Read The

Current Issue

A short, scenic snowshoe or Nordic ski brings you to the Murie Ranch, a historic crucible of the conservation movement.

By Lila Edythe

NOT TO BE too woo-woo or anything, but I always feel the Murie Ranch—where Margaret Thomas “Mardy” Murie, often called the “Grandmother of the Conservation Movement,” lived for more than fifty years—before I see it. The ranch has a peacefulness and tranquility that is palpable. “There is a definite magic about the place,” says Dan McILhenny, who has lived in one of the ranch’s rustic cabins for six summers as a volunteer docent. “My wife and I feel it, and I hear visitors talking about a positive energy. I always feel at peace there.”

But the ranch is more than peaceful. It is a national historic landmark because it was the former home of Mardy; her husband Olaus Murie; his half-brother, Adolph Murie; and Adolph’s wife, Margaret (who happened to be Mardy’s half-sister). All four of these Muries spent their lives working to conserve the wild lands and wildlife of the United States. Much of their work happened at this ranch.

Because of its ties to the Muries and the conservation movement, the Murie Residence was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1990. The designation was expanded in 1998 to include the Murie Ranch. In 2006, the Murie Ranch Historic District was additionally honored with its designation as a National Historic Landmark.

While the one dozen-ish cabins and accessory structures are closed in the winter, this is my favorite time to visit the ranch—when each cabin is an isolated islet rising from a sea of snow and it’s not difficult to imagine you’re the only person in the world. McILhenny says winter was the Muries’ favorite time here, too. Olaus and Mardy, in particular, were drawn to this property, which was built in the 1920s and operated as the STS Dude Ranch until the Muries bought it in 1945 because it reminded them of the wild solitude of Alaska, where both couples had spent significant time. “It’s my understanding they felt that the winter times they had here mirrored what they had had up in Alaska,” McILhenny says about Mardy and Olaus. “I think they were surprised and happy to have found a place in the lower 48 that felt similarly wild.” Mardy once wrote about the ranch, “This piece of river bottom was my favorite spot years before we ever dreamed of owning it.”

Today, Grand Teton National Park’s Craig Thomas Discovery & Visitor Center is only about three-quarters of a mile from the ranch, but the ranch still feels like its own world. Take a break from snowshoeing or Nordic skiing—the only ways to reach the ranch in winter—to sit on the porch of one of the many cabins and enjoy the silence. If you’re lucky, maybe you’ll feel the magic McILhenny and I do. Or maybe you’ll feel the history; these porches and cabins were the site of many of the meetings, debates, and discussions that birthed the modern conservation movement, including the landmark Wilderness Act of 1964. It was here that Olaus wrote wildlife-management and conservation texts that are still used today. He was here when he wrote in an essay, “Wilderness should be treated as a national asset, not as a commodity to be bartered, but as a place where people could regain a natural sense of dignity, harmony, tranquility, and individuality.” The Murie Ranch is not officially a Wilderness Area like the 111 million acres the 1964 act now protects, but it is a national asset and welcomes all to enjoy its harmony and tranquility.

The Wilderness Act was passed in 1964, a year after Olaus Murie’s death. Today this act protects 111 million acres of Wilderness Areas from coast to coast.

Half-brothers Olaus and Adolph Murie married half-sisters Mardy Thomas and Louise Gillette, and the rest is history. Meet the four Muries who together bought what had been the STS Dude Ranch and then used it as a base from which to change the face of conservation in the U.S.

