Read The

Current Issue

Take a Hike Through History

Cache Creek, a wildland area about one mile from the Town Square, is locals’ favorite place to bike and hike. It’s also a large part of how Jackson came to be.

By John Spina

EVEN WITH THE majestic Tetons looming to the west, it was a diverse, narrow canyon on Jackson Hole’s southeastern edge that called to the valley’s earliest settlers. This canyon had gently rising (compared to the Tetons, at least), 2,000-foot-high side slopes and a creek running down its middle. Wildlife was as abundant as wildflowers, and, because the canyon was close to the growing town of Jackson, locals came here for logs and timber to build their cabins.

For all this canyon had to offer, it was its creek that defined it, a fact revealed in its name. The area is not called Cache Canyon, as most similar areas would be referred to, but Cache Creek. Early residents developed a relationship with Cache Creek, and the area is still a large part of Jackson life. Today’s Jacksonites often call Cache Creek the “town’s backyard” because of its proximity to downtown and the many miles of mountain biking and hiking trails that wind through the canyon. As important and popular as Cache Creek is to locals now though, in the late 1800s and early 1900s it was the lifeblood of the valley.

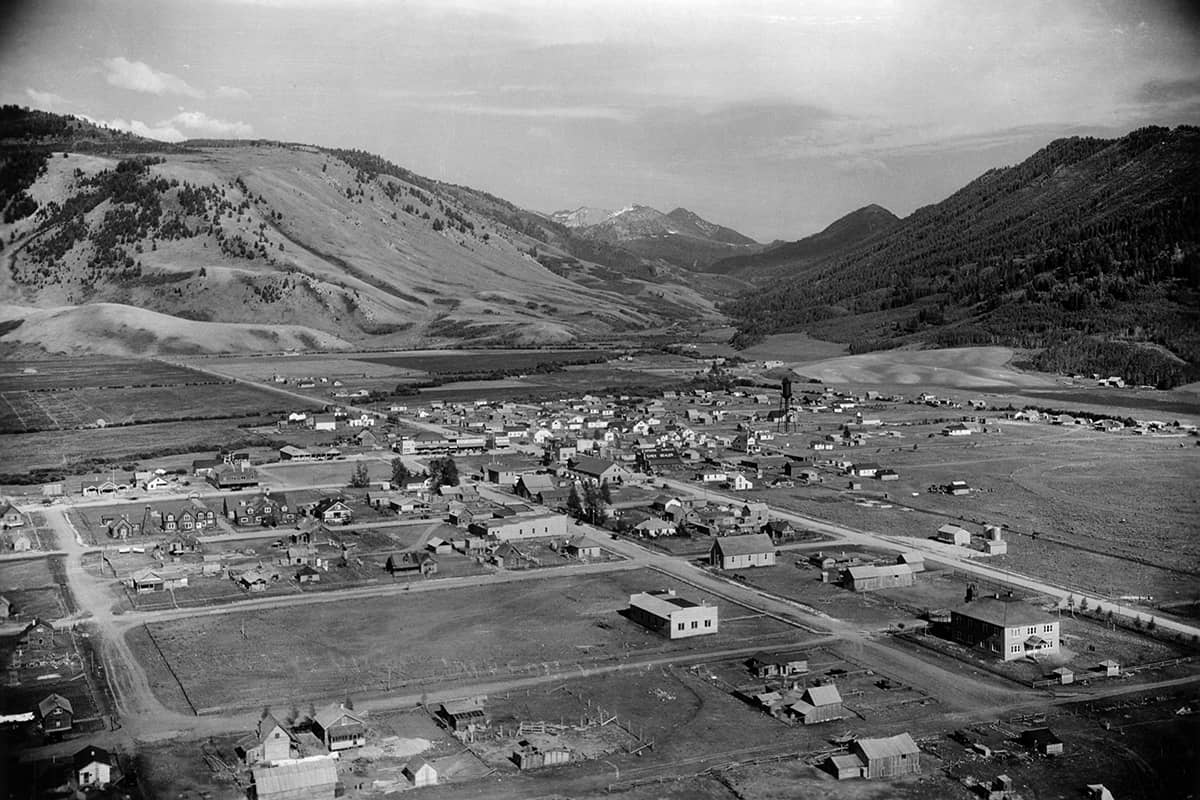

