Read The

Current Issue

Cam Sholly

National parks are part of the family for Yellowstone’s superintendent.

// interview by Dina Mishev

A third-generation National Park Service employee, Cam Sholly assumed duties as the superintendent of Yellowstone National Park in October of 2018. It was also in Yellowstone, in 1990, that he started his NPS career. And it was because his father, Dan Sholly, was Yellowstone’s chief ranger in the 1980s that Sholly graduated from Gardiner High School in the eponymous town just outside the park’s northern entrance. “Yellowstone means a lot to me,” Sholly says. Between doing trail maintenance in the park and returning as superintendent, Sholly worked as a seasonal backcountry ranger in Yosemite (among other ranger “grunt” jobs) and was the chief of ranger operations in Yosemite National Park, superintendent of the Natchez Trace Parkway, and region director, Midwest Region for the National Park Service. As the latter, he oversaw 61 national park units in 13 states. “I have a deep appreciation for the diversity of parks we have in the system,” he says. Outside of his career with the NPS, Sholly is a veteran of the U.S. Army (he deployed with Operation Desert Storm in 1991) and served on the California Highway Patrol. We talked with him about Yellowstone and the NPS.

Q: Tell us about the first and second generations of NPS employees in your family.

CS: My grandfather was the chief ranger of Shenandoah and Big Bend and, in the 1950s, superintendent of Badlands. My father worked for the NPS throughout my childhood.

Q: So, did you move around a lot as a kid?

CS: I was a small boy in Yosemite and spent five years in grade school at Crater Lake. There were three years at Hawaii Volcanoes in middle school. And then I finished out high school in Gardiner, Montana, when my dad was at Yellowstone.

Q: What did you take away from growing up in these places?

CS: What sticks with me the most is the clear diversity of what different national parks have to offer, and also a true appreciation of the value of the resources these parks protect, be it a volcano in Hawaii or the deepest lake in North America

(Crater Lake). This is a very special system we have, and it sets the standard for

the world.

Q: Having now experienced even more national park units thanks to you own career, what do you think is most special about Yellowstone?

CS: For all of the attractions and beautiful aspects of Yellowstone, like Old Faithful and the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, there is no substitute for being in such a wild environment away from developed areas and people. Yellowstone is one of the few places where you can do that. You can experience a piece of primitive America here and go days without seeing people and allow yourself to be absorbed in the wild. That’s a special thing.

Q: As superintendent, do you actually have time to get out and enjoy Yellowstone?

CS: I did over 230 miles in the park’s backcountry last year.

Q: And were you able to be absorbed in the wild?

CS: I think once I was a mile from the road, I counted 25 people over the whole summer. So, yes.

Q: Do you still find yourself impressed by the park’s wildlife?

CS: There is so much great wildlife in Yellowstone, and I find myself regularly awed by grizzly bears, wolves, and bison in particular. These three animals are incredibly symbolic in so many ways. Wolves and bison are really good reminders of where we’ve been not too long ago. One hundred years ago, we wiped out all of the wolves in this park and almost killed every bison. There were less than 25 bison in the 1920s, and today they’re now at a level we haven’t seen in the park since 1872. And the reintroduction of wolves is a great success story. Seeing Yellowstone’s wildlife is always a special thing.

Q: What about the park’s aquatic species?

CS: One of my favorites is cutthroat trout.

Q: Do you fly-fish a lot?

CS: I work too much to take advantage of as much fishing time as I would like, but I do spend as much time as I can on or near the water. And there is water everywhere here. If I’m out backpacking on a weekend, I normally take my fishing rod with me.

Q: Did you fish here during high school?

CS: One of my first jobs ever was flipping burgers at Mammoth at the Grill, that was the summer of 1985. I also worked in the sporting goods section of the General Store in Mammoth that summer. Most of what I recall from that job was talking to visitors about fly-fishing and fishing and selling lures. And also selling film for cameras.

Q: Aside from visitors no longer using film, what is a big change you’ve noticed in Yellowstone between the 1980s and today?

CS: I think other people would say congestion, but what people don’t realize, is that even back then, when Yellowstone was getting about 2 million visitors a year, there were traffic jams. Seventy percent of visitors to Yellowstone are first-time visitors, and most have never seen a grizzly or bison in the wild. When they get here and see that, they don’t really care if they’re stuck in traffic. The narrative about visitors today overrunning the park is true within a very, very small percentage. Yellowstone is 2.2 million acres, and there are 1,750 acres of paved roads, parking lots, and pullouts. So, it’s a big problem, but in a very small portion of the park. The wildness that I think is the heart of Yellowstone is unchanged.