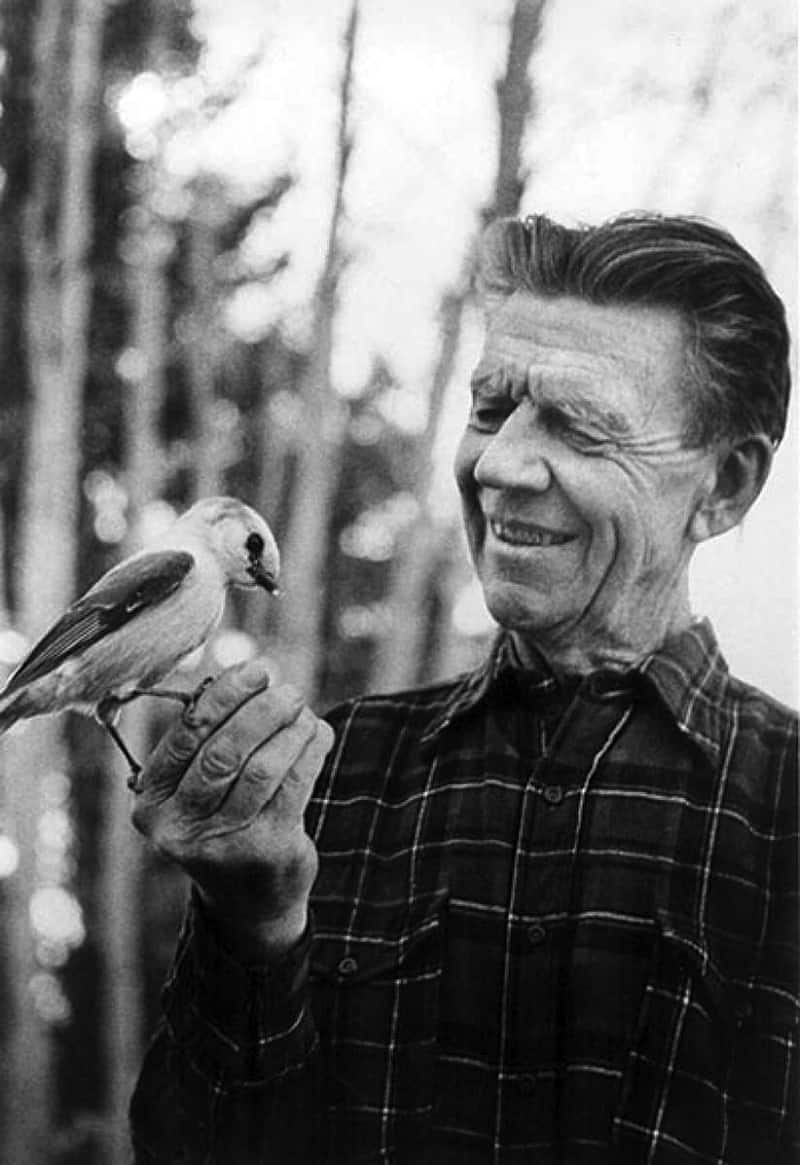

Olaus J. Murie

Born in Minnesota in 1899, Olaus J. Murie studied zoology at Oregon’s Pacific University before working for the U.S. Biological Survey conducting wildlife studies in Alaska and Wyoming. He and Mardy married in 1924, and, in 1927, the two visited Jackson Hole for the first time. Olaus came to study elk herds. In 1945, Olaus was named director of the Wilderness Society. His efforts and work were instrumental in the creation of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and the passage of the 1964 Wilderness Act. He was awarded the Audubon Medal in 1959 for his dedication to scientific excellence and conservation. Olaus died in 1963. He and Mardy had three children: Martin, Joanne, and Don.

“Mardy” Elisabeth Thomas

Margaret “Mardy” Elizabeth Thomas was born in Seattle in 1902, but her family soon moved to Fairbanks, Alaska. In 1924, she became the first woman to graduate from the University of Alaska. That same year, she married Olaus. (Their honeymoon? A six-month, 500-mile boat and dogsled caribou-research trip through northern Alaska.) Together, the two spent nearly forty years working side-by-side in the field and advocating for conservation. Mardy wrote a memoir, Two in the Far North, among other books. Like Olaus, Mardy received the Audubon Medal (awarded to her in 1980). In 1998, President Bill Clinton awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom. She died (home at the Murie Ranch) in 2003.

