Read The

Current Issue

Yurt Life

In Kelly, more than a dozen people live in yurts. But the housing style is the least interesting thing about this small community, which has been going strong since 1981.

By Whitney Royster

photography by Ryan jones

IT’S 15 BELOW zero at a home in Kelly. The air cracks. Any moisture in it has crystalized. Outside, nothing moves. The home’s door—the link between inside and out—doesn’t move either; it is frozen shut. Prayer flags are stiff, frozen in midflap.

The walls of the home, which are fabric not wood, are solid like boards. To get to this home’s bathroom requires a journey not only out from under the covers, but out the frozen door. Get the door unstuck, and the bathroom is still a 200-yard walk—on a frozen path. It’s a lot of frozen.

This may sound like winter camping, but it isn’t. Not really. This is a full-time home. Yet this home is a 450-square-foot round yurt. It has rafters, windows, a wooden front door, a real bed, and a small kitchen. The owners’ clothes are scattered about, and there is a couch, and even a computer and printer. This yurt does not have running water or an electric heater; heat comes from a wood-burning stove.

Welcome to the Kelly Yurt Park, thirteen yurts with nineteen residents on the south side of the Kelly Road adjacent to the Kelly Elementary School and in the shadows of the Cathedral Group and Sleeping Indian. The yurt park, like the rest of Kelly, is an inholding within Grand Teton National Park. When the park was founded, Kelly was grandfathered in as a small enclave of private ownership. Today, Kelly has a population of fewer than 200 people.

YURTS ARE TRADITIONAL dwellings that nomadic people in Central Asia, primarily Mongolia, have used for centuries. They are circular, tent-like homes. Today they are made from all-weather vinyl fabric, but traditional ones, and most of the ones you’ll still see on the steppes of Mongolia and Kyrgyzstan, are made of wool or animal skin. Yurts are among the world’s first mobile homes; they are portable but stable, comfortable, and durable enough for longer-term living. A yurt is supported by rafters radiating out from a top dome and lattice work on the sides. A cable wraps around the top of the lattice and attaches to the rafters of the roof to hold the structure together. While Central Asians still move their yurts seasonally, the yurts in Kelly don’t move.

In 1981, Lyn Dalebout was twenty-six and working as a poet, writer, and bookseller in Jackson. Her sister, Jan, also in her twenties, was a nurse at St. John’s Hospital (now St. John’s Medical Center). They lived in Kelly—Jan in a “regular” house and Lyn in a yurt next door. Jan put the yurt up after living in a similar structure in Alaska in the late 1970s. The Dalebouts’ neighbors, Don and Gladys Kent, had a twenty-two-acre property and ran it as a seasonal campground. The sisters wanted to lease this land year-round for yurts.

“It was just this idea of wanting to live in a yurt,” Lyn Dalebout, now sixty-two, remembers. “Who knows where these great ideas came from? It was an organic process.” The sisters didn’t have a vision for a community, she says, but wanted yurts for themselves. They approached the Kents, who quickly agreed. Dawn Kent, Gladys and Don’s daughter, remembers her parents being very supportive of the idea of a yurt park. “For my folks, it was low-maintenance,” Kent, now in her sixties, says. What also appealed to Gladys was the connection to young people in Kelly. “She enjoyed the young people, because it really is not a place for older people, going back and forth to the bathhouse,” Kent says. And her mother felt keeping younger people in town would help “keep the community of Kelly alive.”

Gladys was born in Kelly. Her family, the Mays, were among the first settlers in the valley, homesteading on Mormon Row in 1896. In 1925, when the north side of Sheep Mountain collapsed in a giant landslide, slid into the Gros Ventre River, and created a 225-foot-tall dam that was half a mile wide, Gladys was seven. Two years later, the dam broke, and the Gros Ventre River washed away most of the town of Kelly, including the homes of forty families, and killed six people. Up until this time, Kelly was a bustling commercial hub in the valley. After the flood, though, Kelly struggled to maintain a population; keeping people there was important to Gladys her entire life.

Gladys’ innate creative spirit also embraced the idea of a yurt park. “My mother loved to talk to other people about all different sorts of ideas,” Kent says. “That’s the type of person who lives over there.” With the Kents’ agreement to rent them the land, the Dalebout sisters asked their parents for help.

“Our parents supported the vision, and bought us the commercial sewing machine to sew the yurts and also some of the construction material,” Dalebout says. “There were no commercial yurt companies at the time.” The yurts took two months to make. (Today, they can be bought online. A basic 450-square-foot yurt costs about $9,000. Add on wind and snow protection, roof and wall insulation, and a stovepipe outlet, and the total can run up to about $14,000, depending on size.) The Dalebouts made their yurts of canvas, and insulated them with hay. The hay used to rot during the winter and was replaced every spring.

