Read The

Current Issue

The Valley’s Greatest Secret?

The National Museum of Wildlife Art celebrates its thirtieth anniversary this year, and has been recognized by Congress and the American Alliance of Museums.

By Lila Edythe

THE OAKLEY QUARTZITE façade of the National Museum of Wildlife Art (NMWA) blends into the rocky hillside it sits on opposite the National Elk Refuge a couple of miles north of downtown Jackson. Combine this natural camouflage with the fact that “wildlife art” is a genre that, at best, is often misunderstood, and, at worst, is misinterpreted to be taxidermy, and it’s understandable that less than one in fifty visitors to the valley finds their way here. Just because it’s understandable, though, doesn’t mean it’s right.

“We’re the best-kept secret in Jackson,” says chairwoman of the museum board Debbie Petersen. Less biased visitors agree. Tourists in on the secret titled their reviews on TripAdvisor, “A hidden gem,” “A must-see,” “Great Collections,” “Beautiful art in a beautiful setting,” and “Glad we went!” Petersen says, “Secrets are great, but it’s frustrating. Visitors to this valley have no idea what they’re missing if they don’t understand what we have.”

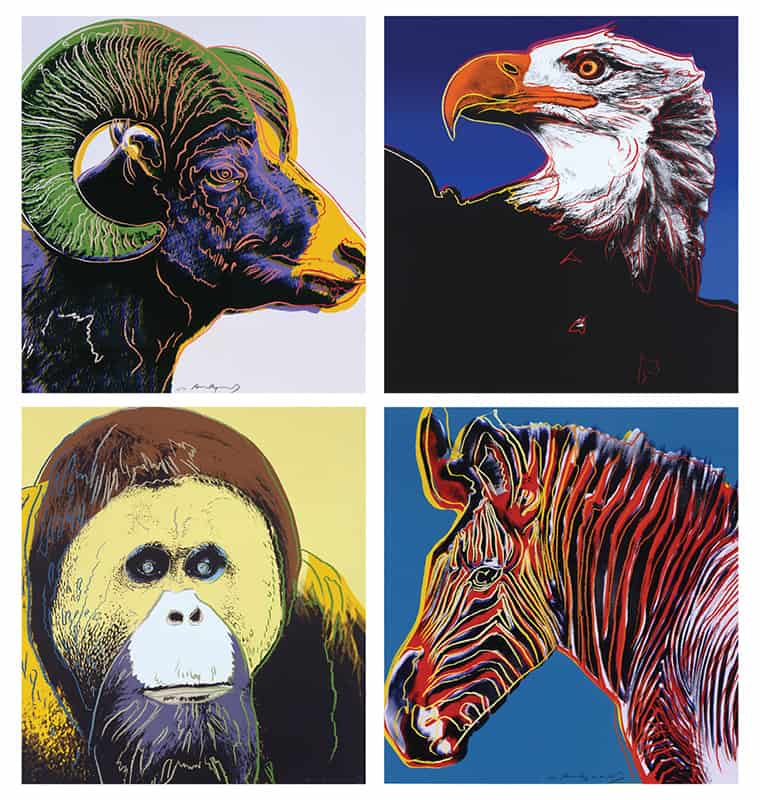

What the National Museum of Wildlife Art has is a permanent collection of more than 5,000 objects, from 2500 BC Native American birdstones to work by Thomas Moran, Carl Rungius, Albert Bierstadt, Georgia O’Keeffe, Maynard Dixon, Andy Warhol, and Paul Manship. (Manship’s sculptures Indian and Pronghorn Antelope are in the museum’s permanent collection, but you might know him better for his gilded, cast bronze sculpture Prometheus, which is on display in front of Rockefeller Center in New York City.) “One of the most often repeated visitor comments is about the breadth and scope of the collection,” says Dr. Adam Duncan Harris, the museum’s Petersen curator of art and research. “Almost everybody in the world has depicted wildlife.” The first time Petersen herself walked into the museum, years before she joined its board, she says she was “struck by the quality of the art. I did not expect fine art in a museum to exist in this valley. Walking in was explosive.”

