Read The

Current Issue

Cowboy Science

A nonprofit lab in Jackson is closing in on treatments for ALS and Alzheimer’s.

By Dina Mishev

Ethnobotanist Dr. Paul Cox, one of Brain Chemistry Labs’ founders, grew up spending time in Jackson Hole. He says locating the nonprofit’s lab in Jackson has benefits including the generosity of local donors. Donors who contributed $150,000 to the Phase II trial led by a consortium scientist got a “Serine Dipity” sweatshirt. “Serine Dipity” is a play on the name of the amino acid BCL research shows might be a treatment for ALS and Alzheimer’s. Photo by Ryan Dorgan

“Laws of physics and chemistry hold true here in Wyoming just as they would in Berkeley, California, or Sydney, Australia.” So says Paul Cox, an ethnobotanist with a PhD from Harvard, to explain why Jackson Hole is Brain Chemistry Labs’ (BCL) world headquarters-—despite the valley being in an isolated corner of the least populated state in the U.S. and hours from any academic research center or pharmaceutical lab. Dr. Sandra Banack, whom Cox recruited to BCL from the University of California, Berkeley, where she had lifetime tenure says, “I think the question is ‘Why not Jackson?’”

BCL’s work started while Cox was based in Kauai and director of the National Tropical Botanical Garden, a collection of five preserves in Florida and Hawaii. BCL works with human brain tissue and, Cox says, “It got very difficult to carry human brains through TSA. “I was carrying [containers] with smoke and stuff coming out of them from dry ice. It was the definition of suspicious. We realized we needed to move to the mainland.”

“If Jackson was going to be renamed right now, it should be ‘Humility.’ This town has been amazing in its support of finding treatments for diseases that pharmaceutical companies have given up on.”

—Dr. Paul Cox, Brain Chemistry Labs founder

BCL is not only unique for being a top-level research lab in a state lacking anything like it, but also for the research it does and the way it does it. BCL’s research and ongoing FDA-approved phase II clinical trials show progress on treatments for ALS (Lou Gherig’s disease) and early-stage Alzheimer’s. Neither of these diseases currently has treatments that provide anything but limited, temporary relief. And, unlike the majority of other pharmaceutical labs, BCL is a nonprofit; board members do not expect any commercial return. Its annual budget is about $2.5 million and there are only four PhDs on staff: Cox, Banack, James Metcalf, and Rachael Dunlop. Another 50 scientists who are experts in 28 different disciplines, from neurology to physics, chemistry, and oceanography, are part of an extended BCL consortium. They share their unpublished research with the goal of developing treatments and cures for brain diseases based on unique theories Cox developed while studying the Chamorro people of Guam (see sidebar). Consortium scientists are based in 12 countries and get together once a year, usually in Jackson Hole. “This isn’t a difficult place to get people to come to,” Cox says.

Jackson hole was on Cox’s radar as a potential location for BCL because he spent time in the valley when he was young: his dad was a seasonal ranger in Grand Teton National Park and his mother did research at the Jackson National Fish Hatchery. “I always loved it here,” Cox says. “And it’s turned out to be a great decision for us, for so many reasons.” Cox tells a story about bargaining for a piece of machinery that was tens of thousands of dollars beyond the lab’s budget. “I pointed out to [the company] that they would have to travel to calibrate the machine five times a year,” he says. “I asked them if they skied, snowboarded, rafted, hiked, or watched birds. There was silence for about 90 seconds then I heard, ‘Sold.’”

When BCL ran out of immersion oil for its microscope, St. John’s Health gave them some. The biggest benefit might actually be what some would think to be a drawback: the state’s isolation. But, “The isolation gives us time and focus to concentrate on what we’re doing,” Banack says. “And when we want to interact, it is a heartbeat away. There are no interruptions unless we want them. Coming from a university environment, you spend so much time sitting in meetings and wasting time; here all of our time is spent doing research and there’s not the dogma and red tape. In Jackson we have the freedom to follow the science; it’s kind of a cowboy approach.”

The wealth in Jackson has also benefitted the lab, which, as a nonprofit, has the mantra, “for patients, not profits,” Cox says. Most of the owners of what might be the world’s most expensive sweatshirt live in Jackson Hole. Emblazoned with “Serine Dipity,” a play on the name of the amino acid L-serine (see sidebar), which BCL research shows might be a treatment for ALS and Alzheimer’s, these sweatshirts were given to individuals who donated $150,000 (or more) to one of BCL’s phase II trials. this raised a total of about $2 million.

