Read The

Current Issue

A Gros Ventre Escape

For nearly 125 years, Flat Creek Ranch has voffered a hidden retreat.

// By Jim Stanford

Farney Cole didn’t hear a twig snap. As he bent down to dismantle a beaver dam that was inundating a hay meadow on upper Flat Creek in August 1944, the first indication of trouble was the scratch of claws on his neck.

A sow black bear attacked him, slapping and biting him on the shoulders as he fell to the ground. Later estimated to weigh 600 pounds, the bear had two cubs and had been frequenting the ranch for several years, losing its fear of humans. Cole, a squarely built Kansas native and experienced cowboy, played dead, and the bear relented. As it moved away, Cole reached for a five-foot-long, waterlogged aspen limb he had been using to break up the dam. When the bear charged to attack again, Cole whacked it in the head with this makeshift club and stunned it. Then he beat it until the bear was dead.

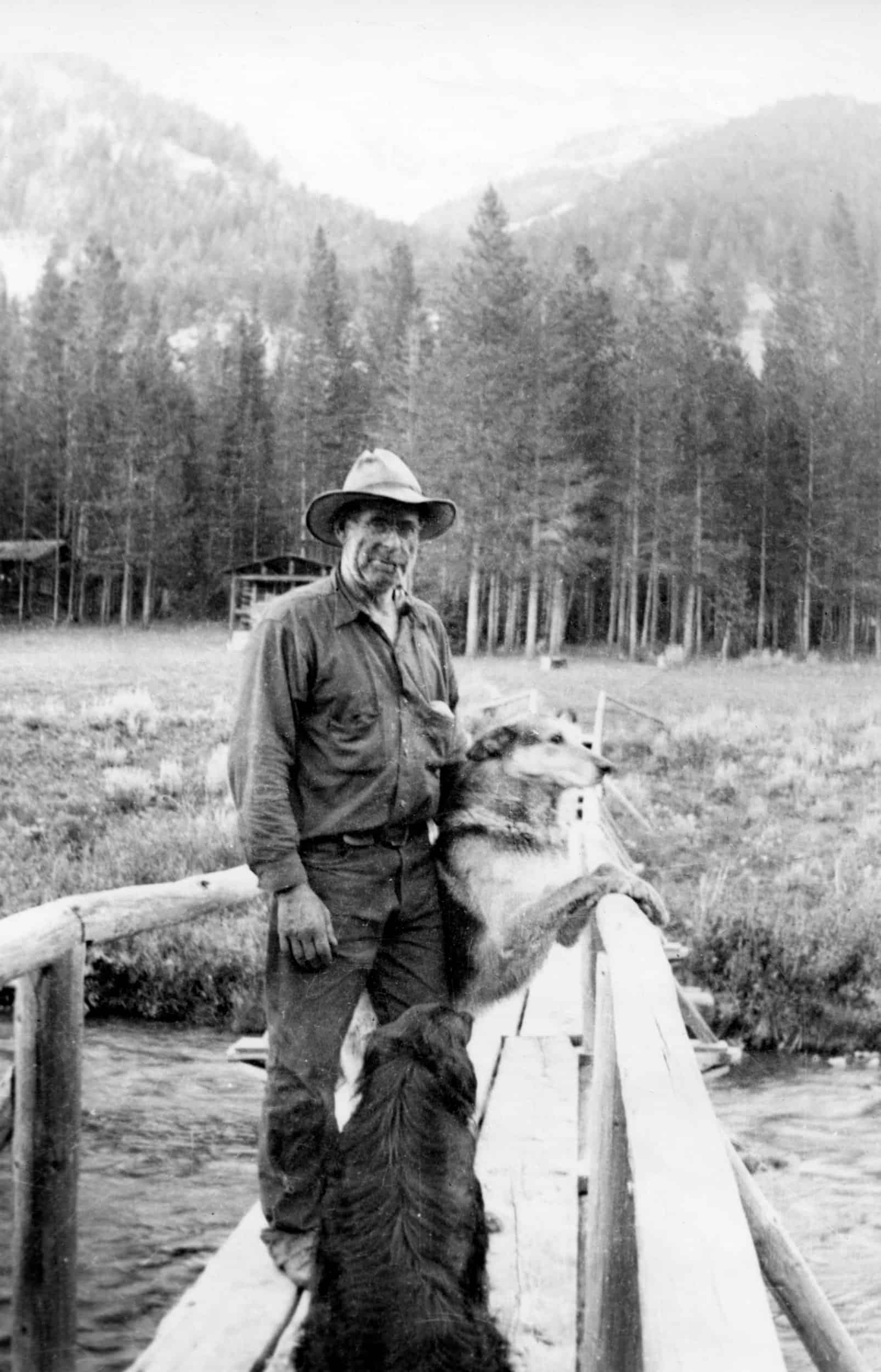

He later told the Jackson’s Hole Courier he didn’t want to kill the bruin but never would have felt safe there again. And besides, he said, “she made me mad.” An Associated Press story about the attack made newspaper headlines across the country, earning Cole marriage proposals by mail. He was treated at the hospital for his injuries but was back on his feet in no time, and upon his death in December 1963 at 79 years old, his obituary in the Jackson Hole Guide referred to him as “last of the mountain men.”

The famous bout is but one small chapter in the long and storied history of Flat Creek Ranch, the 140-acre hideaway tucked into a narrow canyon in the Gros Ventre Range below the head of Sleeping Indian. The ranch is only 14 miles from Jackson, but, sequestered inside the national forest atop one of the roughest roads in Teton County, it sits a world apart. It is the setting for one of Jackson Hole’s most celebrated romances, a rumored horse-thief hangout, a haven for hunters and outfitters, a brief gambling outpost, a fishing retreat for politicians and celebrities, and for the last 22 years, a family-vacation destination.

