Read The

Current Issue

Sign of the Times

The views from the valley’s roads weren’t always as picturesque as they are now.

By Mark Huffman

FOUR MILES NORTH of Jackson, a white Chevrolet van pulled to the side of U.S. Highway 89. Several people jumped out and ran up East Gros Ventre Butte, across from the National Fish Hatchery. The van, with “Osprey Float Trips” painted on its side, pulled back onto the highway and continued north.

A full moon hung in the clear, dark sky. All was quiet. For about a minute. Then came the sound of metal cutting wood. It wasn’t the whine and growl of a chain saw, but the slow, steady, soothing shoosh-shoosh of a two-man timber saw. Finally, wood splintered, and something thumped into the sage and dirt. The alternating sounds—shoosh and then thump—continued for half an hour. After the eighth thump, the crew went back down to near the road. They hid in the sage until the van came back.

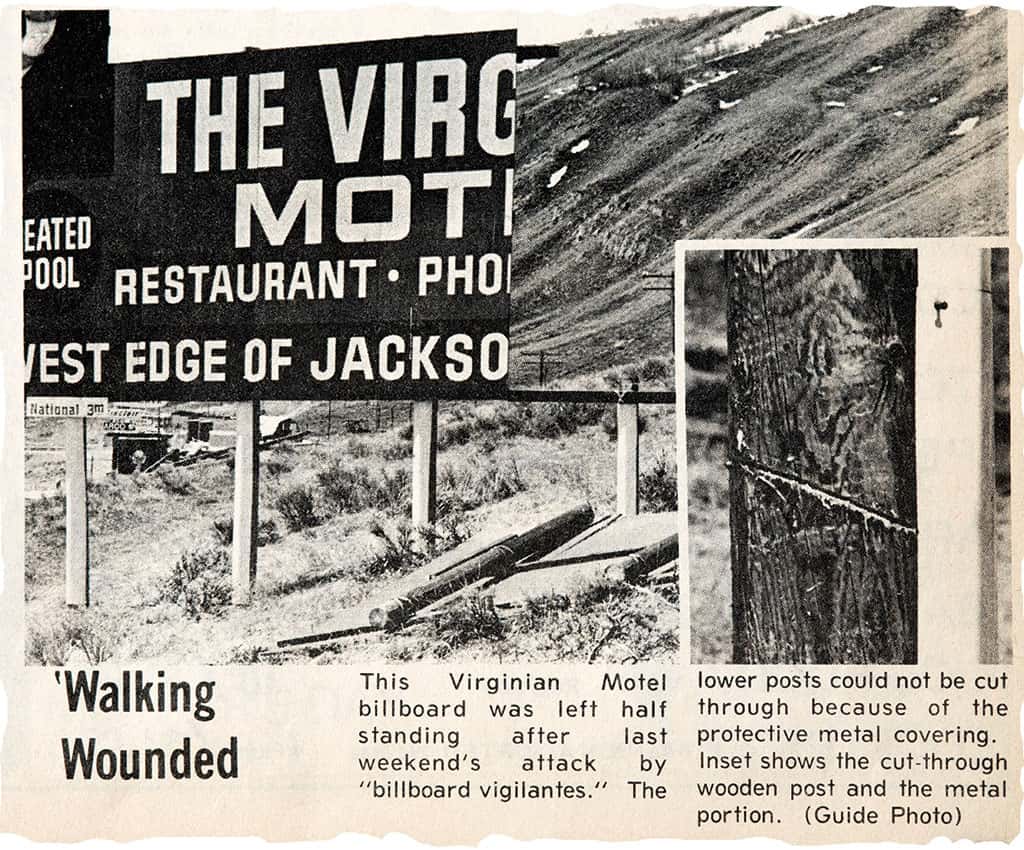

Days later, the Jackson Hole Guide ran headlines about “billboard vigilantes.” Eight signs advertising Jackson businesses had been felled, and no one knew who did the monkeywrenching. The perpetrators of this May 1971 billboard cut-down were never discovered—law enforcement never found them and no one ever came forward to take credit.

Until now.

“I drove the car,” says Gene Downer, the owner of the now-defunct Osprey Float Trips. “I did it as a community service, because the billboards were ugly and they needed to come down. I never told anybody about it. It’s been a secret for about forty-five years.”