“I can’t think of any other time in history where a group of citizens decided they would fund their own trial,” Cox says. “This is where Jackson really shines. Every year we max out at Old Bill’s [Fun Run for Charities]—it’s amazing. We have some really generous people here who are interested in the public good and really want to help take on these diseases that the pharmaceutical companies have given up on. It’s a long shot, but we’re taking it.” JH

From Guam to Jackson

Brain Chemistry Labs has its roots in Guam. After World War II, the Pacific island’s Chamorro people were up to 100 times more likely as people elsewhere in the world to develop symptoms characteristic of neurodegenerative diseases like ALS, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s: slurred speech, facial paralysis, loss of motor skills, immobility, and dementia. Locals called this lytico-bodig (from the Spanish paralytico, meaning weakness).

Scientists from around the world had studied the Chamorro cluster, ruled out a genetic cause, and developed theories about environmental triggers including the seeds of the cycad tree, which locals ground into flour to make tortillas. Paul Cox and his colleagues discovered that cyanobacteria in the roots of Guam’s cycad tree produce beta-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA), a toxin. In high quantities—much, much higher than any Chamorro could get from eating tortillas—BMAA was known to kill nerve cells and induce symptoms of lytico-bodig when fed to monkeys.

Dr. Cox, the late neurologist Oliver Sacks (known for his books including Awakenings and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat), biologist Sandra Banack, and Canadian chemist Susan Murch came up with a novel and compelling theory: One of the most important foods in the Chamorros’ diet, flying fox stew, included biomagnified levels of BMAA. Every night, Guam’s flying foxes ate up to one pound of BMAA-rich cycad seeds. A foundation of this hypothesis was that as the flying fox population on Guam declined and Chamorros ate fewer of them, the incidence of lytico-bodig also declined. Due to commercial hunting, the bats were virtually extinct by 1970. Since then, lytico-bodig declined into relative obscurity and it is difficult to find anyone born after 1960 with the disease.

Cox worked with Banack and Murch to confirm the theory that the Chamorros had been poisoning themselves. They found massive levels of BMAA in specimens of the bat preserved in museum collections around the world. Along the way they made an additional discovery: lytico-bodig seemed to be related to brain diseases throughout the world. They didn’t just find BMAA in the brain tissue of Chamorros who had died of the diseases, but also in the brains of Canadian Alzheimer’s victims who did not eat flying fox, but could have been exposed in other ways to the cyanobacteria that produces the toxin. Cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green algae, is nearly ubiquitous on Earth—from the cycad trees of Guam to oceans, deserts, and even Yellowstone’s hot pools. “The road to Brain Chemistry Labs starts in Guam,” Cox says.

L-Serine

The Brain Chemistry Labs consortium found that BMAA substituted for L-serine, a dietary amino acid that, along with 19 other amino acids, make up human proteins. The L-serine molecules are often the site where proteins are charged so they can be properly folded. Misfolded proteins in the brain characterize diseases including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. Our body produces L-serine; it is also abundant in soy products, sweet potatoes, eggs, some edible seaweed, and even bacon and other meats. You can buy L-serine supplements and powders on Amazon.

In February, a study published in Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology authored by members of the Brain Chemistry Labs consortium showed that L-serine supplementation successfully reduced ALS-like changes in an animal model of ALS. At Dartmouth Medical School, consortium member Dr. Elijah Stommel, a professor of neurology, is conducting a Phase II trial of L-serine in 50 ALS patients. Consortium member Dr. Aleksandra Stark is conducting a Phase IIa study of L-serine in early-stage Alzheimer’s patients at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center.

While this research provides valuable insights, at this time the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved L-serine for the prevention, treatment, or mitigation of any disease. It is recommended that anyone considering supplementing their diet with L-serine consult with their physician.