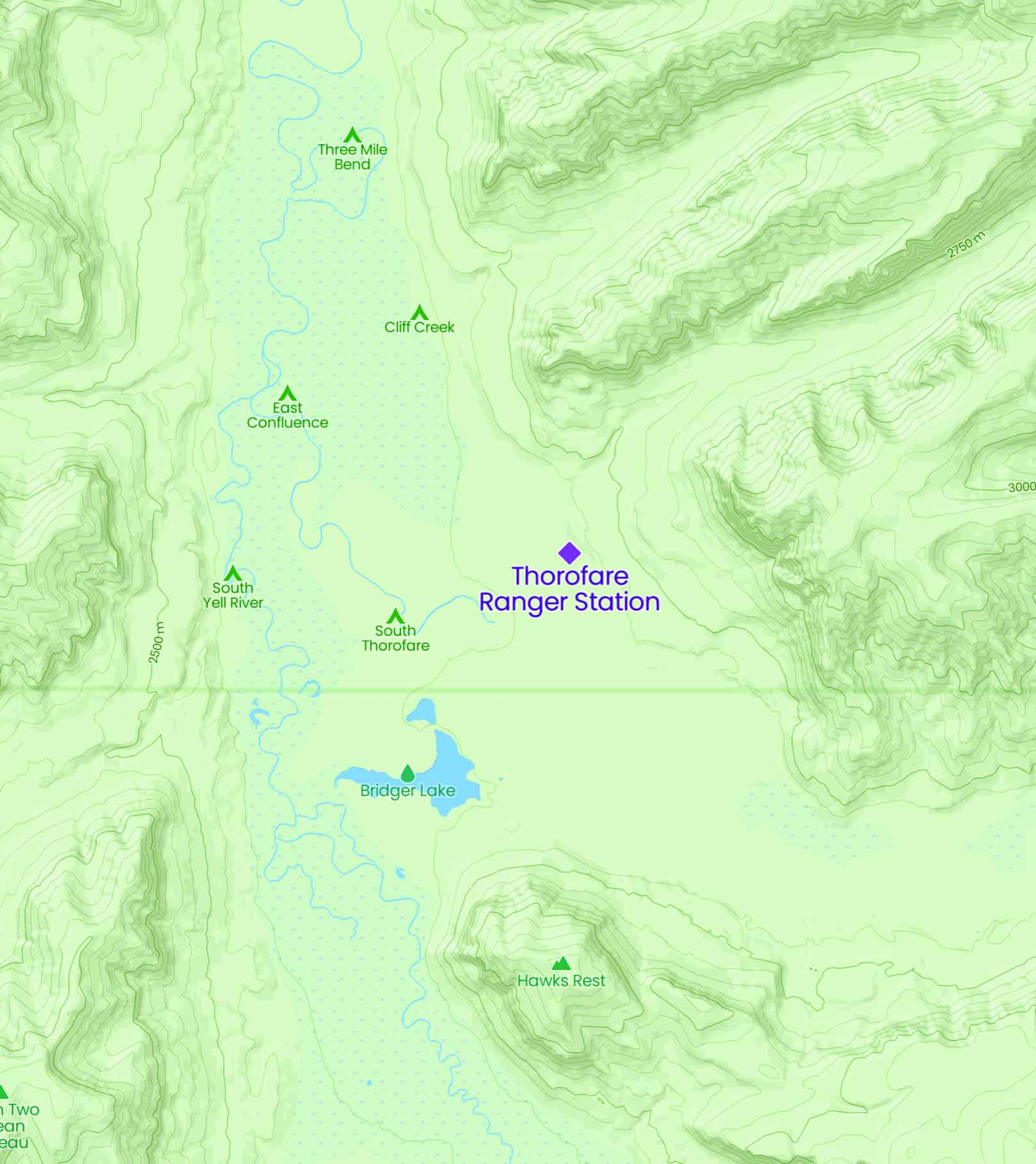

The Thorofare

Sholly’s first park service job was doing trail maintenance in the backcountry of the Thorofare area of Yellowstone. The Thorofare,

in the southeastern corner of the park and adjacent to the Washakie and Teton Wilderness Areas, is the largest roadless area in the continental U.S. and, according to a 2016 article by Wyoming-based writer Mark Jenkins in The Guardian, the only place in the Lower 48 States where you can be 20 miles from the nearest road. The Thorofare is home to grizzly bears, wolves, wolverine, and lynx, although the populations of the latter two species are so low it’s highly unlikely you’ll spot one.

In the summers of 1991 and 1992, the Thorofare was also home to Sholly. “The Thorofare is the most remote place in the Lower 48,” he says. “Living there for two summers, I saw almost no one. I’ve been back five times since becoming superintendent and have still seen hardly anyone there.” The Thorofare Ranger Station is the most remote cabin in all national parks outside Alaska.

JH