Read The

Current Issue

Astoria Hot Springs

By Mark Huffman

WHEN ONE OF Jackson Hole’s favorite attractions closed nearly twenty years ago, they shut off the lights and tore down the buildings. But no one turned off the water. Sixteen miles south of Jackson, the spring that made Astoria Hot Springs possible has been sending its flow into the Snake River without cease, the way it did for thousands of years before the first cold and/or dirty human came by, dipped a toe, and decided that hot, running water was the thing to have. Astoria is coming back—organizers are aiming for 2018—to offer the same steaming bliss, but on a much bigger scale.

It’s safe to surmise that Indians used the Astoria springs before white people arrived. They liked a hot bath as much as anyone, even if it was a bit thick. By 1900, the area just south of where the Hoback River meets the Snake was homesteaded by Johnny Counts, one of the earliest Jackson settlers (some of his original buildings are still in the area). Later on, Million Dollar Cowboy Bar founder Ben Goe and his wife, Hilda, owned the land and made a little cash letting people use the springs. They added a couple of changing rooms and not much else. “It was a big ol’ mudhole,” remembers Sharon Gill, a granddaughter of Robert Porter—who bought the hot springs in the 1960s—and a former manager of Astoria Hot Springs. “People went down there and paid to swim in it. The mud would ooze up between your toes, and it had snakes in it.” Robert Gill, another Porter grandchild and former manager, remembers the same thing: It was “a big hole in the ground where the water would overflow and go back into the river … a big, warm mud puddle.”

“This was a locals’ place, and we want it to be that again.”

– Chris deming, Trust for public land

ROBERT PORTER, THE founder of Jackson Drug and an entrepreneur, rancher, and real estate magnate, owned a ranch across the river from the springs. He looked at the mud puddle and saw potential. When Goe died and his widow was on hard times, Porter bought the land.

Besides being a sharp businessman, Porter may have been an early health nut. Robert Gill says his grandfather was active, “interested in sports, swimming—he loved tennis.” Sharon Gill thinks he must have viewed the hot water, as many have over the centuries, as therapeutic. “It was a health thing,” she says. “I think he thought it was going to be a health spa.”

Porter hired Boots Nelson, then an engineering student at the University of Wyoming, to design the Astoria Hot Springs that people now remember. It was Nelson’s thesis, Robert Gill says. The bridge that lets people cross from the highway side of the river was repurposed. Originally, it was part of the old Wilson Bridge, whose concrete abutments can still be seen upstream of Highway 22 in the Snake River. Porter, though, wasn’t able to see the project through. It was all in motion, but he died in March 1961, and the new Astoria welcomed its first enthusiasts that May.

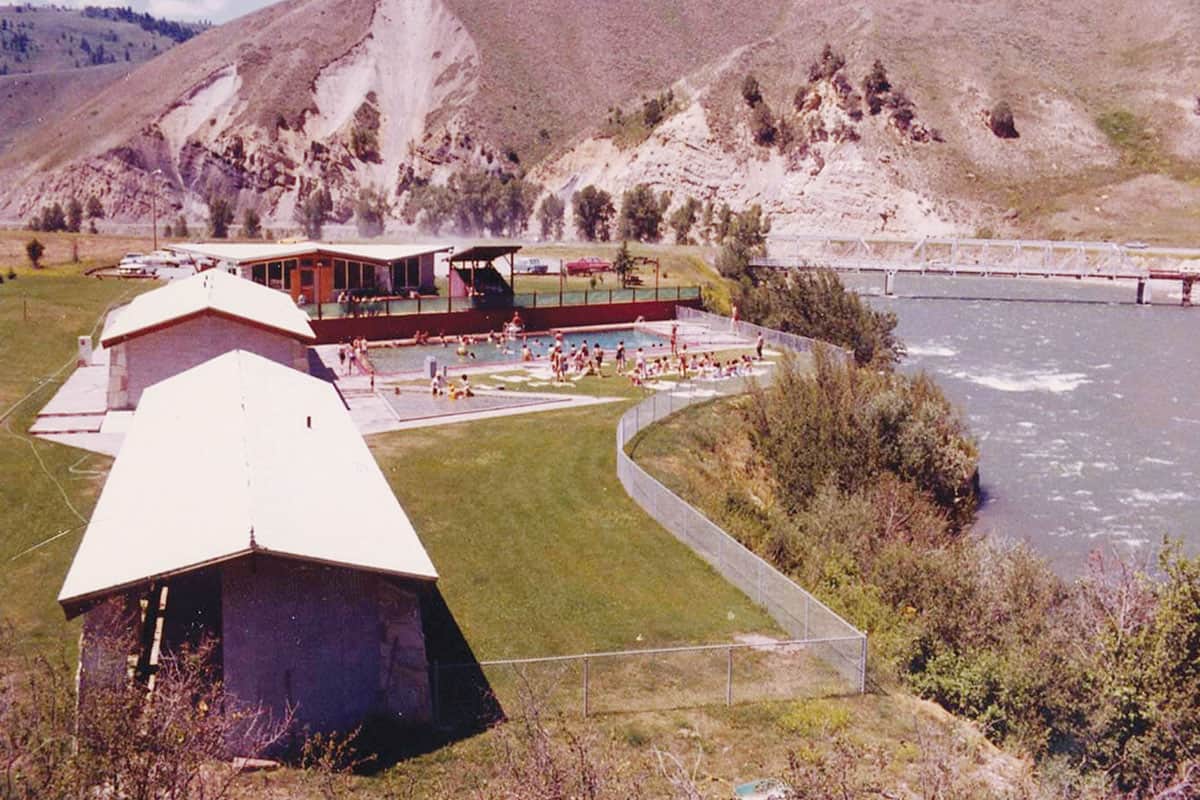

For swimming, there was a 40-by-80-foot pool, from two to eight feet deep. A smaller adjacent pool was for wading and soaking. There were three buildings for locker rooms and a snack bar.

