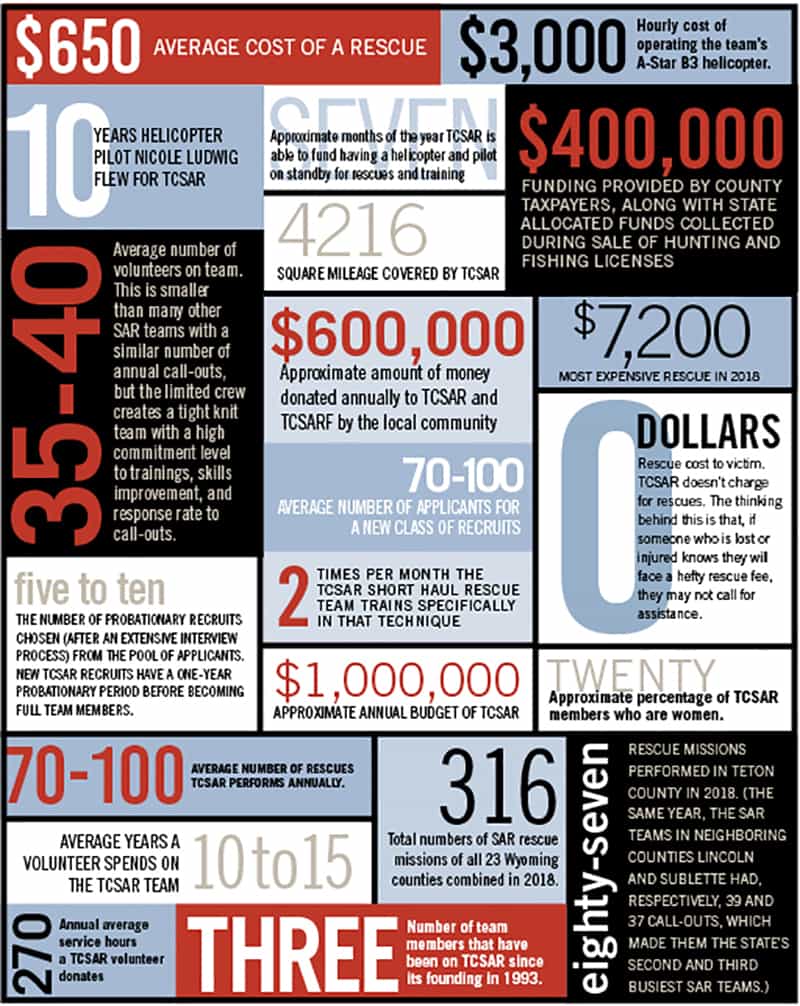

Read The

Current Issue

Who You Gonna Call?

Teton County Search & Rescue team members would never say this, but they’re one of the busiest and best mountain SAR teams in the country.

By Brigid Mander

Search & Rescue operations for two missing backcountry skiers in Grand Teton National Park. Photo by Bradly J. Boner

IN THE LATE morning on May 29, 2019, the Teton County Sheriff’s Office (TCSO) received a 911 phone call. A skier had fallen off the back of Cody Peak, outside of Jackson Hole Mountain Resort, and sustained serious injuries. The dispatcher determined the call was 1. a backcountry accident and 2. within Teton County, so she immediately paged the eight-person advisory board of Teton County Search and Rescue (TCSAR) and also Teton County Sheriff Matt Carr. At 10:47 a.m., the pagers of TCSAR chief advisor Cody Lockhart, medical advisor Dr. AJ Wheeler, logistics advisor Phil “Flip” Tucker, planning advisor Galen Parke, membership advisor KC Bess, training advisor Anthony Stevens, and TCSO SAR supervisor Jessica King all went off. Within minutes, the board members who were in town convened on a conference call to assess the next steps.

Since there was a confirmed victim, and it was confirmed they were unable to self-rescue, the board decided to page out (via texts on cell phones) the rest of the all-volunteer team. The texts included the accident location and key details, and also alerted team members as to the radio and communications frequency that would be used for this rescue and identified the incident commander (IC): Jessica King. (The communications frequency changes based on the repeater location closest to each incident; the IC changes on each call-out so it’s not always the same small group of people in charge.)

In less than 15 minutes, 18 TCSAR members were at the group’s headquarters, which includes a helicopter hangar. The 15,000-square-foot building, completed in 2010, is just off Highway 22 near the “Y” intersection. Rescuers came from their jobs, which are wide-ranging: non-profit employee, doctor, teacher, IT worker, contractor, financial advisor, lawyer, and firefighter, among others.

