Read The

Current Issue

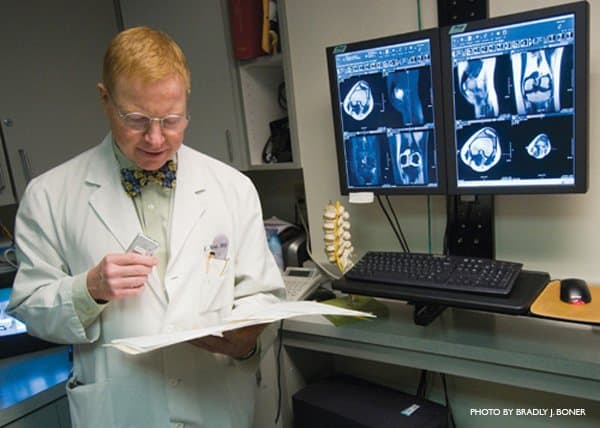

The Knee Guy

Dr. Peter Rork has repaired thousands of ACLs in his years as a surgeon.

BY KELSEY DAYTON

Peter Rork wanted to retire. He was ready, and he had a plan: No more new patients, unless they specifically asked for him. But Jackson wasn’t quite ready to let the man known for fixing knees close up shop. Neither was I.

Ten years earlier I tore my left anterior cruciate ligament, or ACL, as a high school tennis player. It’s a pop, a click, and a crunch; the burning sensation of ligaments separating inside—a pain you don’t forget. Now, at twenty-six, my days of competitive sports were long behind me, replaced with the common Jackson Hole inner drive to ski harder, climb higher, and generally move faster.

The snow on January 31, 2009, was soft but packed. Weaving around in the trees, we were moving fast—and then a little too fast. I cut in hard. I heard the pop and felt my knee rip apart. I knew.

Before I even reached the bottom of the mountain I had a plan. Healthy the past few years in Jackson, I knew few doctors. But even I had heard of Dr. Rork, the “knee guy.” In his twenty years as an orthopedic surgeon, he has made repairing ACLs his signature. As friends heard of my knee injury, the question was almost always the same: When are you seeing Dr. Rork? No one asked if I was going to any other doctor.

Rork was in his third year of medical school at the University of Maryland when he decided to become an orthopedic surgeon. He watched as a surgeon straightened a grossly deformed rheumatoid hand. “I had to be that guy,” he says.

“We have three machines around here that tear ACLs,” Rork says. “They are called Snow King, Grand Targhee, and the [Jackson Hole Mountain] Resort.”

His busiest month is usually March, when the snow can be iffy and people are often skiing aggressively, brimming with confidence toward the end of a long season. Rork set a “personal record” for a month in March 2008, with eighty-six ACL surgeries. His March average is down around fifty-eight. January is the second busiest month, when he averages fifty-five surgeries. That is followed by December, then February.

“There are two types of skiers,” Rork says. “Those who have torn their ACL and those who will.”

The doctor himself was lured west by the promise of mountain adventures. Today, he wears his downhill skis only when working with the U.S. Ski Team, for which he is one of about sixty staff doctors. He has patients of all ages and backgrounds. But Jackson breeds a common torn-ACL victim, Rork says; the place attracts a young, athletic, aggressive population. “They take a high-risk sport and push the envelope. And some don’t make it out without a knee injury.”

Rork’s patients are usually in their mid-twenties, but he has done ACL repairs on patients as old as sixty. Some have criticized him for doing surgery on a sixty-year-old—but, he says, he’s had patients who have waited their entire lives to retire to Jackson Hole, and they want to spend 110 days skiing in the winter.

My friend Lauren Whaley [who wrote the “Dining” piece in this issue–Ed.], a snowboarder at the time, tore her ACL learning to ski in 2006. Friends of Whaley’s who were climbing and skiing guides directed her to Rork. She knew little about him, other than that he had operated on some of her mountaineering and skiing heroes, like Alex Lowe and Doug Coombs. She didn’t care about credentials when she needed her knee fixed.

“I don’t want to see your resume,” she told Rork. “I want see athletes on the mountain who have gone to you.”

People warned her of Rork’s abrupt bedside manner. She didn’t care about that, either. “When you’re anesthetized and your knee is cut open, do you care if he’s coddling you, or if he’s deft and dexterous?” Whaley asks, adding that she never saw the harsh side of him she had heard about.

But indeed, Rork has a sharp, sarcastic sense of humor, and he isn’t one to waste words, says Lanny Johnson, a physician assistant. “To the patient, the benefit is he demands 100 percent of himself all the time. He pretty much pursues perfection.” Johnson, who has worked with Rork for about four years, says he’s never seen a surgeon so proficient with an arthroscope. “I think there are few who match his hand–eye coordination and speed and efficiency in the operating room,” Johnson says. “He’s a knee savant.”

As for me, I limped into Rork’s office two days after my skiing accident, waving to acquaintances I encountered on crutches or in knee braces. In the examination room, Rork felt my knee. Then he asked if I wanted surgery, saying that he could do it the next morning.

Rork prepares for a day of surgeries with characteristic precision. The night before, he’ll be in bed by 8:30 p.m. He awakens at 5:30 a.m., listens to the business report on National Public Radio, and is out of bed by 5:51. His first surgery is usually at 7:30 a.m., so he arrives at Teton Outpatient Services by 7:00.

Rork permits no talk in the operating room about anything other than the surgery at hand. There is no radio noise, or idle chatter. He doesn’t even have to ask for instruments, as the nurses know what he’s doing, what he needs, and what comes next. His eyes fix on the TV monitor to which the arthroscope transmits images of the joint he’s working on. He doesn’t even glance at the actual knee. A gloved finger digs into an opened-up leg and out come hamstring tendons which he will mold into a new ACL more than twice as strong as the original. After about twenty minutes he leaves, letting the staff sew up the leg as he ducks out to finish paperwork and dictate notes on the surgery before heading into the next one. He often runs ahead of schedule.

Rork says he has done about 12,000 surgeries in his career, approximately a third of them ACL repairs. A trip to the grocery store in Jackson can lead him to a dozen encounters with former patients.

Of the thousands of surgeries he has performed, Rork says one sticks out. He was on call when the well-known mountaineer and snowboarder Stephen Koch was wheeled into the emergency room at St. John’s Medical Center. Koch had been caught in an avalanche on Mt. Owen, and Rork says he’d never seen such a combination of injuries on a person still breathing.

Rork was Koch’s first choice for a surgeon. “I trusted him based on his reputation,” Koch says. “Having known so many people who have had successful surgeries by him—it wasn’t a question. That speed and skill is beyond perfection.” Koch was eventually able to return to the sports he loves.

During the 2007–08 ski season, Rork performed three hundred surgeries. He has repaired more than a dozen ACLs in a single day, his fastest taking approximately twenty-five minutes. He isn’t trying to beat the clock, he says, but the shorter the surgery lasts, the less time the patient is under anesthesia and the lower the infection rates. He understands Jackson patients, many of whom will try to bulldoze through rehab while Rork and physical therapists try to rein them in.

Last year, in preparation for retirement, Rork scaled back on surgeries, sending patients when he could to his partners and he himself performing fewer than forty ACL repairs. But the requests for him kept coming. And he realized that, even after all his years and all the surgeries, he still wasn’t tired of knees. Doing at least some of the surgeries seemed easier than pushing off the requests and retiring.

“It’s a conceptual thing,” he says. “I ‘get’ knees. And I like a good outcome.”