Toxic Puzzle

Paul Cox, Brain Chemistry Labs (BCL), and cyanobacteria are the stars of the award-winning 2017 documentary Toxic Puzzle, which Harrison Ford narrates and was made over four years by Swedish biologist and founding director of Scandinature Film, Bo Landin. Toxic Puzzle follows Cox and BCL collaborators around the world as they collect cyanobacteria, learn more about the toxic substances it produces, and discover enough of a link between it and ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease), Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s that, after watching it, we didn’t want to be anywhere near cyanobacteria blooms. Available for streaming on iTunes and Amazon, Toxicpuzzle.com

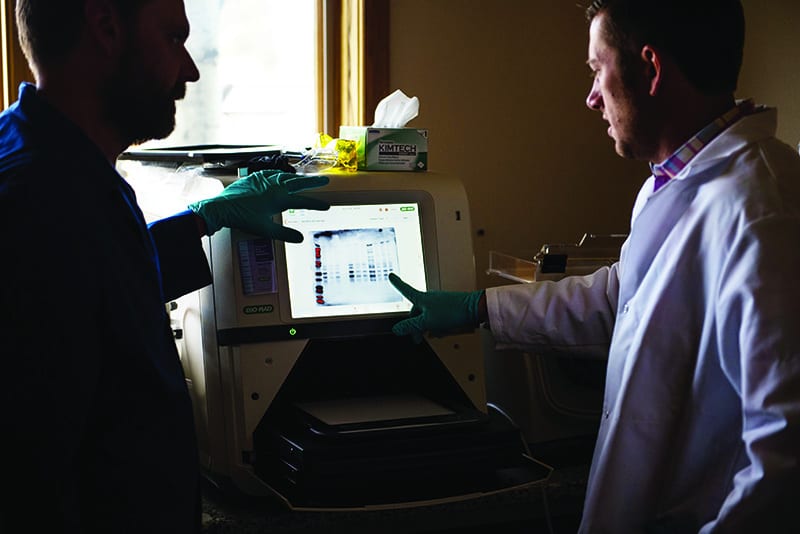

Dr. James Metcalf (left) and a former Brain Chemistry Labs researcher look at a plate that allows them to measure changes in the genetic material of patients who have neurodegenerative disease. They do this to understand what causes the disease and how genes might be contributing. Photo by Taylor Glenn

A beaker full of cyanobacteria. The majority of the research Brain Chemistry Labs does is with cyanobacteria, aka blue-green algae, and a toxin found in it, BMAA. BCL research has found BMAA in the brains of people who have died of Alzheimer’s and ALS.Photo by Taylor Glenn

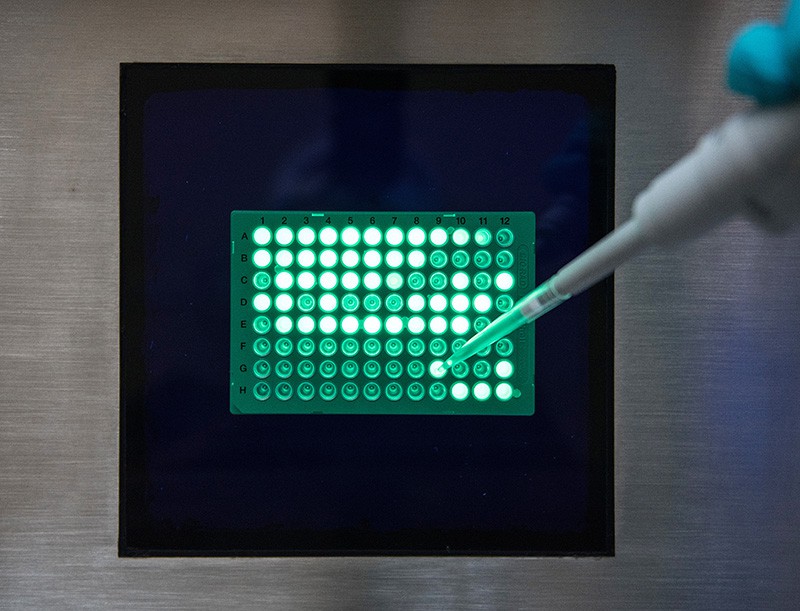

BCL scientists study changes in proteins in patients’ samples, which can be seen here. BCL’s Dr. Rachael Dunlop says, “Proteins are the product of genes and if they don’t function properly, they can cause or contribute to disease. If we know which proteins are affected in patients, we can design targeted therapies.” Photo by Taylor Glenn