King assigned volunteers to different roles. For this rescue she needed a short-haul team, a team to drive the TCSAR truck to a staging area as close to the accident as possible, and a team to stay at the hanger and monitor communications. And TCSAR wasn’t the only group responding to this rescue because the victim had set out from Jackson Hole Mountain Resort (JHMR Ski Patrol jurisdiction), hiked out of the resort into Teton County (TCSAR jurisdiction), and then had fallen in Grand Teton National Park (GTNP jurisdiction). This could make things complicated, but, because it’s not unusual for jurisdictions to overlap in this valley, TCSAR, JHMR Ski Patrol, and GTNP regularly train together so when situations like this rescue arise, they can work together seamlessly.

About one hour after the page went out to the entire TCSAR team, one of volunteers in the helicopter spotted the victim. It was decided to use the chopper to evacuate the victim via short-haul rescue technique. By 2:35 p.m. the helicopter, with the victim safely secured in a litter suspended beneath it, was at the base area of JHMR. The litter was quickly unhooked and the victim loaded into a waiting ambulance headed to St. John’s Medical Center. And then SAR members went home, or back to work.

TETON COUNTY’S SEARCH and rescue team, an all-volunteer force of highly skilled, community-minded people with special training, is the state’s busiest and most esteemed SAR team.

Annually, it responds to between 70 and 100 incidents. The team is more than twice as busy as the state’s next busiest SAR team, which is usually neighboring Sublette County Search and Rescue. TCSAR is on call 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, responding to call-outs for missing, injured, and deceased hunters, hikers, climbers, skiers, rafters, snowmobilers, and bikers. If a backcountry user needs help, TCSAR is it. The team has even located planes crashed in the backcountry and cars that have driven off Teton Pass.

The State of Wyoming charges the sheriff’s office in each of its 23 counties with providing search and rescue services. Funding comes from county tax coffers, as well as from the Wyoming Search and Rescue Council, which allocates money from sources like hunting, fishing, boating, and snowmobile licenses. (Purchasers can opt to donate $2 to the state SAR fund.) TCSAR’s annual budget is about $1 million, more than half of which comes from the Teton County Search and Rescue Foundation, a non-profit founded in 2006 to support the team.

(SOME) OF THE GEAR

1. One of the most crucial pieces of equipment, an Airbus AS350B3 (aka A-Star B3), is leased for between seven and eight months annually. This model is known for its maneuverability. It is crucial for the team to have a helicopter on hand for winter rescues to extract injured people as quickly as possible from dangerous and/or hard-to-access mountain areas and situations.

The B3 is new for TCSAR this winter; for the prior 10 years, it used a Bell 407 piloted by Nicole Ludwig. Steve Wilson pilots the B3 and, like Ludwig, is among the few pilots with the skill set TCSAR requires: shorthaul and long lining, and flying in mountains and in extreme winter weather.

2. Polaris Magnum 500s and Polaris Sportsman X2 570s make up TCSAR’s ATV fleet of four. The team also recently purchased a four-seat Polaris RZR. All of these off-road vehicles are used for summer and other non-snow backcountry rescues.

3. A swiftwater jet boat uses a jet motor rather than a propeller motor. These work well in smaller rivers because they are able to operate in much shallower water than prop motors. Jet boats can get up ‘on plane’ across the surface of the water, which allows for fast and efficient travel, and they are highly maneuverable.

Two catarafts assist TCSAR on shallower rivers like the Hoback, or on braided sections and channels of other rivers, but don’t have the power to go against the current (i.e. upstream). One of the team’s catarafts is a Polaris Spirit Inflatable; the other is a Wooldridge Alaskan XL.

Photo by Ryan Dorgan

4. TCSAR has two Ford F-550 trucks, each equipped with a custom topper designed to accommodate rescue gear and medical equipment. Each truck cost about $38,000, and the custom toppers, which include built-in computers, screens, and electronics, were about $85,000 each.

Photo by Rebecca Noble

5. TCSAR has ten top-of-the-line, Polaris and Ski-Doo 800cc and 850cc engine, long-track snowmobiles. These are high-powered and nimble, and allow rescuers to access just about anywhere a member of the public could get in trouble on skis or on a snowmobile. TCSAR has hired Alpine, Wyoming-based professional snowmobiler and instructor Dan Adams to bring his Next Level Riding Clinics to Jackson for team members.