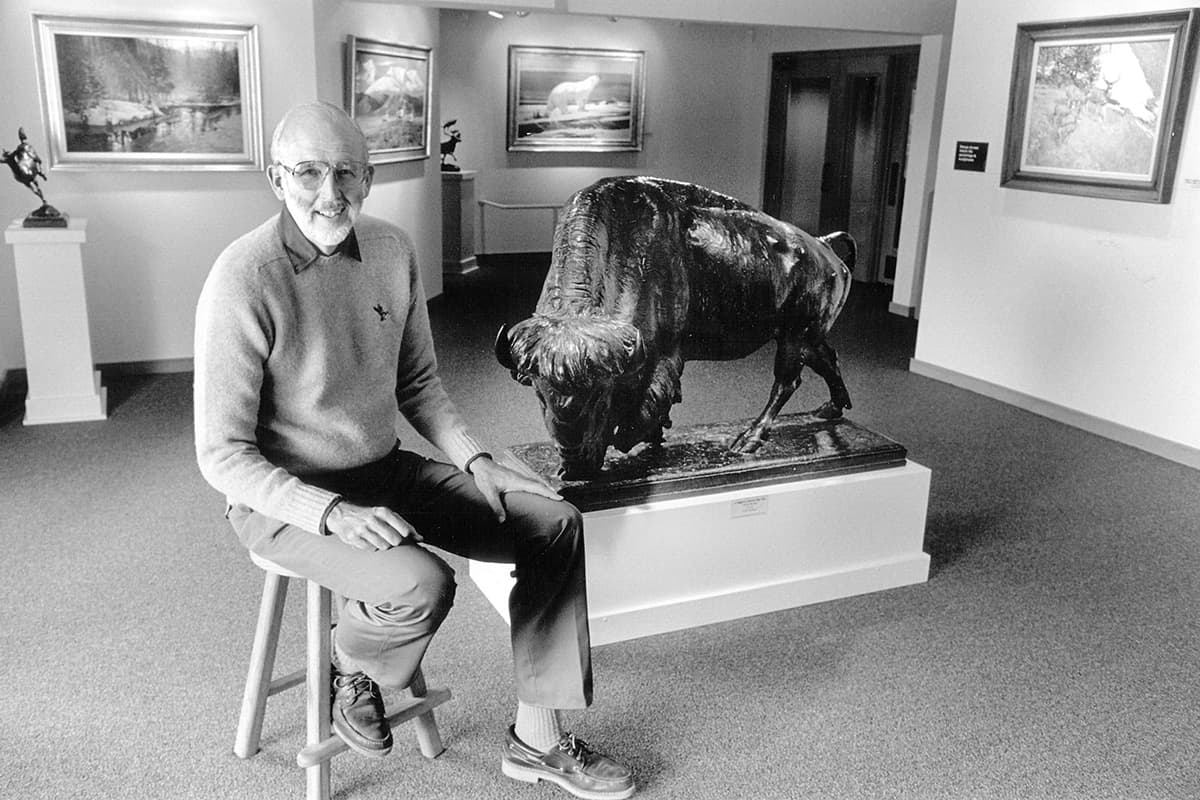

FOUNDED IN 1987 as the Museum of the American West in a 5,000-square-foot rented space on the Town Square, the museum’s original permanent collection was the personal collection of locals Joffa and Bill Kerr. Approximately 220 pieces of art were on exhibit. The museum moved to its current space, a building inspired by a sixteenth-century Scottish castle, and changed its name in 1994. Harris was hired as curator in 2000.

With Harris’ curatorial direction and a long-serving, dedicated staff and board, the NMWA, if a secret in Jackson Hole, has made itself known nationally in the art world. In 2002, the American Alliance of Museums (AAM) granted the museum accreditation, an honor less than 3 percent of the country’s 35,000 museums can claim. (The AAM reaccredited the NMWA earlier this year.) In 2008, Congress voted to recognize the museum as the “National Museum of Wildlife Art of the United States.” In the last ten years, eight exhibits curated by the NMWA have gone on to tour other museums across the country. In 2015, the museum’s sculpture trail, designed by Oakland, California-based landscape architect Walter Hood, hosted Chinese artist Ai Weiwei’s Zodiac Heads. Other museums that were part of the Zodiac Heads world tour were Prague’s National Gallery, Tuileries Garden in Paris, and the Smithsonian Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C. In 2016, Dr. Harris was one of three Wyoming residents to be awarded a Governor’s Arts Award by the Wyoming Arts Council.

In 2002, the American Alliance of Museums granted the museum accreditation, an honor less than 3 percent of the country’s 35,000 museums can claim. (The AAM reaccredited the NMWA earlier this year.) In 2008, Congress voted to recognize the museum as the “National Museum of Wildlife Art of the United States.”

