Read The

Current Issue

Raising a Lake

Jackson Lake Dam, part of one of the oldest federal irrigation projects in the country, helped make Idaho the potato capital of the world.

By Whitney Royster

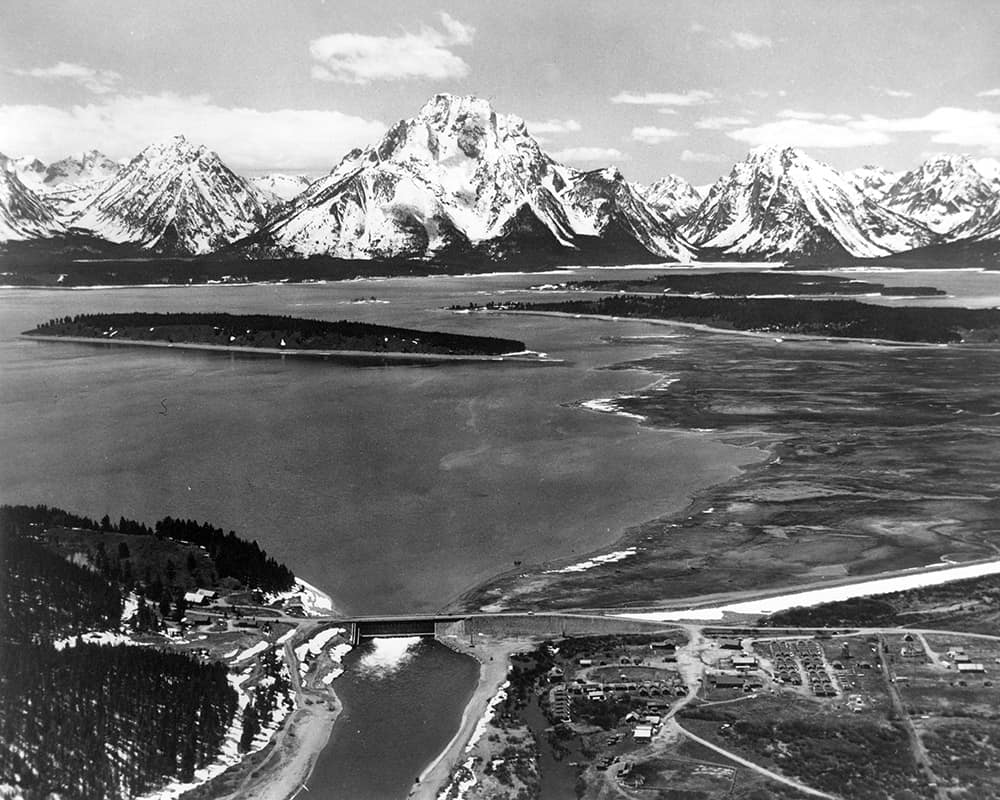

WHEN CONSTRUCTION ON the current Jackson Lake Dam was finished in 1916, historic trapper campsites and homesteads, Native American sites, and at least one sulfur hot spring were submerged. Jackson Lake is a natural lake, but the dam at its outlet raised its surface level by about thirty feet and extended it about six miles north. But it wasn’t all bad news. Jackson Lake Dam, one of five dams built between 1904 and the early 1930s on the Snake River as part of the Minidoka Project, was responsible for the northern part of Jackson Hole getting its first telephone line and nurse. In addition, today’s Grassy Lake Road was built around 1911 to transport 300,000 tons of construction supplies and equipment to the dam site from the railroad terminal in Ashton, Idaho (at that time, it was called Reclamation Road). And the dam helped turn more than 1 million acres of dry land into farmland.

Even before there was a dam, though, there was water—lots of it. Water rushed down from Colter Canyon, from Moran Canyon, and from the Skillet Glacier. The snowmelt came from Waterfalls and Leigh Canyons, and from the Snake River. All of it collected in Jackson Lake, which, although smaller in surface area than it is today, was still more than 600 feet deep. At the southeast end of the lake, water flowed out and went back to being the Snake River. The Snake snaked through Jackson Hole (sometimes flooding Wilson) and Swan Valley, Idaho, and into Oregon and Washington for about 800 miles before meeting the Columbia River and ultimately pouring into the Pacific Ocean.