BY 1971 JACKSON Hole was on its way to becoming a vacation mecca. Before the Internet, valley hotels, shops, and restaurants tried to capture customers the way they had for decades: via roadside billboards that told passersby what the businesses did and where to find them. That kind of advertising started soon after the Civil War, and exploded in the first decade of the twentieth century when many Americans bought a car. From the 1950s on, roads around this valley were lined with hundreds of signs of every size, some big and professional, others small and handmade. They often stood close enough to each other that they were hard to read. The stretch along the highway north of town, across from the National Elk Refuge, was known as Billboard Alley.

A federal estimate put the national highway billboard count at the time at 80,000. The Wyoming Department of Transportation estimated the state’s billboard population at 6,000. Jackson businessman Bill Bailey, who operated Frontierland, a western-themed town for tourists located smack in the middle of Billboard Alley and where Downer and crew struck, recalled in the Jackson Hole Guide that when he bought this land in 1961, its frontage was lined with forty-nine signs of “all sizes and shapes.” Frontierland was Bailey’s main business, yet he profited from renting sign space.

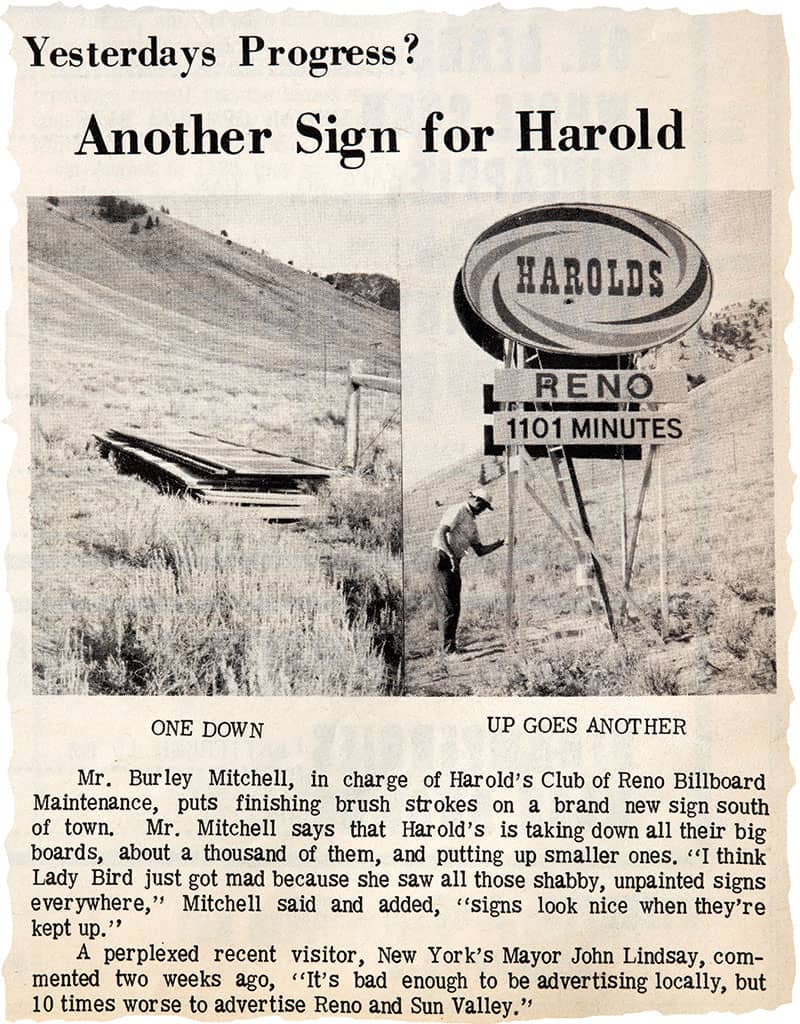

But attitudes were changing. Lady Bird Johnson, wife of President Lyndon B. Johnson, was famous—and ridiculed—for her highway beautification program. She insisted the nation’s roadsides didn’t have to be ugly. In 1965 Congress passed the Highway Beauti-fication Act. The most important part of the act banned signs outside cities that were within 660 feet of a highway that received federal aid, except for those signs advertising businesses on the land where the sign stood.