Surrounded by high mountain passes and vulnerable to extreme weather events, Jackson Hole remained largely undeveloped during America’s industrial revolution. Until the 1810s and ’20s, its only human visitors were Native Americans, who passed through seasonally on the trail of game. The first white men to arrive were hunters and trappers like Jim Bridger, John Colter, and the valley’s namesake, Davey Jackson. In the 1870s there were some unfruitful attempts at gold and silver mining in the valley. It wasn’t until 1884 that John Carnes and John Holland became the first Anglo-Americans to take up full-time residence in the valley. They homesteaded at the mouth of Cache Creek. By 1900, the valley’s population was 639. By 1920, it was 1,381. There were many things that drew homesteaders to Jackson Hole, and Cache Creek and its resources helped them stay.

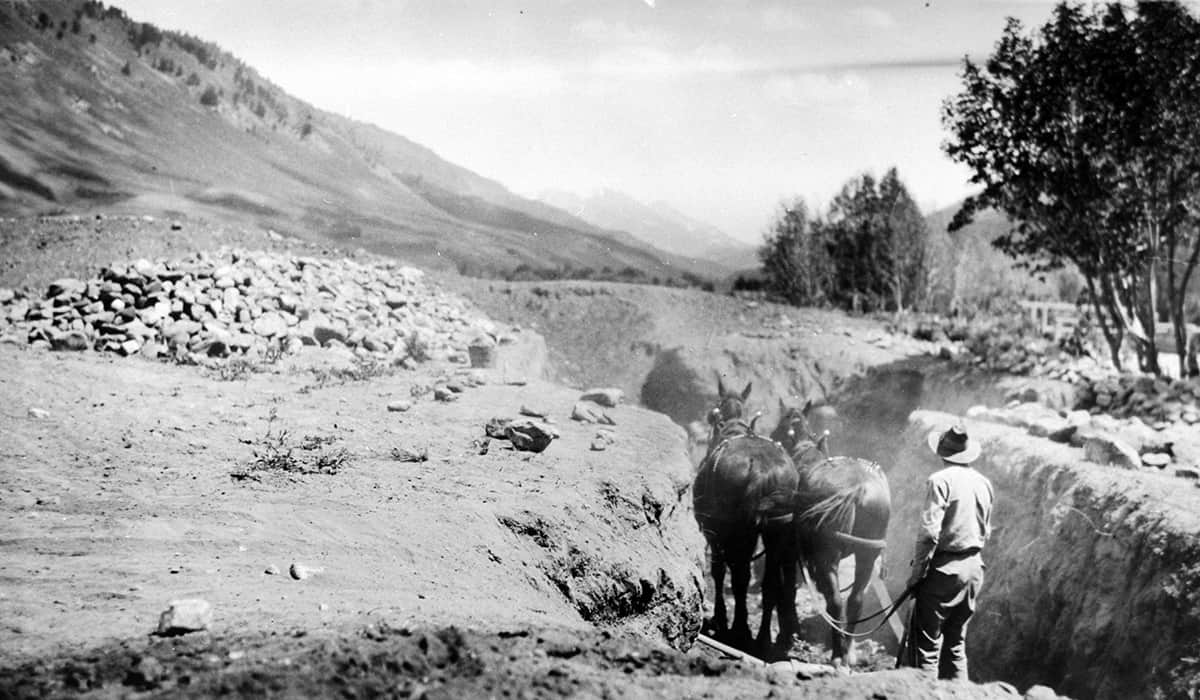

CACHE CREEK OFFERED homesteaders timber for their homes, fresh water, and quick access to wildlife migration corridors for hunting. Eventually, it even provided electricity. In 1918 EC Benson connected two turbines to Cache Creek that could power sixteen nearby homes for three hours each night. His concept proven, Benson convinced the Town Council to let him bring hydroelectric power to the whole town. This was a large and complex project, but Benson was driven. By the last week of January 1921, Benson’s power plant on Flat Creek, a larger creek that flows through the National Elk Refuge before Cache Creek joins it on the northeast side of town, was ready for operation. This power station provided enough electricity for the entire town.