AS EARLY AS 1889, the U.S. Geological Survey was studying possibilities for increasing irrigation in southern Idaho. Homesteaders in the area couldn’t do anything with their land because there was no water. The Snake River was an easy target, but nothing could be done about it until the Bureau of Reclamation was created in 1902 with the goal of increasing the amount of arable land in the West. Two years later, the agency launched the Minidoka Project with the specific purpose of using a series of dams and canals to control the flow of the Snake River in Wyoming and Idaho, and distribute water to farmers in Idaho. It is one of the oldest Bureau of Reclamation projects. Jackson Lake Dam was the second of Minidoka’s five dams to be built. (The Minidoka Dam in south-central Idaho was the first; construction started in 1904 and finished in 1906.)

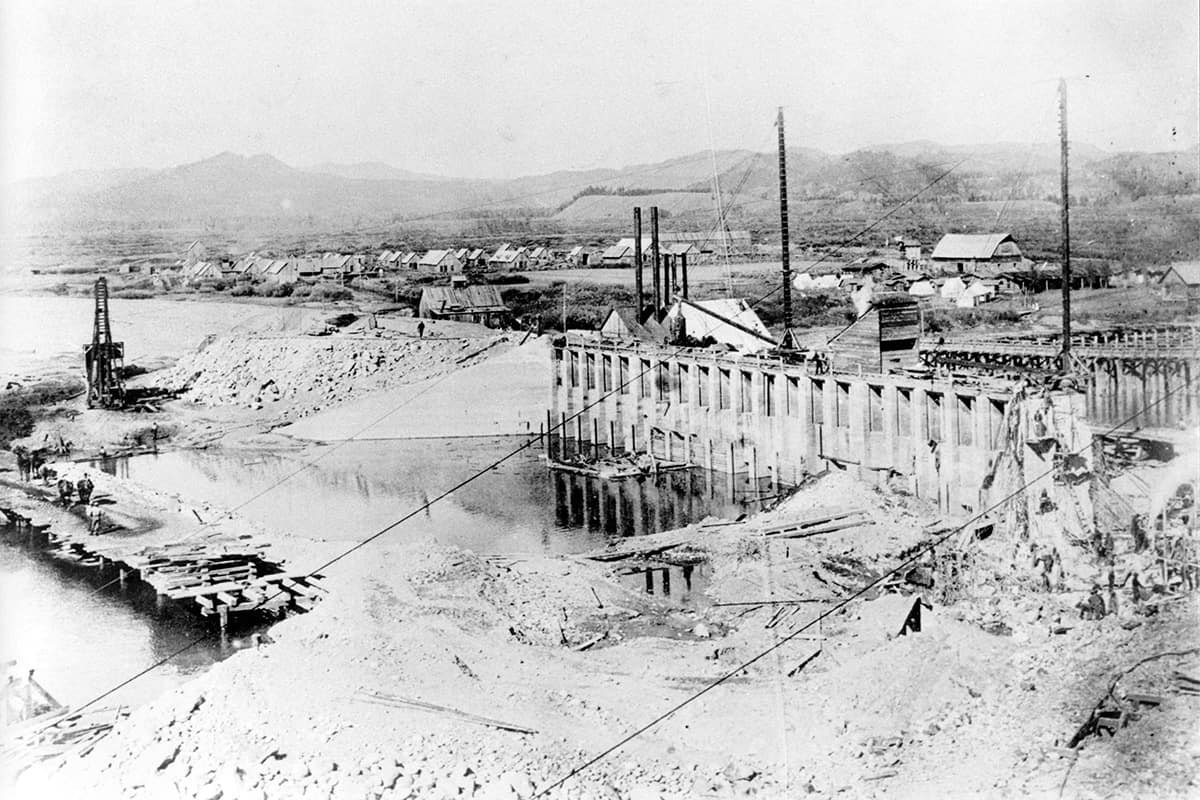

Construction on Jackson Lake Dam began in 1906 and finished within a year. Built with rocks quarried from Signal Mountain and trees felled from nearby canyons, it raised the lake level by about ten feet. That dam failed in 1910, though. About 194,000 acre-feet—a reported ten-foot wall of water at the front—burst out and severely damaged several bridges downriver.