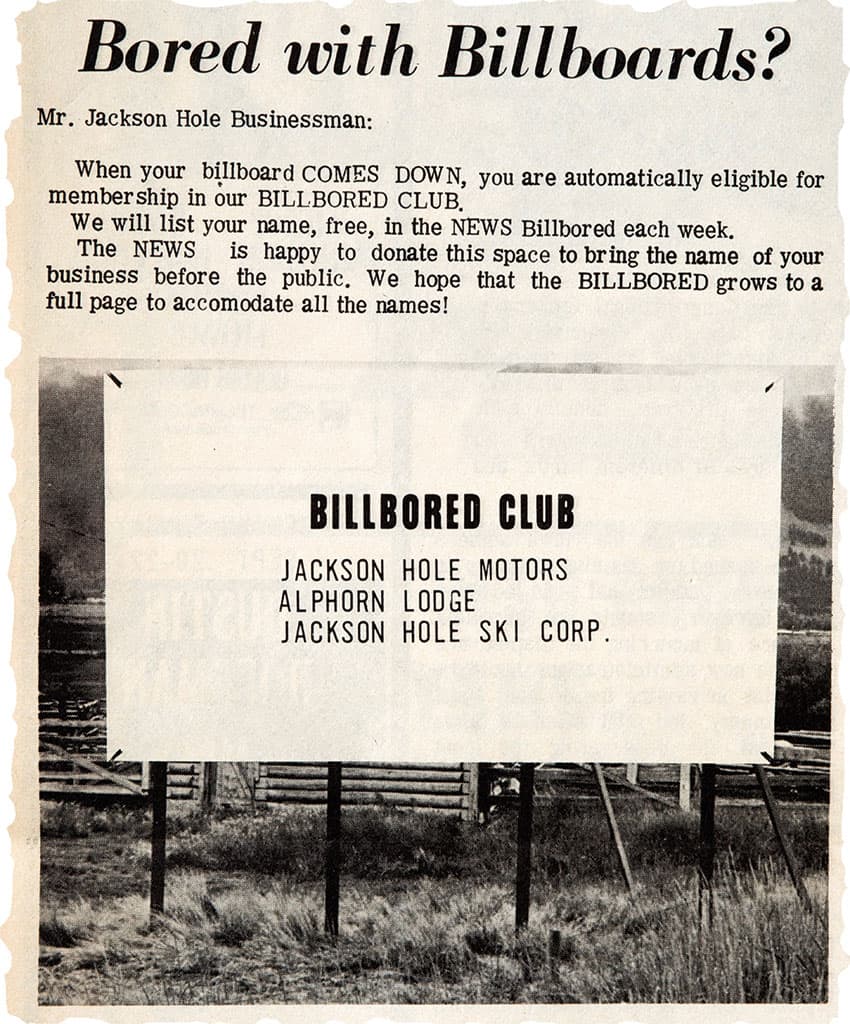

Because of the typical pace of bureaucracy, however, the act wasn’t immediately enforced. In Jackson in 1970 the Guide and the Jackson Hole News campaigned to rid local highways of billboards. A September 1970 survey in the Guide garnered 202 responses. Of those, 194 were anti-sign. In Wilson 267 people signed a petition at Hungry Jack’s general store to banish the signs.

Jackson historian Lorraine Bonney wrote to the Guide that “I find myself getting madder each trip at what I see along the route” into Jackson. “I will never get used to Billboard and Tatter Flag Alley.” Dave Beck, owner of Jackson Hole Motors, took down his own sign at Jackson’s “Y” intersection—where Broadway Avenue and Highway 22 meet—for which he had a sixteen-dollar-a-month contract. He wrote the sign company about it. “Let them sue me,” he told the Guide. “I think the local people would support me.” Jackson Hole Ski Corporation also removed its sign at the “Y” and promised that twenty-one others it had around the region would follow.

The Guide summed up the local attitude, calling the cut-down “an act of vandalism we cannot tolerate.” But the paper’s publisher, Fred McCabe, added, “At the same time the actions of the billboard vigilantes reflect the feelings of probably the majority of the people in the valley—we agree that the billboards look a lot better out of sight in the sagebrush, with only their chain sawed posts remaining.” He urged methods that were more peaceful, and legal. “If it becomes apparent that they are becoming expensive, not money-makers, they will come down,” he wrote.

