years. By comparison, the Town of Jackson’s 100-year history is a blink of the eye. But what a 100 years it has been.

The first permanent settlers arrived in Jackson Hole—and let’s clarify that the entire valley is Jackson Hole; Jackson is the main town—in 1884, six years before Wyoming became a state. For many years, it could take a full day of hard riding for one valley resident to visit another. The following year, Robert Miller brought the first wagon over Teton Pass. By 1888, the population of the valley had hit twenty-three.

In 1893, Miller brought his bride, Grace Miller, to the valley. At first, they lived in a log shack supposedly abandoned by an outlaw known as Teton Jackson, but within two years, they began to build a home on what is today the National Elk Refuge. That home—surprisingly comfortable and well-appointed for a frontier homestead—still stands and is open to visitors during the summer (see p. 28 for more).

In 1897, Grace bought some land toward what was called Simpson’s Ridge and is today the Snow King Ski Area. She had the idea it would make an ideal town site. That same year, members of the Jackson Hole Gun Club built The Clubhouse, which served a variety of needs: a meeting space, dance hall, courtroom, smoking club, gymnasium, and, later, a schoolhouse. The Clubhouse still stands; it’s on the east side of the Town Square and houses several shops and, upstairs, offices.

A hotel came in 1901, the year Bill Simpson (Sen. Alan Simpson’s grandfather) laid out the first town plat for Jackson, which, like all of western Wyoming, was still part of Uinta County. Mormons built Jackson’s first church in 1905 on the west end of town, and Fred Lovejoy established the first telephone exchange. Frank and Roy Van Vleck were headed from Colorado to Oregon with a wagonful of produce in 1906 when sick horses stranded them in Jackson. They ended up selling their wares and opened the Jackson Mercantile, the town’s first general store where one could buy everything from building materials to sacks of flour.

Pioneers, of course, settled elsewhere throughout Jackson Hole, forming communities such as Cheney, Elk, Zenith, Grovont, Wilson, and Kelly (which, in 1923, gave Jackson a run for its money to become the county seat after Teton broke away from Lincoln to become its own jurisdiction). But as Virginia Huidekoper observed in her book, Wyoming in the Eye of Man, Jackson “was a natural crossroad linking all ends of the valley,” and it proved itself as the social and cultural hub of the Hole.

By 1914, the village’s population had swollen to about 200. The town newspaper, Jackson’s Hole Courier, which was founded five years earlier by Douglas Rodenback, ran advertisements for Simpson’s Jackson Drug, C.J. Wort’s livery and feed stables, the Elk Cigar Store, two hotels, a blacksmith, dentists, attorneys and, in the August 20, 1914, edition, this notice: “The new bank opened its doors Wednesday, and is now doing business.” This wasn’t just any bank, but The Jackson State Bank, which survived until Wells Fargo bought it in 2008.

Incorporation was the next logical step, and the question was called September 21, 1914. The Courier printed the results of the vote a few days later: 48 to 21 in favor. The Town of Jackson was born. To this day, Jackson is the only incorporated municipality in the county.

Women Rule!

Meet Jackson’s ‘Petticoat’ Council

Among the first orders of business for the newly incorporated town was the election of officials. This happened, in The Clubhouse of course, on November 28, 1914. The results, announced in a brief item in the December 3 Courier, were Mayor Harry Wagner and councilmen C.J. Wort, Chester Simpson, H.W. Deloney, and J.H. Jones.

It didn’t take long—by 1916—for there to be grumbling that the town’s business could be conducted better. Taxes were not being collected, and fines were not being paid. There was only about $200 in the treasurer’s account. In the spring, the town’s dirt roads were veritable rivers of mud, with no ditches or culverts to carry water away. And while Jackson Hole’s reputation for lawlessness was probably overblown in the papers of the region, not all town ordinances were strictly enforced. Who was up to the task of cleaning up this dirty little frontier town?

The answer came in 1920, the same year the 19th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution was ratified, prohibiting any U.S. citizen from being denied the right to vote because of gender. (Of course, Wyoming, in 1869, decades before it was even a state, had earned its nickname “The Equality State” by granting women the vote; the following year, it appointed the country’s first female justice of the peace, Esther Hobart Morris.)