Cache Creek provided another, very different type of power, too: In 1924 John P. Noker opened the Jackson Coal Mine more than four miles up Cache Creek. Because Cache Creek had long been used for timber, was already a popular area for walks, and was a favorite hunting spot of many, trails had been naturally worn in. The “trailhead” back then was one-and-a-half miles west of the current trailhead, near a damn used to supply water to the town. While these unofficial trails served their purpose, they weren’t solid or straight enough to handle the loads coming out of the Jackson Coal Mine. It was so Noker could get his coal to town that the road alongside Cache Creek today was first built. (Before the Jackson Coal Mine, it took twenty days to get coal to the valley, via first the railroad to Victor, Idaho, and then a wagon over Teton Pass.) The mine was productive and remained open until the mid-1930s, at which time other sources of fuel became more economical.

“It’s easier to deal with tourists than cattle,” the ranchers are said to have joked with one another.

THE CLOSING OF the Jackson Coal Mine jibed with locals’ changing ideas about Cache Creek, which in 1905 had been included within the boundaries of the newly designated Teton National Forest. Not surprisingly, John D. Rockefeller, who later was responsible for the enlargement of Grand Teton National Park, was instrumental in the founding of the Teton National Forest. In his book A Contribution to the Heritage of Every American: The Conservation Activities, Rockfeller wrote, “The two reasons which have moved me to consider this project are: 1st, The marvelous scenic beauty of the Teton Mountains and the Lakes at their feet, which are seen at their best from the Jackson Hole Valley; and 2nd, The fact that this valley is the natural and necessary feeding place for the game which inhabits Yellowstone Park and the surrounding region.” Locals had begun to think not only about what they could take from the Cache Creek area, but what they could do to preserve it, even if their desire to protect the area was not entirely for environmental reasons.

