Read The

Current Issue

R Park

A new public park on the Snake River is on private land.

By Frederick Reimers

ON A TOUR of the then-unfinished Rendezvous Park (R Park) last August, yellow front-end loaders whiz around an open space between tall cottonwood trees, spreading topsoil on what will be a central meadow. A trio of young boys clambers eagerly up a twenty-five-foot-high earth mound, sending small cascades of dirt down.

“By next summer, these berms will all be grassy,” says Elisabeth Rohrbach, the park’s managing director. “I don’t think they mind the dirt at all,” says the mother of one of the boys. That, says Rohrbach, is exactly the point of this place.

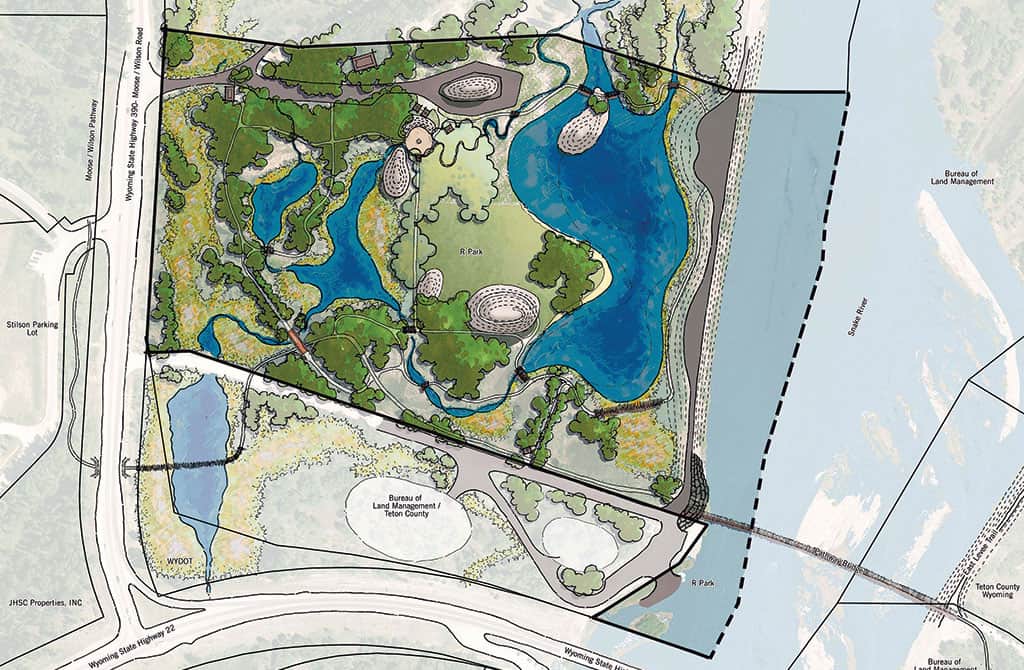

The site was a working gravel pit for twenty years, so extensive rehabilitation is underway, but in the end, R Park’s directors want it to function just as well for wildlife as it does for kids. More unique is the park’s identity—a privately owned parcel with free access to the public. The forty-acre plot on the west bank of the Snake River—near the junction of Highway 22 and Highway 390—was purchased in 2011 by local conservation groups from a developer who had plans to turn it into three large homes. Instead, the park provides year-round recreation for thousands of people in a placid, natural setting.

What it doesn’t include are artificial play structures, says Rohrbach to a small audience of kids and parents. “Studies are showing that children not only need more time outdoors and in nature, but also need that time to be less structured and less scheduled,” she says. R Park’s five knolls are central to that idea—relatively natural spots kids can climb up and roll down or, come winter, sled. Also important are the park’s three ponds, which function as swimming holes in a valley particularly short of them (the Snake River is too cold and swift for swimming most of the year). When the park’s directors sought community input, of the more than five hundred comments, requests for safe outdoor swimming spots were numerous.

WILDLIFE CONCERNS WERE high on that list as well. “Birders were very vocal about keeping habitat as intact as possible,” Rohrbach says. The park works with wildlife agencies and nonprofits to ensure there is optimal habitat for wildlife, including swans, geese, osprey, porcupine, and moose. The cottonwood groves are preserved and extended, the central meadow will be planted with native grasses, and willows and cattails line the edges of the ponds, which are connected to the river and should provide optimal breeding for trout.

Also central to R Park’s identity is its location. Not only does the park feature one thousand feet of Snake River frontage, but it also abuts the busy Wilson Bridge boat ramp. In addition, it is transversed by the newest segment of the valleywide paved pathway system and is the landing point for the brand-new $3.2 million pedestrian bridge over the Snake. “R Park really is at the hub of so much of Jackson Hole’s recreation,” says Laurie Andrews, director of the Jackson Hole Land Trust, whose organization, along with the LOR Foundation, purchased the land. The nonprofit partners created a separate entity, the Rendezvous Lands Conservancy, to administrate the park. It’s an unusual arrangement for a public park, but an essential innovation in a community where land is so expensive. (Andrews won’t disclose the amount paid for the parcel, but says it was “millions of dollars,” and the organization is fundraising $5 million for the park’s rehabilitation and maintenance alone.)

Without the nonprofits’ efforts, R Park could never have been created, says former Teton County Commissioner Ben Ellis, who proposed acquiring the gravel-mining site for a park with county funds during his time as a commissioner. “We just didn’t have the resources,” he says. “The Jackson Hole Land Trust has to be commended for their efforts. This is an amazing gift to our community.”

Note: Fundraising efforts for the Rendezvous Lands Conservancy are ongoing. To donate, visit rendezvouslandsconservancy.org.