In April 1920, Jackson citizens nominated an all-female Town Council ticket. (Oskaloosa, Kansas, and Kanab, Utah, had both already elected all-female Town Councils in 1888 and 1912, respectively; however, Jackson’s all-women government was unique for a reason we’ll get to later.)

On the ticket were, for mayor, Grace Miller; for two-year councilmen—“or rather councilwomen,” the Courier demurred—Rose Crabtree and Mae Deloney; and for one-year terms on the city council, Genevieve Van Vleck and Faustina Haight. “We consider this a representative and very capable ticket and predict for Jackson a very excellent and beneficial administration if the ticket is elected,” the Courier wrote.

All the nominated women were members of the “Pure Food Club,” a social group whose meetings were closely covered by the newspaper. Sue Schrems, a historian and author of the blog WesternAmericana2, notes that Pure Food Club might have been “a misnomer for a card club where the ladies played poker and enjoyed an afternoon of culinary delights.”

Citizens also nominated an all-male lineup, to give the ladies some competition: For mayor, Fred Lovejoy; for two-year councilmen, Henry Crabtree and William Mercill; and for one-year councilmen, M.E. Williams and T.H. Baxter.

The election of May 11 garnered national headlines, not the least because of the spousal contest between Rose and Henry Crabtree. The results weren’t even close. The women won by a wide margin, in some cases by nearly 2-1.

“Husband defeated by wife,” a New York Times headline from May 1920 declared. “Their complete victory surprised even the women themselves,” the Courier reported on May 13. “For the next two years Jackson will, if the women fulfill one-half of the prophecies made by leading papers of the United States, enjoy and benefit from one of the best administrations she has ever known.”

No lesser eminence than Calvin Coolidge, who at the time was governor of Massachusetts, even praised the Jackson electorate for their “good sense.”

The women took office on June 7 and quickly got to work. Among their first acts was to make appointments. These, too, were women, which is what made Jackson Hole’s “Petticoat Government” especially noteworthy. Edna Huff was appointed health officer, Marta Winger was named clerk, Viola Lunbeck was treasurer, and twenty-two-year-old former soda squirt Pearl Williams was named town marshal.

Williams in particular caught the attention of the national press. The Courier reprinted part of a hilarious 1921 interview conducted by a correspondent of an “Eastern newspaper” that, supposedly due to the primitive phone exchange, had to be patched through from Chicago to Cheyenne, then to Salt Lake, then to Pocatello, then to St. Anthony, Idaho, where the operator relayed questions onto Jackson for Williams to respond to.

“Folks, meet Pearl Williams,” the piece begins, “the world’s champion wild man tamer. Pearl, be it known, is the little lady who, as town marshal at Jackson, Wyo., for the past year has been subduing bad men with smiles. … For more than 30 years Owen Wister and numerous other press agents for the west, have made Jackson’s Hole, of which the town of 526 souls is the center, the incarnation of all that’s wild and wooly and thoroughly western. That is, they did until Pearl became marshal.”

The interview appeared to be a tiny bit too late, however, as Williams had already resigned from the job.

Correspondent: “Why did she resign?”

Operator: “She says the town is now so quiet it don’t need no marshal any more [the grammatical error, it was concluded, was the operator’s not the marshal’s].”

Correspondent: “Please ask her if it is not true that the town has no jail and that the county jail is nearly two hundred miles away. Ask her how many arrests she made during her year’s term, and what she did with the men she arrested.”

Operator: “She says she didn’t make any arrests, and so didn’t have to go hunt up a jail. She says that a while ago she killed three men and buried them herself and that she hasn’t had no trouble with anybody since.”

In May 1921, Miller, Van Vleck, and Haight ran for re-election. This time, their margin of victory over their male opponents was better than 3-1.

“Considering the fact that Mr. [Walter] Spicer, who was ‘run’ for mayor, and Messrs. [Almer] Nelson and [George] Blain, who were boosted for Councilmen, are all three well known and very popular citizens,” the Courier announced, “we interpret the election returns to be a complete vindication of the women’s past record.”

Growing Up With Jackson Hole

Being snowed in from November to May.

Traveling to Victor, Idaho, in the fall to meet the train and lay in a winter’s store of staples.

Heading into Jackson once or twice a year.