In 1981, the sisters were the entirety of the yurt park. The next year, someone asked if they could set up a teepee. Over the years more and more people—friends of the Dalebouts and friends of friends—came, asking if they, too, could set up and live in the yurt park.

MOVING INTO THE yurt park today is similar. When a resident moves, the remaining yurters get together and talk about whom to invite to fill the space. Yurters must pay monthly rent for the land, buy or build a yurt, and be willing to split and pay monthly utility bills. (The yurt park gets one utility bill, which covers the bathhouse and its common spaces.) And they have to get along with their neighbors.

The “getting along” has meant different things to different people. When the Dalebouts began the park, they were looking for a simple way to live. As more people moved in, some embraced the idea of a community, a more close-knit group than just people living in similar houses. But others wanted to live more independently. In 1984, tensions mounted between these groups. Ann Kreilkamp, who now lives in a traditional house in Indiana, remembers: “There was polarity in the yurt park, which is so fuc!#%g human. Everybody had their issues. We were a bunch of anarchists trying to get along.”

Dalebout says, “The more people who started living there, the structure of how to organize the growing community would undergo shifts and changes in leadership, and how different people thought the structure of the group should be run.” Generally, one or two people would collect rent and serve as a liaison to the Kents. As more people joined, there were more community meetings and more questions as to how to manage the land and community. “Some wanted to keep things more independent, like me, while others wanted more communal collaboration,” Dalebout says. “There were disagreements, even drama, at certain times, given the personalities of the yurties. But we always muddled through to the other side of some sense of collaborative cohesion.”

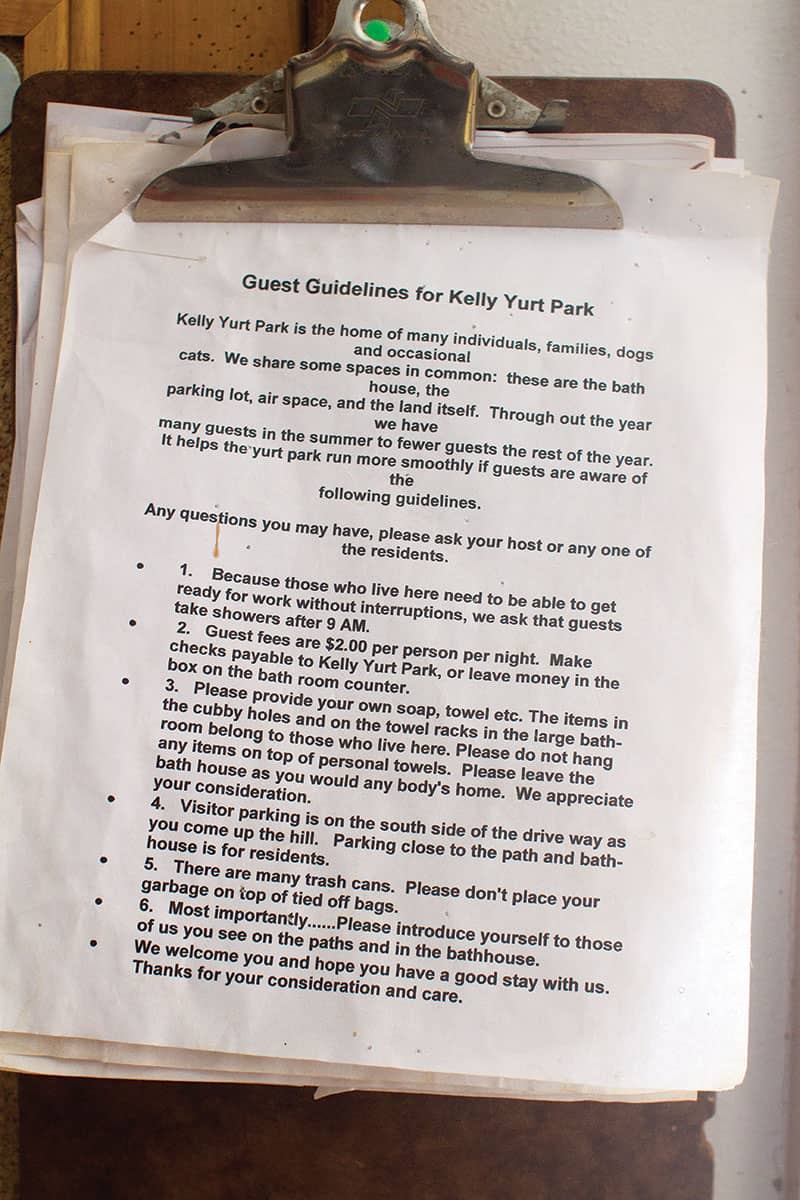

That collaborative cohesion continues today. A sign in the bathhouse asks people to register guests and charges two dollars per day for a guest fee. Residents agreed that parents are exempt from guest fees. FedEx and UPS deliver packages inside the bathhouse door.

