Read The

Current Issue

What a Hoot

A weekly open mic night, the Hootenanny is as much of an adventure for the audience as for musicians.

By Isa Jones

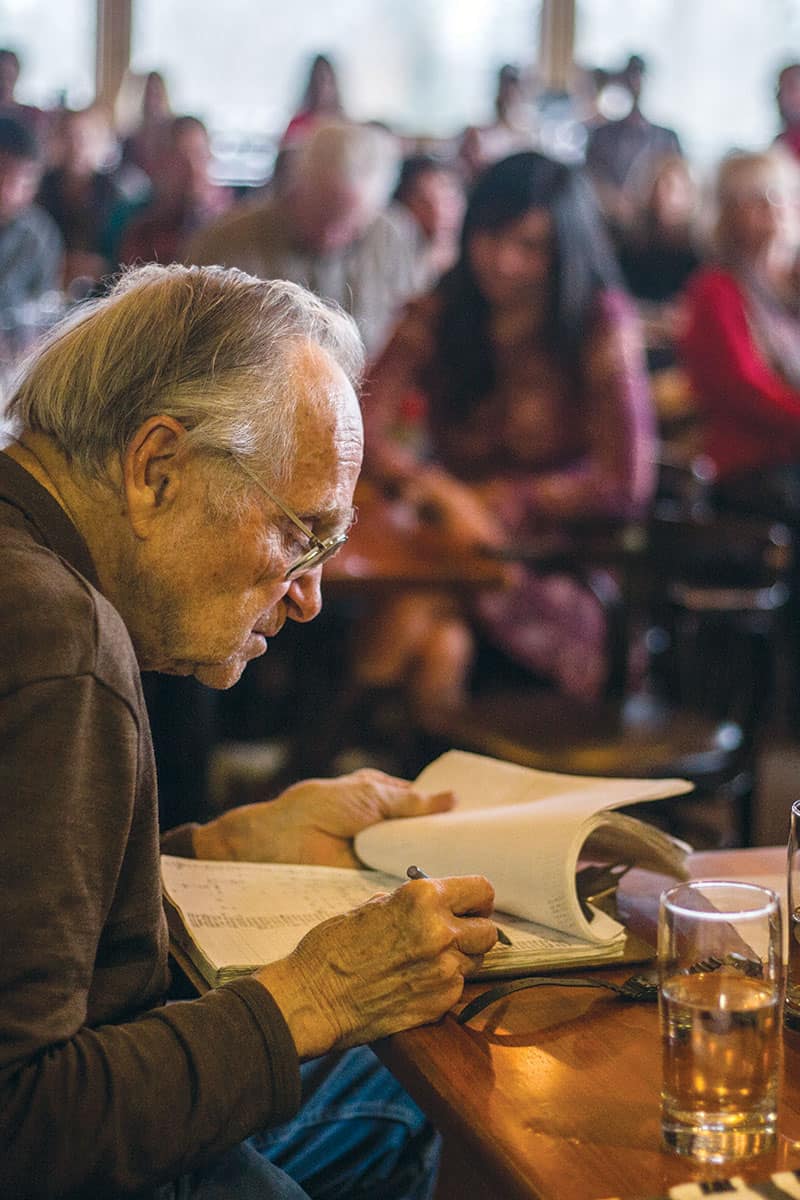

BEFORE THE HOOTENANNY was “the Hootenanny,” it was a secret meeting around a fire under the Moose bridge in Grand Teton National Park. That was in the 1950s, and it was called the “Teton Tea Party.” Bill Briggs, the famous mountaineer and skier, organized and led it. “It” was a few friends strumming acoustic guitars, with Briggs playing the ukulele, under the star-filled Wyoming night sky.

That lasted until the early 1990s, when Briggs and friends’ Teton Tea Party changed names to the Hootenanny and moved from under the bridge. But it didn’t move far. The Hootenanny takes place at Dornan’s in Moose, which is just around the corner from the bridge over the Snake River where it started. For years, it was known only by those who participated, but today the open mic night draws crowds of both performers and spectators. And there’s the occasional celebrity drop-in.