Indigenous people may have used the area to hunt, but Orestes St. John, staff geologist for the Hayden Survey expedition of 1877, was likely the first white man to lay eyes on the site when he climbed Sheep Mountain and peered down on a “gorge-like valley.” In the summer of 1900, cowboy Enoch “Cal” Carrington would camp there for four days while working as a cook on a hunting expedition. Smitten with the place, Carrington returned the following summer, quietly built a small cabin, and squatted on the land.

The secluded valley remained a secret for nearly two decades, during which time it may or may not have harbored stolen horses, until Carrington and Eleanor “Cissy” Patterson began building more cabins. The two had met in 1917 at the Bar BC Ranch, where Patterson was a guest and Carrington the head hunting guide, and quickly forged an intimate friendship. Carrington received the patent for a homestead in 1922 and sold the property to Patterson in 1923. “Never in my life anywhere have I seen anything lovelier than this place,” she later wrote to her brother.

Also known as the “Countess Gizycka” after a failed marriage to a Polish count, Patterson was a socialite and heiress to the Chicago Tribune publishing family but also a strong outdoorswoman who could ride and shoot. Much has been written about her and Carrington, who traveled to Europe together and may or may not have been lovers. In 1928, she hired Cole to be caretaker of the ranch, and he spent the next 20 years up there, trapping through the winter and occasionally making the journey to town on skis, until her death in 1948.