Photo by Ryan Dorgan

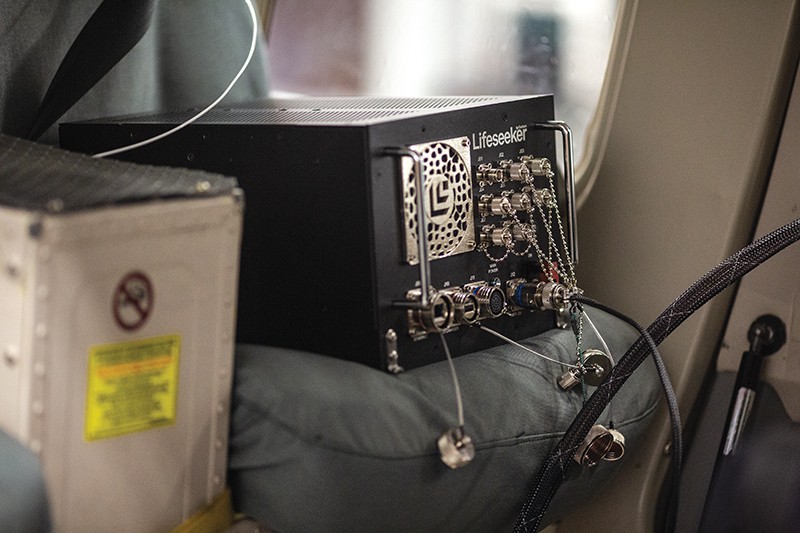

6. The Lifeseeker airborne system functions as a portable cell tower, giving people who are lost or injured in areas where there isn’t standard cell service (which is most mountainous areas around the valley), a signal they can use to call 911 and communicate with rescuers. TCSAR is the first organization in North America to use this technology. An anonymous donor gifted the team about $100,000 specifically so it could purchase the system.