On any Monday night—inside Dornan’s Pizza Pasta Company in fall, winter, and spring, and outside next to Dornan’s Chuckwagon in the summer—musicians and spectators from near and far gather. The audience is usually from farther away than the musicians, though. Any musician is welcome to put his or her name in the can for a random chance to play, but week after week it is often the same ones—John Kuzloski, Sally McCullough, Jenny Landgraf, John Carney, Dan Thomasma, and Adrienne Ward are all locals and Hoot regulars—albeit often in different permutations. You’ll find solo musicians on the Hoot’s modest stage—carpet-covered plywood in front of the fireplace at the east end of the dining room—but more often it’s duos and trios. And usually these groups come together right before they go on. One evening I’m there, Hank Phibbs plays his Dobro guitar with no fewer than four different configurations. A musician “will ask a friend or two to play with them,” says John Byrne Cooke, a musician who played his first Hoot in 1993 and is now on the Hoot’s board of directors. “It’s all so informal.”

And that’s part of what makes it so special. Tales of the uniqueness of the Hoot spread to legends John Denver and Chuck Pyle. Both of these men, separately, heard of the Hootenanny from acquaintances. Neither could resist the chance to stand in front of an unsuspecting crowd and belt out a tune. But mostly, the Hoot is about the community. The best proof of this is from 2003, in the form of Mardy Murie. Nicknamed the “grandmother of the conservation movement,” Murie was a legend. She helped pass the Wilderness Act and create the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. She was also a longtime attendee of the Hoot, barely ever missing one.

But in 2003, she was too ill to attend. So one Monday, the Hootenanny came to her. “About a week before she died was the last time we went to play for her,” says Phibbs, a board member who played his first Hoot in 1993 and still plays about three of them a month. “She was beyond speech, but as soon as we started tuning, her eyes snapped open. It was like playing to a spirit; it reached beyond speech to something real deep.”

“Generally, songs at the Hoot are from the folk, country, old-time, bluegrass, and self-written traditions,” Cooke says. But nothing is off-limits.

SINCE AROUND 2000, the number of musicians wanting to play the Hoot has exceeded the concert’s three hours. “We were no longer able to guarantee everyone two songs,” Cooke says. “We had extensive board meetings about it. Do we give everyone one song? Or do we maintain the two songs because it’s like a miniset?” The board decided to stay with two songs and instituted the “old can” method. Musicians that want to play put their names in a can. The MC (Briggs usually handles this duty) pulls out names at random.

What you’ll hear any night is pretty random, too. There are original songs as well as covers. “Generally, songs at the Hoot are from the folk, country, old-time, bluegrass, and self-written traditions,” Cooke says. But nothing is off-limits. “At a recent Hoot, we expanded the range. A regular performer brought a musician from Kenya, who played [the guitar] in traditional dress, accompanied by four Hoot musicians. In the same set, Jack Sallee, who visits every summer from Tennessee, brought out not his five-string banjo but his flamenco guitar, at which he is quite adept.” Bassist Mark Memmer is sometimes accompanied by a friend on jazz trumpet. The only amplification is a single microphone. There is no soundcheck. It’s the open mic of every romantic, music-obsessed coffee shop owner’s dreams.

And also of musicians’ dreams. “People do not talk when people are on [the Hoot] stage, which is unheard of in a bar,” Phibbs says. The only sound you hear from the Hootenanny outside of the strums of guitars and vibrations of vocal cords is the host announcing who is next on stage.

“It’s the chance to both play with other people and hear other people,” Phibbs says of the intent of the Hootenanny. “This valley is full of remarkable musicians. The opportunity to both share music with them and hear so many different musicians perform has been continually magical for me. I never tire of it.”

THE INSIDE (WINTER) Hoot is a different scene than the summer one in a pavilion next to Dornan’s Chuckwagon. There are two walls of windows behind the bar in the Pizza Pasta dining room, but, since it’s pitch black by 6 p.m. when the Hoot starts, you can’t see the Tetons at all. And even if it wasn’t dark, chances are the range would be obscured by falling snow—Moose gets several more feet of snow every winter than downtown Jackson. Through intermission, the kitchen to the right of the stage is cranking, and a line of people waits at the cash register in front of it to order dinner. (The spinach-artichoke dip is a great starter, and you can’t go wrong with any of the pizzas.) All of the tables and chairs are full. There might be an open stool or two at the bar. People wander between the dining room and the attached wine shop, which has been recognized numerous times by Wine Spectator as one of the best in the state. About two-thirds of the audience are regulars; the rest, like John Denver and Chuck Pyle, are here because they heard about it from friends (or maybe read about it in this magazine). Even before the music starts, it’s all very cozy. Then the music begins, and it becomes a night you can’t experience anywhere else.

The Hootenanny runs from 6 to 9 p.m. every Monday night at Dornan’s; free; 12170 Dornan Rd., Moose; 307/733-2415