The basic offering, hot mineral water, was free. It came into the pool at about 103 or 104 degrees, Robert Gill says, and cooled in the pool to about 98°F. The flow of the spring was about a million gallons a day, and the pool would fill in eight hours after the twice-weekly draining to flush it out, clean it, and do any repairs. Nelson designed a gravity-fed system; excess water flowed out and into the Snake.

As Porter predicted, people loved it. Astoria grew into something more than a roadside attraction: It was a meeting spot for parties and school events, fundraisers and reunions, a place that became part of the memories of thousands of people. It wasn’t a trip to Disneyland, but maybe that was a big part of why people loved it so much—it was a small-town kind of attraction for a small town.

“I had swim team down there. … I remember going to Girl Scout campouts there, end-of-the-school-year picnics, and birthday parties,” says Paige Byron of the Northern Rockies-Wyoming office of the Trust for Public Land. Chris Deming, the project manager for the Northern Rockies-Wyoming office, which is spearheading the revival of the hot springs, says, “It was the locals’ place to go, to have those memories that shaped generations. It all has to do with being at that hot springs.”

AS POPULAR AS the pool was, it wasn’t a great business. Campers and RVs kept it afloat. Ralph Gill, who married into the Porter family and took over when Porter died, built thirty-two spaces with full hookups and many other camping spots along the river. “It ran a lot of years without making any money,” Ralph Gill’s sister, Sharon Gill, says of the pool. Keeping prices down and being open only in the summer meant that “it was the campground that made money.”

Eventually the camping income wasn’t enough. Various members of the Gill and Porter families owned shares in Astoria. When the time came in the late 1990s for a big repair—“that mineral water is very hard on things,” Robert Gill says—the will and the finances didn’t add up. “Selling it was the most difficult decision we ever made, at least it was for me. But it was deteriorating, and we were putting pretty much everything we got out of it back into it.”

Astoria Hot Springs closed in 1998. Dick Edgcomb, a Jackson developer who was planning the Canyon Club (now the Snake River Sporting Club), bought the land.

Edgcomb’s view of Astoria didn’t include a roadside hot springs and people camping in tents and RVs: The Canyon Club would have a forty-unit lodge of more than 100,000 square feet with twenty-three homes built around it. It was one of those deals that started and stopped because of financing and fights with the government. Edgcomb was broke by 2005. The land changed hands several times before its current owners stepped in. They completed the clubhouse in 2009 and got the golf course back in shape after it had sat unused for several years. They also said they were willing to talk about a new plan for the hot springs. “I’ll be glad to see it come back; people are going to love it down there,” says Ralph Gill’s daughter, Liz Gill Lockhart. “It’s a case of what’s old is cool again.”

Heating Up Again

IN LESS THAN forty years, Astoria went from a mudhole to a roadside hot springs pool to a bulldozed piece of land that was going to become a luxury hotel surrounded by second homes. Thank shaky finances and the Great Recession for its return as a hot springs pool that will be open to the public.

When Northlight Financial, the eventual buyer of one hundred acres that will be redeveloped, purchased the land, it intended to go ahead with commercial and residential development. But a proposal by the Trust for Public Land changed that. Instead, development approved for the site has been cut, and the remainder transferred down the road to Snake River Sporting Club.

The trust recently began campaigning to raise $5 million to buy the one hundred acres and pay the cost of bringing Astoria back. The trust aims by 2018 to renovate the old Johnny Counts cabin and build a new headquarters, locker room building, and several pools. Included will be a 1,700-square-foot “leisure pool,” about the same size as the old Astoria pool but shaped like a pond rather than a rectangle. Water will be between 94 and 98 degrees. Kids get a pool of their own; it will be slightly cooler than the leisure pool. Three or four soaking pools will be in the 100-degree range. They’ll be surrounded by decks and offer a more intimate experience. There will be lawn and picnic space. Though the old Astoria was open just in summer, the new operation will run year-round.

The new pools and associated facilities will be on five acres next to the Snake River at the old Astoria site. Along the river just south of the bridge will be a park with fishing ponds and additional parking spaces. Much of the rest of the parcel will remain wild. The entire area will be criss-crossed by three miles of trails.

The Trust for Public Land, an offshoot of the Nature Conservancy, focuses on “conserving land for people” rather than maintaining strictly natural conditions, says Chris Deming, the group’s leader in Jackson. Astoria is a perfect project for the group, he says, because of the connection of place and people. “This was a locals’ place, and we want it to be that again,” Deming says. “We want it to be a wonderful place for the next fifty years.”

To see plans for the redevelopment and to donate, go to astoriahotspringspark.com.