Photo by Ryan Dorgan

TCSAR PROFILES

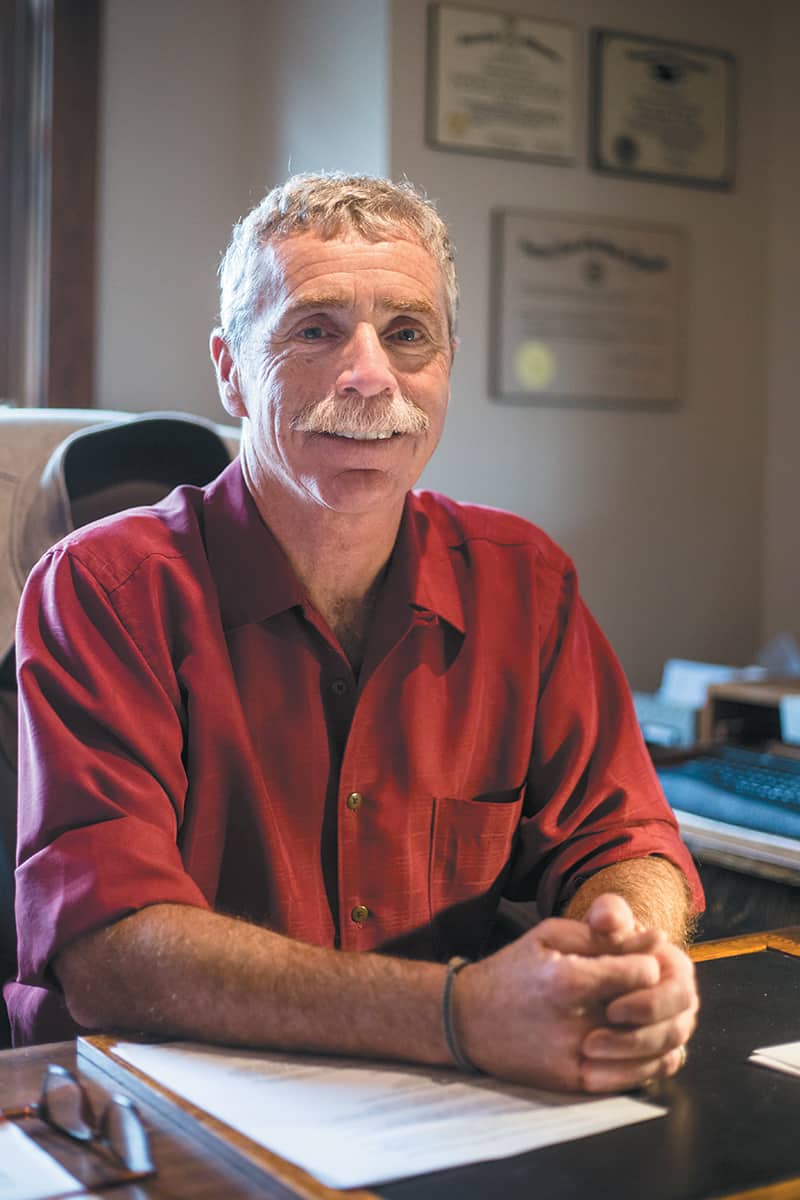

CHRIS LEIGH

PARIS-BORN, CONNECTICUT-raised Chris Leigh found his way to Jackson in the late 1970s. When offered a job in a local ski shop, he embraced post-collegiate ski bumming. “Those were the days of 100-day ski seasons,” he says. In the mid-eighties, Leigh left the valley to attend law school, and returned to Jackson in 1988 with a law degree. Around 2009, by which time Leigh was as accomplished of a mountain athlete as he was an attorney (he had founded his own criminal defense firm), a friend suggested he’d be a good fit for TCSAR. “I applied, I made it, and I’m humbled I made it,” says Leigh, now in his early sixties. “The selection process is not easy. It’s an incredibly tight team, with a lot of internal and external community support.” The commitment is significant, and family support is integral, he says, noting he could not be on TCSAR without his wife Mari Auman’s full support. After more than four decades in Jackson Hole, skiing is still Leigh’s main connection to the outdoors and a family activity. “Being athletic and having an outdoor mind is a component, but with SAR, it’s not about you. It’s about the team, and we are all a cog in the wheel.”

CODY LOCKHART

A TYPICAL OUTDOORSY Jackson kid from a ranching family, Cody Lockhart, 36, applied to TCSAR in 2009. “I had a friend on SAR who was always telling stories about helping people in the mountains,” he says. “It was inspiring, and I thought my skill sets could be useful to the team.” Lockhart made the cut and today is TCSAR’s chief advisor and responsible for overseeing the team and advisory board in partnership with the SAR supervisor (currently Jessica King).Lockhart’s day job is at Wind River Capital Management, a financial services firm he founded. He says it is tough to balance the commitment SAR requires with this job and a full home life with his wife Shauna and their two young children. “I definitely have phone anxiety,” Lockhart says. “I don’t go anywhere without it, in case a call comes up.” But the rewards dwarf any downside: “SAR has become like my second family, and social group. It’s a big honor and big commitment, but you just do it, you make it balance.” Lockhart is proud and grateful that the team has the funding and the training resources to constantly improve and provide better rescue services to people in Teton County. “We have so much knowledge and experience to solve these problems, and help people [who are] having the worst day of their lives. And our efforts have saved lives. To look a person in the eyes after we’ve helped them, nothing can compare to that.”

JENN SPARKS

A SKIER ORIGINALLY from Vermont who turned Jackson local in 1989, Jenn Sparks came from a family that highly valued community service. In 1998, when she wanted to give back, she looked to SAR. Twenty years later, the evolution has been enormous. “It’s so different now. When I joined we had to buy our own gear. It was a plus if we even got gas money!” she says. Today’s training and the gear at the team’s disposal are thanks to increasing support and appreciation from the community, and it puts their work on a new level, Sparks says. Now, with a day job in finance, a husband, and a teenage daughter, she also counts on her family’s support so she can continue to contribute to the team. The biggest lesson Sparks has taken from her 21 years of helping others, is that SAR is a selfless but enriching responsibility that provides an outlook that could be applied to all aspects of life. “Our job is [to] go out and help and not judge anyone’s decisions,” she says. “We prepare for everything, and it always takes longer than you think.”