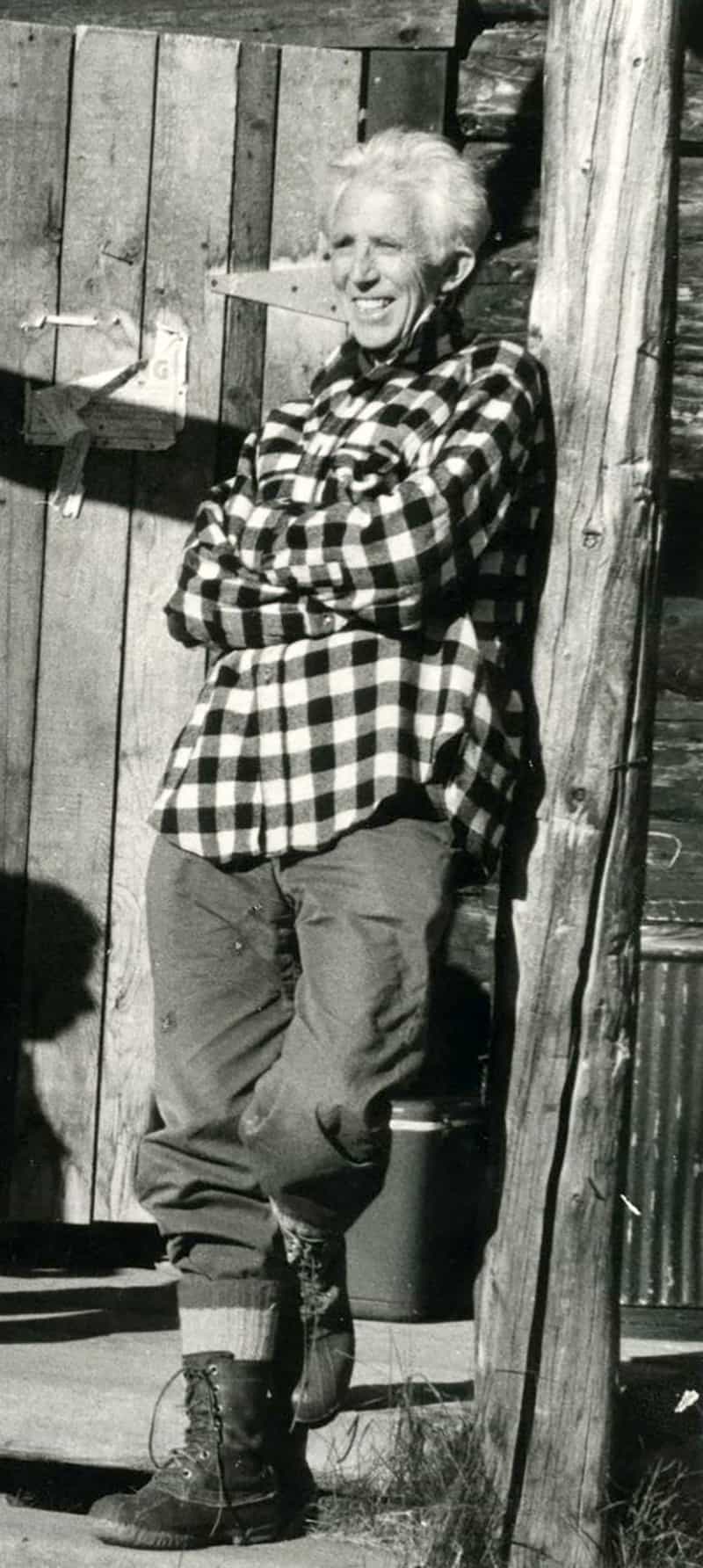

Adolph Murie

Born in Minnesota ten years after Olaus, Adolph Murie shared his elder half-brother’s interest in the natural world. In 1922, he joined Olaus in Alaska to study caribou and went on to spend more than three decades studying wildlife—primarily grizzlies and wolves around Denali National Park and coyotes in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem—for the National Park Service. He and his wife, Weezy, moved to Jackson Hole with their two children, Jan and Gail, in 1945, when the two couples bought the STS Dude Ranch. Adolph studied wildlife until his death in 1973.

Louise “Weezy” Gillette

Louise “Weezy” Gillette was born in Fairbanks in 1912 and met Adolph through her half-sister Mardy. The two wed in 1932 and went on to spend twenty-five summers in a remote cabin in Denali National Park. During this time, Weezy researched and assembled an illustrated manuscript detailing 100 plants and flowers from Denali (she had studied botany). The manuscript was lost for decades but rediscovered in Denali’s archives just before Weezy’s 100th birthday. At that time, there was talk of finally publishing it, but that has not yet happened. Weezy died in Jackson Hole in 2012. JH

Nuts & Bolts

You can drive to the ranch in the summer, but in winter the road and driveway are closed (and not plowed). The Craig Thomas Discovery & Visitor Center is the best place from which to snowshoe or Nordic ski to the ranch; a flat trail between the two is about three-quarters of a mile and deposits you just west of Olaus’s studio. While the Park Service does not groom this trail, the ranch gets just enough visitors that the path, set by other explorers on snowshoes or cross-country skis, is almost always obvious. (If a significant amount of fresh snow has recently fallen in the valley, maybe give it a day for someone to set the path.) If you’re at all worried about getting lost in the woods, you can snowshoe or Nordic ski up the ranch’s driveway, which is off Moose-Wilson Road across the road from the post office in Moose. This route is about the same distance and also flat but doesn’t have the drama of cabins materializing in the middle of cottonwoods and conifers. Free, tetonscience.org/locations/murie-ranch/