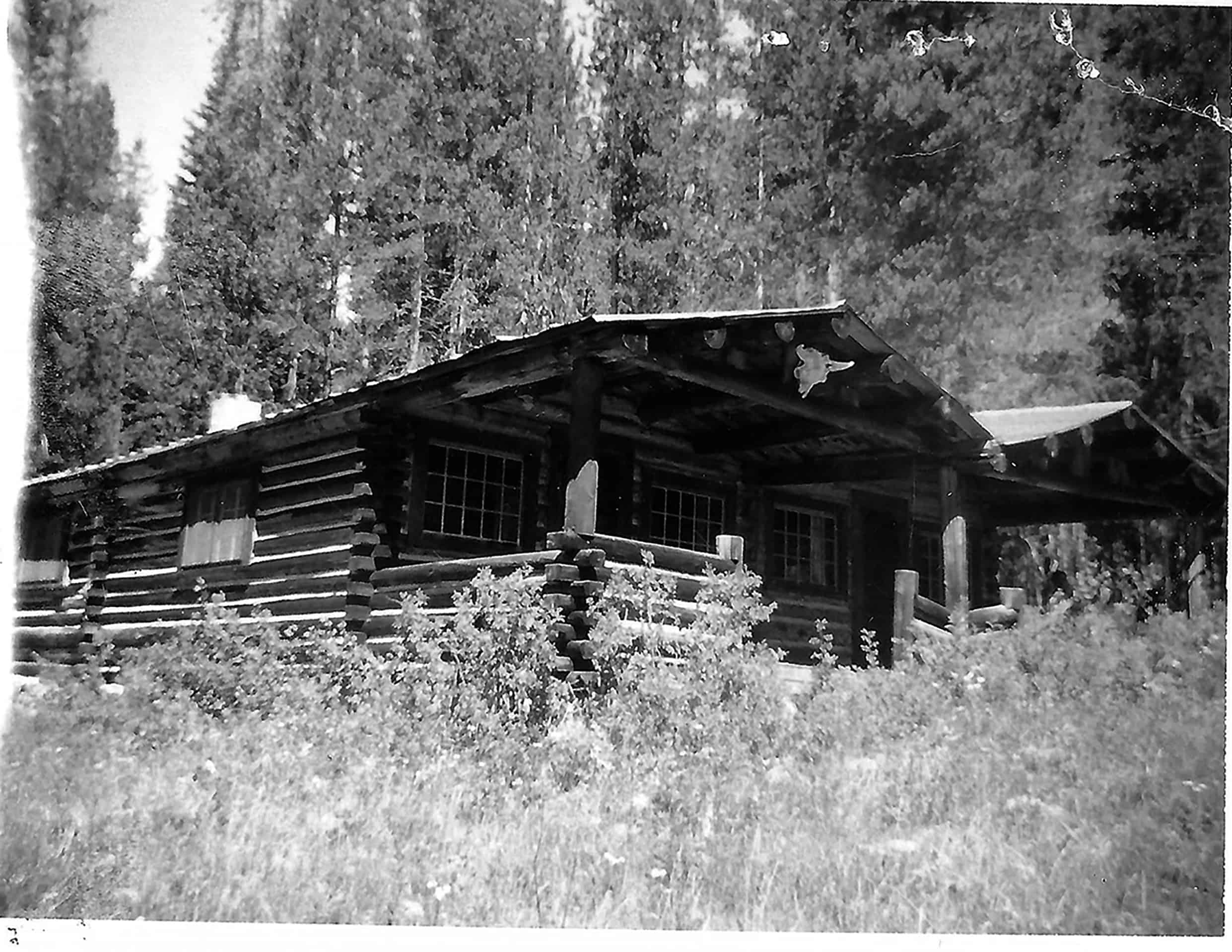

In 1998, after a succession of transfers and leases that saw the ranch pass to Patterson’s niece Josephine and then to the Jackson Hole Land Trust, Patterson’s great nephew Joe Albright bought the property. He and his wife, Marcia Kunstel, both veteran journalists, set about an ambitious restoration that lasted four years and was headed by renowned craftsman Porgy McClelland, who moved the cabins or took them apart log by log and put them back on new foundations. McClelland’s team put in new systems for solar power, drinking water, and wastewater to allow for more modern comforts while protecting the quality of Flat Creek.

McClelland found old newspapers stuffed between logs for chinking. He opened up one and found a box score for a baseball game in which Babe Ruth hit two home runs. It disintegrated into dust before he could share it too widely. “We always thought the place was haunted—by friendly ghosts,” McClelland says. On one calm day, when the surface of Flat Creek Lake was as still as glass, he looked over at the Cissy Cabin, and the drapes were moving like they were blowing in a breeze. “There was not a breath of wind that day,” he says.

The ranch’s colorful and occasionally checkered history—a lessee built a dam on Flat Creek in 1952 to create the lake without a permit, the rumored horse rustling in the early days, an outfitter pleading guilty to hunting violations in 1981, bouts of drinking and even gambling when the state cracked down on saloons in town—mirrors the history of Jackson Hole, says Kunstel. The remote location “lends itself to freewheeling activity, you might say.” The primitive road, with potholes sometimes deep enough to swallow a Subaru, is “part of the mystique of the place,” she says, making it hard to reach.

In the lodge today, guests still can play the keys of Cissy’s piano, an upright Beckwith Concert Grand she had hauled to the ranch by wagon in 1923. Walking the trails or casting into the lake, listening to the wind rustle the pines over the rushing of the creek, one can picture the Countess of Flat Creek or cowboys Carrington and Cole still roaming their cherished hideout. Kunstel has never seen a ghost, she says, but when a place is this alive with history, there doesn’t have to be a phantasmal apparition for a person to feel like he or she is walking through the past. Flat Creek Ranch welcomes guests from late May through early October; flatcreekranch.com. JH