RESCUED

IN MARCH OF 2018, Bart Monson, an experienced local snowboarder and mountain athlete, was ascending Mt. Taylor, a 10,352-foot-tall peak on the west side of Teton Pass, with three partners. The group had already skied a pitch of boot-deep powder on the mountain’s west face. To continue their descent, they decided to traverse to a more southerly aspect. Monson, 48, was the first to traverse, and, as he crossed a gully, he triggered an avalanche and was caught. In a couple of seconds the slide carried him about 100 feet downslope. The avalanche smashed him into a tree and Monson made a grab for it. He caught it, which saved him from being carried farther down the mountainside. “The impact with the tree was a horrible moment, but then I realized I wasn’t buried and it wasn’t the worst thing,” Monson says. But he knew his leg was broken (he later learned he’d broken his tibial plateau). One friend carefully navigated over to him and assessed his injury. Self-rescue was discussed, but it would have taken many hours to descend the rest of the peak, and the snow was increasing in instability. Also, Monson was in excruciating pain, which made any movement difficult. “We were lucky we had a [cell] signal. Being able to get SAR on the line is the best thing ever,” he says.

Because of Monson’s precarious location, TCSAR chose to short-haul him. “I had the most scenic, sub-zero, 90-second heli ride ever; the efficiency and seamless work of the team was incredible,” he says. “I [was] lucky the weather was good and that we have rescuers willing to put it on the line to come get people. But SAR and rescue don’t exist by chance; it’s not a right to get rescued, it’s a privilege. Since that day, I’ve had the most incredible feeling of gratefulness that we don’t always have in life.”

1993: Teton County Search and Rescue forms as a non profit. Prior to this, the sheriff’s office responded to calls about people missing and/or injured in the backcountry, but the number and complexity of rescues were growing beyond the office’s capacity, training, and scope.

2000: Because TCSAR does not yet have the funding to permanently lease a helicopter, part-time valley resident Harrison Ford had begun offering the team his personal helicopter to use on a rescue-by-rescue basis. This year, the celebrity himself is the co-pilot during the rescue of an ailing hiker in the Tetons and the incident receives widespread media attention.

2010: After decades of being based out of the sheriff’s office and a county storage facility south of town, the team gets it own headquarters and operations base, a 15,000-square-foot building just west of town on Highway 22. Within the building are classrooms and meeting spaces, lockers, a helicopter hangar, and a giant garage, among other features.

2012: To meet the increasing needs of the team for safety equipment and training, TCSAR Foundation forms.

2012: A helicopter accident on Togwotee Pass kills TCSAR member Ray Shriver and injures pilot Ken Johnson and team member Mike Moyer. The accident marks the first (and, to date, only) time a team member is killed during a rescue call.

2018: TCSAR celebrates 25 years of service

EDUCATION AND OUTREACH

Teton County Sheriff Matt Carr and TCSAR supervisor Jess King work with Jackson Hole High School students on backcountry rescue techniques in Grand Teton National Park. Photo by Ryan Dorgan

The TCSAR Foundation (TCSARF) runs several education and awareness programs to help people learn how to self-rescue and ways to stay out of trouble in the first place.

According to its website (backcountryzero.com), “Backcountry Zero is a Jackson Hole community vision to reduce injuries and fatalities in the Tetons. Backcountry Zero is a four-season, cross-sport, community-led program created by TCSARF to inspire, educate, collaborate, and foster leadership in order to develop and heighten awareness for safer practices in the backcountry. Backcountry Zero aims to cultivate a culture among user groups with a common language of principles that guide safer, enhanced decision-making and travel in the backcountry. These aims are accomplished through working with the community (guides, teachers, mentors, retailers) to create program touchpoints, and through crafting and implementing events, educational opportunities and workshops, granting programs, and shareable multimedia.” TCSARF founded Backcountry Zero in 2015.

What’s In Your Pack are hands-on classes TCSARF conducts every summer and fall. The classes usually cost about $20 and explore seasonal preparedness and backcountry safety.

Annually in the fall TCSARF holds the Wyoming Snow and Avalanche Workshop (WYSAW) and the Industry Professionals Workshop. The former is at the Center for the Arts and meant to be informational for snow enthusiasts from all backgrounds—backcountry skiers, snowboarders, Nordic skiers, and snowmobilers. Topics discussed include what it takes to stay safe in the backcountry, snowpack analysis, human behavior and decision-making, and risk versus reward, among other topics. JH

On many calls TCSAR responds to, rescuers put themselves at risk to help others in dangerous situations. On February 15, 2012, when responding to a snowmobile accident on Togwotee Pass, the TCSAR helicopter went down in high winds. The crash fatally injured team member Ray Shriver, who his peers say was a selfless teammate, mentor, and gifted search-dog handler. Shriver was one of the team’s founding members. The Shriver Society was founded in his honor and is is available to anyone donating any amount for at least three consecutive years. tetoncountysar.org/shriversociety