Read The

Current Issue

Winters of Wonder

Winters here are always special, but some are truly extreme.

by JIM STANFORD

JACKSON RESIDENT STEVE Ashley had just acquired Valley Bookstore as winter arrived in 1978. He and his then-wife were living in a cabin up Porcupine Creek, about a mile and a half from the nearest plowed road. Upon returning from work late that December, as temperatures plummeted to 20, 30 and even 40 degrees below zero, the two had to don skis to reach the cabin. Then it was time to make a fire in the stove and chop ice from the creek so their horse had water to drink.

“It was probably one of the greatest and yet hardest winters we ever had,” he recalls. “I loved it. But we divorced a year later, and that might have had something to do with it.”

In the record books and lore, the holiday week of 1978-79 was one of the coldest stretches in the history of Jackson Hole. Mercury thermometers froze at 50 below on the night of New Year’s Eve, although some readings were reported as low as 63 below. Residents lit charcoal fires beneath the oil pans or used blowtorches in mostly futile attempts to start their car engines.

“Everybody should have an experience like that and make it through it,” says Ashley, who is now sixty. “Extremes show you what you can do. Some days you just feel like you’re so alive.”

To a newcomer, it seems every winter in Jackson Hole yields some sort of extreme, whether of wind or snow or cold. And in a valley where snowfall is critical for the economy—and communal well-being—weather is a source of endless fascination, and hype. Today’s technology allows us to monitor temperature and winds in real time and watch on a webcam as the snow piles up on Teton Pass.

To help keep weather in perspective—don’t go posting on Facebook about the latest storm being the biggest ever, bro!—here are a few recollections from winters past. Imagine what the Twitter feeds would look like if any of these phenomena occurred today.

THE DEEP FREEZE OF 1978-79

By December 9, 1978, the low temperature at night already had hit 24 below zero. Controversy was flaring over a proposed oil well up Cache Creek, and the Jackson Hole Ski Area had just opened its new Crystal Springs double chair. On December 16, Neil Rafferty cut the ribbon for the new lift bearing his name at Snow King; about one hundred people braved subzero cold to attend the opening.

Then the deep freeze set in. “Frigid temperatures paralyze valley,” read the front page of the Jackson Hole News on January 4. The weather box, normally found inside, had been moved to the cover, displaying lows of -26, -45, -49, -50, and -44, in succession. The high temperature for New Year’s Day was -27.

Adding to the misery, the power went out for six hours, as brittle lines snapped. Plants died inside houses, water froze in the toilet. Gear shifts and windows broke in cars as owners tried desperately to start engines. After a brief thaw, low temperatures again hovered around 30 below for much of the following week.

Still, life went on, and in many cases, merrily. On New Year’s Eve, a crowd stood in line at Jackson Hole Cinema in 40 below to watch a screening of Animal House. The News reported, “They got inside only to have the power go out and be told that they would have to be given a refund.”

Jack Huyler recalls attending a holiday party at the home of the late Fred and Liz McCabe in Moose. A Saint Bernard and cat were outside, seemingly unaffected by the cold. When the cat came in, “Somebody rubbed its head, and the tips of the kitten’s ears fell off,” Huyler says. “It was the skin part that’s not protected by any hair.”

Meteorologist Jim Woodmencey says the official reading of 50 below zero on January 1 was the lowest recorded in modern Jackson Hole history. It’s possible the thermometer at the Forest Service headquarters froze and the temperature was actually much lower, he says, citing other reports as cold as 63 below.

THE DROUGHT OF 1976-77

Throughout autumn of 1976, dry weather persisted. “Sunshine has skiers tense,” read the headline of the November 24 edition of the News, above a photo of ski columnist “Fast Eddie” Wiand posing on roller skis by the bare slopes of Snow King.

By December 15, only twelve inches of snow had fallen at mid-mountain at the Jackson Hole Ski Area. Owner Paul McCollister had turned to cloud seeding, at a cost of $4,000 per week. “They sure can’t do much with blue sky,” he told the News. The Mangy Moose was hosting snow dances.

The Ski Corp. laid off sixty-seven employees before Christmas, retaining a skeleton crew of nine to run the post office, sewer and water system, and property management office. For one week in mid-December, Arne Frumin, a General Motors employee from Michigan, had the entire sixty-room Teton Village hostel to himself. “This has been the quietest and most peaceful vacation I have ever spent in a ski area,” he told the News.