These are just a few things Marjorie May Ryan remembers from her childhood. Ryan was born in July 1934 in the town of Grovont, Wyoming, on what today is better known as Mormon Row, north of Kelly. She and twelve or fifteen other Grovont kids went to a one-room schoolhouse through eighth grade. She knew everyone in the tiny town of a dozen or so families, and everyone knew her. Working hard, making your own fun, and gathering together as a community for the occasional dance were the facts of life for the children and grandchildren of Jackson Hole’s homesteaders.

Ryan’s parents were Clifton and Fay May. “My great-grandfather came in 1894 and homesteaded,” she says. “My grandfather, when he was fifteen, came from Rockland, Idaho. My father was born March 10, 1905, and I was born in the same house. … They were all ranchers.”

“People ask me if we were poor,” she says, sitting to chat in her home on Redmond Avenue, surrounded by a lifetime of memories and memorabilia. “I don’t remember being poor. We had food and clothes. We weren’t rich … but everyone was the same way, it was not like you had class distinctions. We had a good time, we worked hard, and we played, too.

“My folks did not have electricity or running water until 1954. They raised nine children without it.”

Folks would do whatever they could to make an extra dollar back then. In addition to cattle, Ryan’s father raised sheep. He also was a talented musician, Ryan says. “My dad had a dance band. Every dance I went to when I was growing up my dad played. In the summer, he would go to dude ranches to play to make extra money. That was during the late ’30s and 40s. … When I was born, my dad was playing a dance. Dr. Huff was at the dance, and they had called so he left to come deliver me, but by the time he got there I was born, so he came back to the dance and as he danced by the band, he said, ‘It’s a girl.’ ”

For the most part, Grovont kids had to make their own fun, but once in a while they would make it into town. “In summer, my mother would come in [to town] maybe once a week. Occasionally I’d get to come in for a movie at the Rainbow. The Rainbow is where Ripley’s Believe It or Not is now. My cousin, Thora May, lived upstairs of the theater, and we’d roller skate in the park by the Episcopal church, which was the only park that was paved. I wouldn’t come to town more than a couple times a year.”

Ryan’s husband was John Ryan. He died in 2007. “He started work at Jackson Drug when he was in high school, in the summers and after school. He worked and managed it until 1979, when we sold [our shares in the business]. His mother was Ben Goe’s daughter [Goe was the owner of the Cowboy Bar], and his father came down from Montana. Johnny was born in July 1932. His father died that August,” she says.

“I came to town for high school in the winter of 1949-50, and we had to board then. I met John in school. We married in July 1951. I was seventeen, and he was nineteen. We got married at 8 a.m. on Tuesday—that was John’s day off—and we took off Wednesday, and he had to be at work at 1 p.m. Thursday. That was the size of our honeymoon.”

Later that year, they moved into the house on Redmond. “When John and I married, he’d already bought this property from his aunt and uncle. We built the little house on the corner. A few years later, we had three kids so we built this house. … When we first moved out here we were in John Hall’s hayfield. There was nothing here—no electricity, no water. We moved here in July, and it was October before they got power out to us. That was in 1951. It was 1954 when we got water.

“We had four kids,” Ryan says. “They all still live here: Terry Schupman works for the city, Patricia Randall worked in the treasurer’s office, John C. Ryan works for the city in the water department, and Kelly Ryan, our youngest, is in the ER in the hospital.”

The Birth of the Town Square

The front page of the April 29, 1920, Jackson’s Hole Courier included this item:

“The work of cleaning up the public square in Jackson was resumed again yesterday. Louis Curtis and Ray Golden are doing the work, using a Fordson tractor and a ‘Fresno.’ ” Jackson didn’t seem to care, or, if it did, didn’t acknowledge it was creating something Wyoming had never before seen: a public town square.

The “public square” had for decades been little more than a hollow into which early Jacksonites threw their construction debris as they worked on The Clubhouse, The Jackson State Bank, JR’s Saloon, Jackson’s post office, and the other buildings that would form the heart of downtown. On cold winter nights (there were plenty of those, including a memorable string of 50-below days in the early 1920s), cattle might huddle there to share heat.

Photographs from the first decades of the twentieth century show an open area dotted with scrubby sagebrush. It might not have been much to inspire civic pride, but in 1917, the town gained title to the land. They graded it and the streets that surrounded it, and citizens began to use the square for Flag Day observations, Christmas tree displays, and rodeos.