JANA CRAIGHEAD, NOW Jana Smith and living in southern Utah, was one of the sign cutters who jumped out of Downer’s van. She was a seventeen-year-old high school student at the time. The daughter of environmentalist and grizzly bear researcher Frank Craighead, Smith says it’s too long ago to recall exactly how she joined Downer, Ted Major Jr., “a girl named Kristina,” and others that night. “I just remember wanting to do it,” she says. “The billboards took away so much from the natural beauty of the area; they didn’t belong there. People come to Jackson Hole for the beauty, and the signs drove me crazy.”

The cutters used an old timber saw, one person at each end, and worked their way along nearly a mile of highway frontage. “It was probably eleven or twelve at night, and there was not a lot of traffic,” Smith says. “When there was a car and headlights, we’d duck behind the sagebrush until the car was gone.”

Smith says she thought she was doing something noble. “It was a perfectly clear night, the stars were out,” she says. “It gave me all the more reason to do it. I remember looking over the Elk Refuge and thinking, ‘This place is so gorgeous.’ ” Smith wasn’t scared during the adventure, but says the outcry right after was alarming. Sheriff Boyd Hall told the Guide: “This is vandalism. It’s illegal and we’ll investigate it and prosecute it if we get a case. Personal feelings don’t enter into it.”

There were rumors that the FBI was called in. Neither Downer nor Craighead was ever questioned, but they heard of people who had been. Smith says, “I don’t know how smart it was, but I’m glad I did it. The signs didn’t belong there.”

Her father, who was a major force behind the idea and writing of the Wilderness Act, suspected something and asked her. “He knew I was involved,” she says. “I told him I was there, and he shook his head and said, ‘You shouldn’t have done that.’ But he smiled, like he was telling me, ‘Good work.’ ”

CRAIGHEAD WAS DONE after one shot, but some of her classmates at Jackson-Wilson High School went sign cutting repeatedly, creating a “Bill-board Committee.” “Craig Shanholtzer and I put it together,” says Tom Grant, seventeen at the time and now a building contractor in Nevada. “We were the first eco-terrorists, and pretty soon there was a half-dozen of us on the billboard committee. But mostly it was Craig and I.”

Grant had the same motivations as Downer and Smith, and was cutting down signs with friends before May and into the summer. “Back in those days, when you approached town from the north or south, for miles it was a long stretch of billboards,” he says. “It was a disgusting mess.” He and Shanholtzer, who went on to join the U.S. Ski Team as a downhiller, wore dark clothes and used a bow saw when they went out. “One would drive and one would cut,” Grant says. They worked mostly south of town.

“The first night, we didn’t cut them all the way through,” Grant says. “We cut them within an inch and left them standing, knowing the first time the wind came up it would knock them all over.” They chose signs at random. “What was on the sign had nothing to do with it, it was just the fact that it was there,” Grant says. Some sign owners didn’t give up easily. “There were certain signs we cut down three or four times.” One night when they wanted to go big—both of them cutting—Grant and Shanholtzer enlisted the help of Downer. “They came knocking at my door, and said, ‘We want to cut down some billboards.’ I didn’t know them that well, but through the underground they heard that I was part of it. They were ready to go without any hesitation whatsoever.” Downer didn’t hesitate, either.

AS IT TURNED out, it wasn’t any of the vigilantes that rid Jackson Hole of its billboards. It wasn’t anyone in Teton County. The federal government slowly began enforcing the beautification act, squeezing states to ban billboards. If states didn’t comply, they could lose their federal highway funding. In August 1965 the Guide reported that the Wyoming Department of Transportation had already removed more than 2,500 billboards and that another 3,400 were targeted. The state was removing as many as two hundred a month.

Smith knows the sign cutting didn’t win the war, but she thinks it was part of a change in consciousness about how people lived in the world and treated the environment. “We didn’t take them all down, but we felt like we accomplished something—people realized it was nicer without the signs,” she says.

“It was a good thing,” Grant says. “The message got out, I think.”

Downer, now seventy-five and living in New Mexico, says the sign cutting done by a few was the outward expression of what most people felt. More than forty years later he’s proud of what he did, and glad now to admit his part. “I was going to have something printed and announced at my funeral,” he says. “Now I don’t have to do that.”