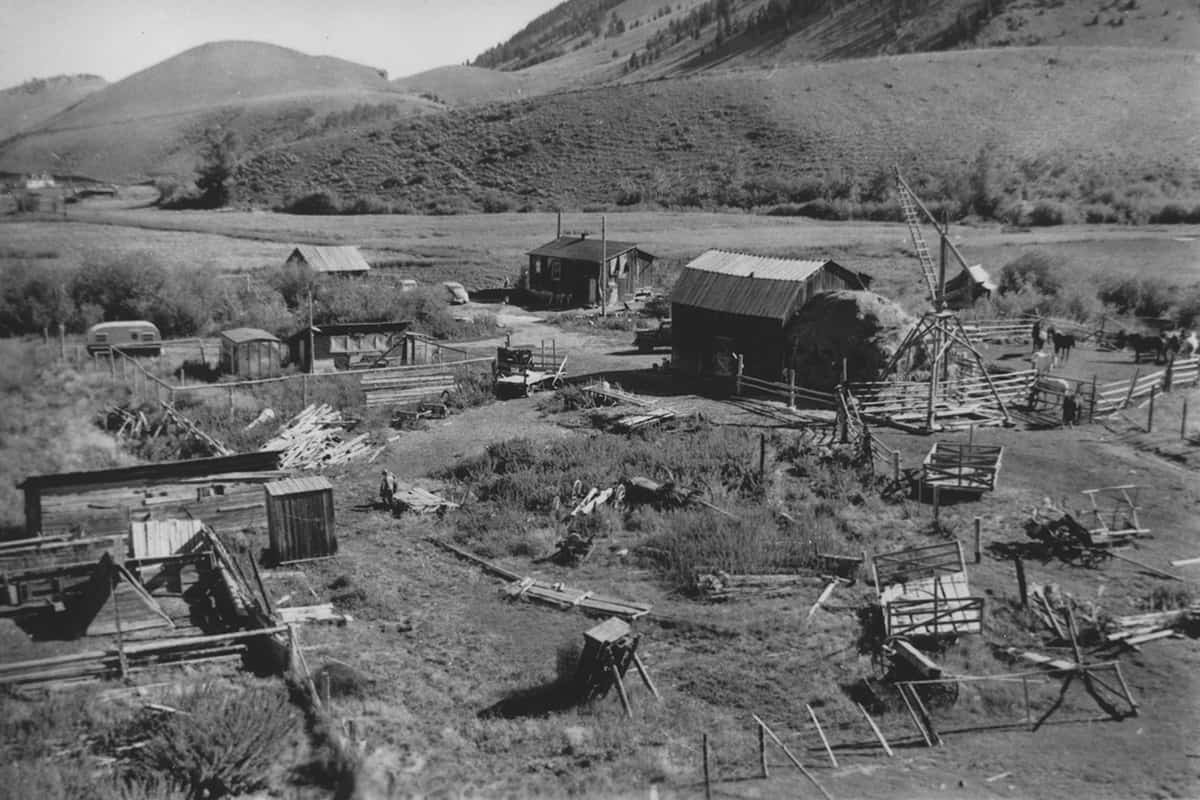

In the 1910s, ’20s, and ’30s, European royalty and wealthy easterners had begun to come to Jackson Hole to see the mountains and lakes Rockefeller wrote about, and to hunt the area’s populous wildlife. Local ranchers, who had long struggled to survive the valley’s short growing season and harsh climate, began opening their homes, for a fee, to these visitors. Jackson Hole had its first dude ranches. “It’s easier to deal with tourists than cattle,” the ranchers are said to have joked with one another. Dude ranches would bring guests on horseback rides into Cache Creek—a “wilderness” area close to town.

Cache Creek hunting camps were established, too. In the 1960s, Charlie Peterson got a permit to build a camp three miles up the creek. Welcoming hunters for years, the camp was bought in the 1990s by Joe Albright, who already owned Flat Creek Ranch, a luxury dude ranch tucked onto the banks of that creek several valleys north of Cache Creek. Albright had no plans to resurrect the Cache Creek camp though, and in 2000 the U.S. Forest Service removed it.

Of course, it wasn’t just for visitors that locals wanted to protect Cache Creek. There was the fact it was the town’s primary water source. This actually won out over recreation in the area: In 1942, the town government restricted public travel and intensive recreation, and halted all mining, forestry, and grazing in Cache Creek to ensure its health. In the 1960s, the road that was built for the Jackson Coal Mine was closed to all vehicles, upstream of what is today’s Cache Creek trailhead.

In the late 1950s, while Cache Creek was on recreation lockdown, a group of investors wanted to develop a major ski resort in Jackson Hole. Despite the restrictions on activity in the area, Cache Creek was the group’s obvious choice—it was on national forest land, had a wide array of terrain, and was right next to town. The investors hired two independent consulting firms to conduct studies about a Cache Creek ski resort; thankfully, both determined the area was not a suitable location.

In 1965, with the idea of Cache Creek Mountain Ski Resort dead and the town’s water finally coming from a well system, Teton National Forest Supervisor Bob Safran lifted the recreation restrictions in the area. (The Jackson Coal Mine road was kept closed, however.) Locals were happy to have their backyard wilderness playground back and didn’t take the area for granted anymore, as many had in the past.

“You think of using the public lands and the national forest for a sustained yield, but using the water resources, getting a few logs to build a house, permitting a coal mine that provided heat for the town, it’s very much of a utilitarian view. But it’s still public lands and making sure you’re not irreparably damaging anything,” says Linda Merigliano, the Bridger-Teton National Forest recreation manager, who has worked in and helped manage Cache Creek for nearly thirty years.

But Cache Creek’s biggest threat was still to come after 1965. Soon after the national gas crisis of 1973, The National Cooperative Refinery Association (also known as CHS, Inc.) proposed a large-scale oil and gas cultural resource survey of the area, extending all the way to Game Creek. Included in the proposal was a new road and access pad area at the base of the Noker Mine Draw. “This really riled people up in Jackson,” Merigliano says. “There was a sense that we’d been taking all these resources and developing for so long and enough is enough; there needs to be some balance here.”

With the help of the Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance, the Jackson community rallied and hired lawyer Bob Schuster to represent them against CHS, Inc., which soon abandoned its ambitions for Cache Creek.

Since CHS, Inc. was chased out of town in 1981, Cache Creek has been left alone in terms of large-scale development proposals. But the town’s population is growing, and more and more residents recreate in the area. While there’s little chance of oil and gas development happening in Cache Creek, hiking, biking, and horseback riding trails are being developed. In 1990 there were about forty miles of trails in Cache Creek. Today there are more than sixty miles. In 1990, approximately ninety-four people and thirteen dogs recreated in the area on any summer day; by 2017, that number had grown to 185 people (and forty-three dogs).

Still, “It’s a pretty wild place,” Merigliano says. And it’s a slice of living history.