In April 1920, Teton County veterans of World War I founded American Legion Post 43. One of the earliest posts in the country, it counted among its members such prominent citizens as Homer Richards, Olaus Murie, and a long list of Ferrins and Linns and Cheneys. They built a hall at the corner of Gill and North Cache and, as a service project, set to work improving the square. They raised $150 and removed some of the old waste (who knows what archaeological curiosities still lurk beneath the square?), planted trees, and built a fence to keep the cows out.

In the early 1930s, the town got serious and did more substantial landscaping. With help from Depression-era public works programs, they roughed in the paths that make an X through the square and raised a monument to the valley’s veterans in the center. In 1932, in honor of the bicentennial of the birth of the country’s first president, they named the square George Washington Memorial Park.

The more construction that took place around the square—a dentist’s office, Jackson Drug, a butcher shop, Moore’s Cafe—the more it became a social hub. Historic photos show parades streaming down Cache and Broadway past the square and, in the winter, early versions of the Cutter Races sent two-horse chariots screaming by. One panoramic image captures as many as one hundred people, including high schoolers from Gillette, gathered during a Lions Club convention in 1936. In 1939, the dedication of the John Colter Memorial, on the west side of the square, was attended by Mayor Harry Clissold and Gov. Nels Smith.

In 1953, Jackson Hole’s Rotary Club began its first elk antler arch on the southeast corner of the square. By 1969, all four corners boasted the decoration—each of which required up to 10,000 pounds of antlers—beneath which countless millions have had their photographs taken. In 2007, the club once again began to amass antlers to rebuild the aging arches. The last one was rebuilt in 2013.

In 1959, a log home that belonged to Charles Wort (of Wort Hotel fame) was placed on the southwest corner and became known as the Stage Stop, a place to dispense information and, more recently, the headquarters of a stagecoach ride concession that takes folks on a pokey little circumambulation around the northeastern quadrant of downtown. The original shack was replaced in 1995.

These days, the Town Square is unmistakably the heart of downtown Jackson. Parades roll past grandstands on the square for Memorial Day’s Old West Days and the Fourth of July. Thousands of twinkling lights bedeck its trees—all of which have been planted over the years—for Christmas, and the Lighting of the Square is the traditional start of the holiday season in Jackson.

Since June 1956, hundreds of summer tourists have gathered near the northeast corner for the Jackson Hole Shootout, the country’s longest-running Wild West massacre that takes place six nights a week. And since 1968, hundreds of small children have braved iffy spring weather for the annual Easter Egg hunt, which used to be put on by The Jackson State Bank and now is run by Wells Fargo.

That year also marked the first Jackson Hole Boy Scouts Elk Antler Auction, an event that attracts furniture makers, jewelers, traditional medicine crafters, folks with elk-antler-arch envy, and the plain old curious from all around the world to admire and, if the spirit moves them, bid on antlers. The auctioned elkhorn (actually made of bone and shed annually by the beasts) are gathered earlier by the Scouts from the National Elk Refuge as a service project. Most of the proceeds go back to the refuge to benefit its 8,000-some-strong wild herd; 20 percent, however, funds Scouting in the Tetons. In recent years, the auction has turned into a weekend packed with a private antler sale, food court, community band concerts, Scouting expo, historic demonstrations, educational booths, and Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation’s annual fundraising banquets.

And the square continues to find new uses. The Jackson Hole Farmers Market is in its eleventh year there. It’s a logical place for Fall Arts Festival events such as the Art Association’s Takin’ it to the Street art fair and QuickDraw art show and sale. It has also served as the center for a Japanese Fire Festival, imported to town by the nonprofit Vista 360 and including Japanese food, drumming, arts and crafts, and a torch-building and -lighting ritual that thanks firefighters and appeases the spirit that resides within the fiery bowels of the greater Yellowstone area. For the past couple winters, a group of skating enthusiasts has been allowed to create an ice rink on the west side of the square, and couples, families, and groups of friends enjoy hot chocolate, the twinkling winter lights, and the outdoor, in-town ice.

While the Town Square and its environs have changed over the years, one thing hasn’t: It’s still the only town square in the state. JH