On January 12, columnist Wiand wrote, “The Jackson Hole area is currently experiencing one of the strangest winters that can be remembered by damn near anyone.” Many residents began making plans to head south for the winter. Those who remained had concerts by Doc Watson and Pure Prairie League at the Teton Village Festival Hall to help soothe their pain.

The aerial tram opened in early February, but Apres Vous, Casper, and Teewinot closed because of a lack of skiers. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation said the winter was the driest on record, according to precipitation records dating to 1918. Although barely enough snow fell in late February and early March for resorts to limp to the finish, the News reported, “If we live long enough, the winter of ’77 will certainly be one we’ll be telling our grandchildren about. That was the year it didn’t snow—or rain—or hail—or sleet.”

THE FURY OF 1986

As Valentine’s Day approached in February 1986, a ferocious storm began pummeling the Hole, ideal for lovers to shutter themselves inside. Winds hit one hundred miles per hour. The storm began February 13 and would last for twelve days, dumping eight and a half feet of snow containing an estimated twelve and a half inches of water. Snow King closed February 18, “when rain turned city streets into rivers,” the News reported.

On February 13, a slide in Glory Bowl buried two cars on Highway 22, forcing the drivers to dig themselves out. On February 17, patroller Tom Raymer was killed by an avalanche during hazard-reduction work on Moran Face at Jackson Hole. He was the second patroller to die at the resort that season; Paul Driscoll was killed by a slide in Rendezvous Bowl in early December.

On the morning of February 24, ski patrol gunner Kirby Williams fired a 105mm recoilless rifle with four pounds of explosives into the Headwall, triggering a fracture a quarter-mile long with a crown between six and seven feet. After running down onto Gros Ventre, the slide appeared to lose steam but initiated a “slower-moving river of wet snow,” the News reported. The wet slide plowed everything in its path, destroying the coin-operated Marlboro Ski Challenge race course and Halfway House near the bottom of Thunder chair. “We saw the trees lay over like matchsticks,” Gary Poulson, Bridger-Teton National Forest avalanche fore-caster who was watching from the tram dock at the resort base, told the News.

The avalanche ran one and a half miles, coming to within 200 feet of a home in Teton Village. Ski patroller Renny Jackson, arriving at work, began backing his car out of the resort parking lot upon observing the slide’s approach. Teton Pass was closed by avalanches for more than two weeks. In the Snake River Canyon, Highway 89 was blocked by a debris pile fifty feet deep. The Bureau of Reclamation said precipitation for February was 329 percent of normal, and runoff on the Snake River that spring was the highest recorded—until …

THE BOUNTY OF 1996-97

While the winters of 2008 and 2011 each saw more than 500 inches of snow blanketing Rendezvous Mountain, the winter of 1996-97 remains the biggest ever for mountain snowfall.