As cozy as any single yurt is, the bathhouse is the undeniable heart of the community. It is a 1,200-square-foot building constructed in 1925. It was built as Kelly’s original elementary school, which was fancy at the time since it was a two-room rather than a single-room schoolhouse. By the time the Kents ran this land as a summer campground, it had been converted from a school to a bathhouse. Today, in addition to a shared bathroom and shower area, it has a full kitchen and a laundry room, which doubles as the library. In the bathroom, men and women share three sinks, showers, and toilets, and every resident has a hook with his or her name—most are occupied by towels—and a cubby for toiletries. The bathhouse is heated with electric baseboard heaters; the water is heated with propane. Before cellphones, the bathhouse was home to the yurt park’s lone phone and a message board. The area is still used for messages, but the phone has been replaced by individual cellphones. Residents take turns cleaning the bathhouse, and one person’s idea of clean is often not someone else’s. People leave laundry in the washer, dishes in the sink, and hair in the shower or sinks … some things are timeless.

LIVING SIMPLY AND with a small footprint the yurters certainly do. But harmony with the land? Some days are more harmonious than others. Every resident has a story of being “up close and personal” with wildlife. Wendell Field, a current resident, remembers sleeping with his head nearly touching a bison’s while the bison slept on the outside of the yurt. He could hear it breathing. “People always ask, ‘Where does your property end?’ ” Field says. “And I say, ‘Yellowstone!’ You either love it or you hate it.”

Owen Popinchalk, another current resident, remembers a renter getting up in the middle of the night to use the bathhouse and walking into the dark rear end of a bison. That yurter moved out a month later. In more recent years, people hear the howl of wolves on most winter nights. Growing up, Popinchalk, now thirty-one, spent summers in the yurt park. “Being a kid, it’s like an extension of playing fort,” he says.

Today, custodians, artists, baristas, and mountain guides live in the yurt park. Some people are seasonal. Some rent out their yurts. Some yurts have gardens or extensive decking. Other yurts have neither.

The setup in all the yurts is similar—after all, there’s only so much you can do with 450-ish square feet. There is a bed, dresser, a kitchen area with food and a small refrigerator, and, perhaps most importantly, a wood-burning stove. (Electric lines are run from a central hub to each individual yurt.)

“We carry our own wood, our own water,” Field says. “People think I’m this extreme type of guy, but no. This is how most of the world lives. People say I’m extreme, and I say, ‘No, you are the crazy ones. You have six sinks.’ Jackson Hole has become incredibly polished and rich, and this is kind of the anchor of it, the last authentic way of living in this valley.”

A lot of the problems affecting the yurts come from the wind, not other weather elements. Popinchalk has seen bent chimney pipes and snowdrifts as high as the side of a yurt. Yurters have had to shovel out their entire homes. Neighbors have shoveled out neighbors; whoever can dig their door out from the snowdrift by hand starts digging out others.

Popinchalk has also seen winters where it’s so cold, if a yurt’s fire isn’t constantly stoked, the inside freezes. His brother, Peter, had bottles of vinegar explode when temperatures got too low. The only things that didn’t explode were those inside the refrigerator, which ended up being the warmest place in Peter’s yurt.

UNDERSTANDABLY, THE SPIRIT of helping neighbors pervades the community. “If someone’s not here and we get a big snowstorm, you go knock the snow off their roof,” Field says. Because woodstoves are a yurt’s only source of heat, if someone is gone all day or is away, other yurters will start a fire for them. It can take twelve hours for a yurt to heat up in winter.

Even though there is a waitlist—unofficial, of course—of people that want to live in a yurt in Kelly, there will never be another yurt park in Teton County. After fielding complaints from Kelly residents worried the yurt park would decrease their property values, the county said no to any more yurts in the late 1980s. The Kelly park was grandfathered in.

“Since we didn’t have that bigger vision of a yurt community, I was surprised every year I went back after I had moved out [in 1988] and saw that it was still going,” Dalebout says. “I am impressed with the longevity, endurance, and evolution of what we started. I honor the Kent family for their courage in always supporting the yurt community. And it’s phenomenal that it has gotten wilder over time. Kelly did not have grizzly bears, bison, and wolves wandering through the yurts in the 1980s. I wish that had been the case—that makes living in one even more fun and interesting.”