AS AMAZING AS the NMWA’s collection and temporary exhibits are, the importance of the artwork is magnified by the museum’s location. “One of the most powerful things about the museum is that it is in the middle of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, at the bottom of this amazing wildlife corridor that stretches up to the Yukon,” Harris says. “It is such an appropriate place for a museum of this subject to be located. There’s this whole synchronicity between what is happening outside the building, the architecture of the building, and then what is happening inside.”

Visitors to the NMWA regularly report seeing and/or hearing elk, bison, coyotes, foxes, and bighorn sheep while walking from the parking lot into the museum. When I interviewed Petersen at the museum this past January, she apologized for being five minutes late. “I was here, but couldn’t bring myself to come inside,” she said. “I was standing outside listening to coyotes or wolves howling like crazy on the elk refuge.” There are few, if any, other places in the world where you can see a moose, bighorn sheep, bison, wolf, or elk in real life and, minutes later, walk into a museum and see renderings of that same animal by a diverse group of artists working in a range of styles and from different time periods.

THE MUSEUM PLANS important temporary exhibits for every summer, but the three major exhibitions hanging this summer, during which it’s celebrating its thirtieth anniversary, are particularly noteworthy: Andy Warhol: Endangered Species; Photo Ark: Photographs by Joel Sartore; and Iridescence: John Gould’s Hummingbirds. “I was spellbound the first time I saw Joel’s Photo Ark images,” Petersen says. Petersen first saw Sartore’s images at the National Geographic Museum in Washington, D.C. “As soon as I saw it, I was amazed and felt it was an exhibit that was made for us, not only because it was Joel Sartore—who is no stranger to us as someone who has previously had a one-man show here—but because it’s about the multitude and diversity of endangered animals.”

Petersen immediately spoke with Kathryn Keane, National Geographic’s vice president of exhibits. Even though a curated selection of Sartore’s Photo Ark images had never before been exhibited outside of the National Geographic Museum, “Kathryn got it,” Petersen says. “She knew our museum and agreed absolutely that the Photo Ark needed to come here.” Dr. Harris says, “It is an honor to be one of the first venues to host this exhibit after it premiered at the National Geographic Society.”

While the Sartore photographs are on loan, the eighty prints that make up Iridescence: John Gould’s Hummingbirds are now part of the NMWA’s permanent collection. Harris says, “These pieces are the reason why you can’t not answer your phone.” A Colorado collector called Harris and, “He said, ‘I’ve got eighty hummingbird prints from John Gould from the 1800s. Do you want them?’ I was like, ‘We’d love them!’ ” Harris recalls.

In 2014, the museum did an exhibit, Parade of Plumage, which was entirely of one artist’s (Francois-Niçolas Martinet) engravings. “It really resonated with visitors,” Harris says. “Having this many pieces on exhibit at the same time from the same artist gives you an amazing sense of their artistic capability.”

The curator and preserver of the Zoological Society of London, Gould had a sixty-year career in ornithology, during which he worked with a number of artists to produce approximately 3,000 plates of birds. Gould spent twelve years working on A Monograph of the Trochilidae or Hummingbirds. This monograph was completed in 1861 and includes 280 plates in addition to the eighty in this exhibition. Harris says the Gould and Sartore exhibits “complement each other really well. Both are cataloguing projects. One shares knowledge about new species with the public, while [the other] one is on the opposite end, trying to bring to light the plight of animals in trouble.”

And then there’s Andy Warhol’s Endangered Species portfolio. “One of the main goals in almost any installation we do is to show people that what they think wildlife art is, is not necessarily all that it is,” Harris says. “I love hearing that people are surprised by what we have.” Harris isn’t speaking specifically to this Warhol exhibit, but he might as well be. None of the four local friends I poll know that: (1) Andy Warhol did a series of paintings of animals; or (2) this series, Endangered Species, has been part of the NMWA’s permanent collection since 2006. Harris says, “These fall into the same category as our Georgia O’Keeffe painting. Visitors come in here assuming they are going to see one kind of art, and then they realize the diversity of what we have and are astounded.”

$14/adults, $12/seniors, $6/kids; open daily from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., 2820 Rungius Rd., 307/733-5771, wildlifeart.org

30th Birthday Events

Andy Warhol: Endangered Species: May 17 to November 5

Photo Ark: Photographs by Joel Sartore: June 10 to August 20

Iridescence: John Gould’s Hummingbirds: May 27 to August 27

Plein Air Fest, Etc.: 10 a.m. to 3 p.m., June 17, free

Black Bear Ball: 6 p.m., August 19, tickets $375