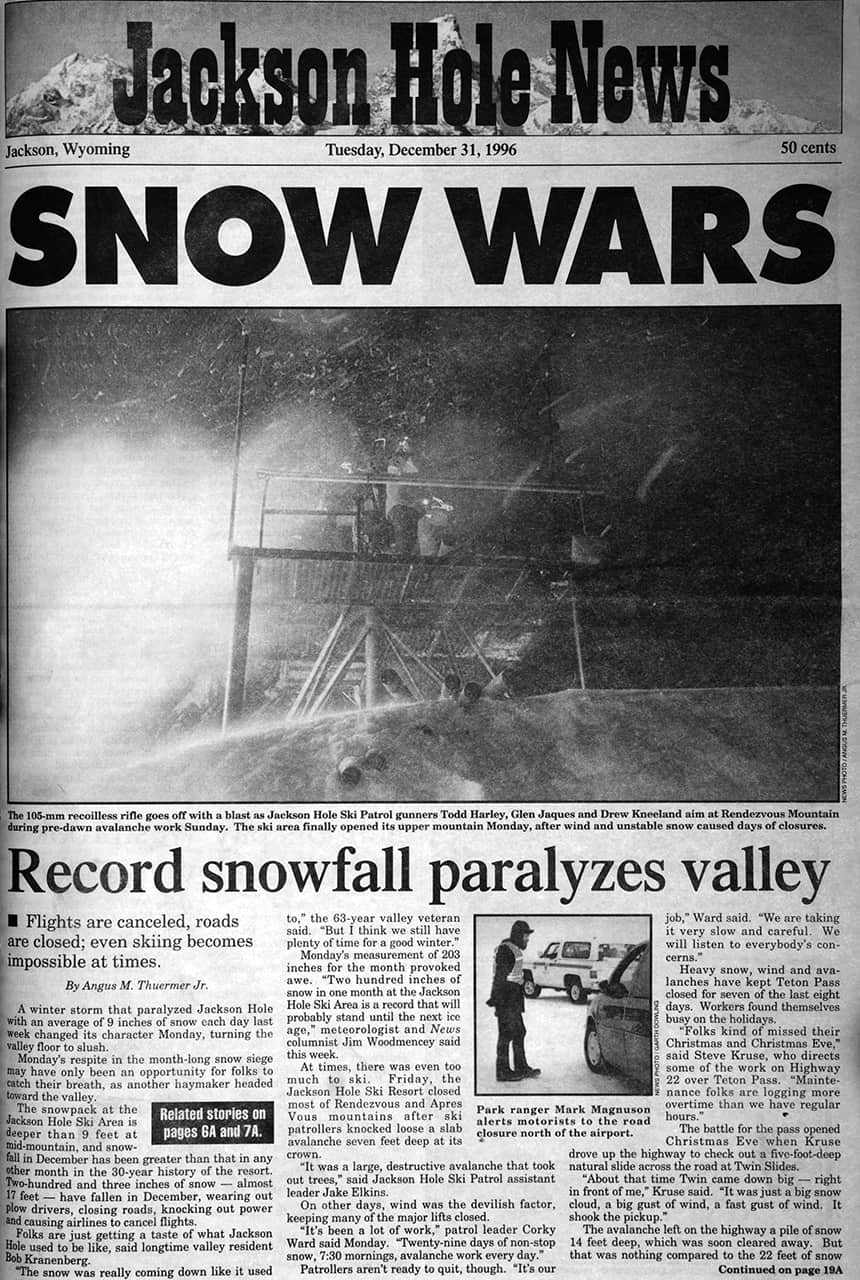

The season began with 225 inches of snow in December 1996—the most ever recorded in one month and more than the entire total for several winters.

Meteorologist Woodmencey wrote in his News weather column, “Two hundred inches of snow in one month at the Jackson Hole Ski Area is a record that will probably stand until the next ice age.” Five hundred and seventy-seven inches fell by the time the lifts closed to the public April 6. Runoff in the Snake River Canyon that June would top 38,000 cubic feet per second, the highest ever recorded.

Old-Timer Tales

While these winters brought some of the most extreme weather ever recorded, longtime residents tell similar stories from earlier Jackson Hole history.

Jack Huyler recalls the cold of 1948 being so severe that barbed wire snapped along a fence on his family’s ranch, killing his father’s favorite horse.

During a deep freeze in 1977, Homer Richards said he could remember only one night colder: February 8, 1933, when the temperature hit 63 below. He traveled by horse-drawn sleigh to a dance at Andy Bircher’s in Wilson. “We kept warm by dancing until nine o’clock the next morning and drinking homemade dandelion wine,” he told the Jackson Hole News.

Edith Vincent, who was ninety-three during the winter of ’77, told the paper about the blizzard of 1949, when Jackson was completely snowed in for three weeks. Helen Gill spoke of 1928, her first winter in Jackson, when all the water pipes in town froze. “Holes were dug all over the streets to get a fire down to the pipes,” she said.

Teton ski pioneer Bill Briggs recalls that during the deep freeze of 1979, it was too cold to run the lifts at Snow King. Briggs, who was head of the ski school, and assistant Jim Sullivan taught skiers in the hotel lobby, and then they all hiked the mountain and skied into Leeks Canyon. “That was just terrific,” Briggs says.

According to a climate study meteorologist Jim Woodmencey prepared for the Town of Jackson in 2008, average temperatures have increased since 1950, with more precipitation and less snow. Warmer temperatures in March and April likely have changed some snow to rain.