A new, sturdier dam was needed. The Bureau of Reclamation brought in Frank T. Crowe, a recent transplant to the West from New England, where he had graduated from the University of Maine with an engineering degree, to supervise construction. (Crowe went on to be the most famous dam builder in the country—as famous as a dam builder can be. After Jackson Lake Dam, he built the Arrowrock Dam in Idaho, Washington state’s Tieton Dam, and another one you may have heard of called the Hoover Dam. Because Crowe invented a new dam-building system and techniques, he finished the Hoover Dam two years ahead of schedule.) Construction on the second Jackson Lake Dam—it was made of concrete this go-round—started in 1911.

At the time, the population of Jackson Hole was about 300 people, almost all of whom were clustered in the southern end of the valley. The dam was at the northern end of the valley. About 400 workers who were brought in to help with construction lived in a camp built by the Reclamation Service, more than doubling the valley’s population. Because the camp included a hospital, this part of the valley got its first nurse. Of course you can’t just go and set up camps in national parks, but, at the time, Grand Teton National Park didn’t yet exist. (The area of Grand Teton National Park that includes Jackson Lake and Jackson Lake Dam weren’t part of the park until 1950.) Today, three buildings from the camp are still around and in use; the current dam tender, John Bennett, lives in one and works in the others.

When it was finished in 1916—it was built in stages—the level of Jackson Lake was about thirty feet higher and the lake extended more than six miles north of its natural shoreline. While an unknown number of archaeological sites here were lost, this area didn’t fare as badly as the town of American Falls, Idaho, the site of another Minidoka dam. The American Falls Dam created American Falls Reservoir, which required the relocation of most of the town of American Falls.

The current Jackson Lake Dam is the one Crowe and his crew built more than a century ago, although it has been reinforced a couple of times (most recently between 1986 and 1989) to keep up with new requirements for earthquakes.

ASIDE FROM ITS history, Jackson Lake Dam is unique because you can see all the mechanics—there is no machinery or mechanical room hiding anywhere. If you’ve ever been to that other Crowe construction, the Hoover Dam, or to the Buffalo Bill Dam on the east side of Yellowstone National Park, you might have noticed that their mechanics are hidden. Walk across Jackson Lake Dam, though, and you see just about all there is to see: fifteen metal gates, each individually raised and lowered by a gate stem. It is Bennett—whose official Bureau of Reclamation title is maintenance mechanic but is more conventionally known as the “dam tender”—who raises and lowers these gates to release water as the agency’s water operations managers dictate.

Bennett, who has been the dam tender since 2013, uses a tape measure to translate numbers into flowing water. The gate stems are like giant screws that come up to the dam’s deck. They’re covered with simple plastic caps. Take a cap off and an electric motor spins the stem up. (This used to be done with a gasoline engine, and, before that, by hand crank.) Bennett knows that one inch in stem height equals a release of twenty cubic feet of water per second. (Hence his tape measure.) One cubic foot of water is about 7.5 gallons.

While the dam was originally built to irrigate the arid land downriver, today its releases also consider newer user groups, including commercial rafting companies and anglers. Until he retired in January 2017, Mike Beus was responsible for determining Jackson Lake Dam’s releases. Beus, whose office was in Burley, Idaho, started this job in 1996.

The water in Jackson Lake, due to laws in the Wyoming Constitution and compacts created in the 1950s, does belong to Idaho farmers. They pay the U.S. Treasury an estimated amount each year—a number that includes reconstruction costs, operations, and maintenance, minus any credit from water not used the year before. Because Jackson Lake is the highest reservoir in the Minidoka Project, water is taken from lower reservoirs first.

While this gives water managers the flexibility to consider other local river users, it also makes their jobs more difficult since the water levels sought by each of the user groups are contradictory: Fishermen like consistent water levels, scenic rafters prefer medium water levels, and whitewater boaters favor higher levels.

Beus remembers a spring meeting in Jackson in the early 1990s (before he was the official water manager) when it was obvious summer lake levels would be low. “Toward the end of the meeting a participant stood up and said, ‘Well, we might as well all go home, because we are never going to reach a consensus,’ ” Beus says. “That’s kind of how we are.” So difficult is the task of managing everyone’s water needs at Jackson Lake Dam that water managers could just as well spin a wheel to determine how much water to release.

What’s not difficult to determine is the success of the Minidoka Project in making otherwise parched land fertile. The project’s five main reservoirs collect water and then distribute it via 1,600 miles of canals and 4,000 miles of ditches. It irrigates more than 1 million acres, including much of Idaho’s potato crop.

The Jackson Lake Dam is on the Inner Park Loop Road in Grand Teton National Park, about one mile before Jackson Lake Junction.