Read The

Current Issue

Crown Jewels at the End of their Golden Age?

As the National Park Service turns one hundred, the examples set by—and the problems seen by—Yellowstone and Grand Teton parks are more important than ever.

By Todd Wilkinson

WALLACE STEGNER, THE late godfather of contemporary western literature, famously declared national parks the best idea America ever had.

With high-profile help from noted filmmaker Ken Burns and historian Dayton Duncan (who together produced the six-episode 2009 documentary aired on PBS, The National Parks: America’s Best Idea)—and passionate boosters like Jackson Hole author and poet Terry Tempest Williams—our national parks have certainly been popularized as sacred shrines woven deep into the fabric of our country. They’re held up as birthrights that come with citizenship. As places to escape the cacophony of urban civilization. As touchstones of history. As venues where nature still wields primacy and authority. And today, as attractions that make the cash registers in gateway communities sing with the sound of commerce. In 2014, the most recent year for which statistics are available, nearly 292 million visits were notched to all federal park units. More than 8 million of those were recorded in Grand Teton and Yellowstone national parks, the two parks closest to Jackson Hole and the two preserves that give this valley much of its identity. In 2015, the attendance figure was even higher, with record numbers passing through the entrance stations of both parks.

When I ask author David Quammen if Stegner’s adage resonates with him, he delivers a surprising answer: “National parks as America’s best idea? No, I think our greatest contribution to the world has been our model of modern democracy,” Quammen says. “But parks are a brilliant concept that becomes more important with age. What they are and the role they play continues to evolve. I think, in that sense, parks serve as mirrors, reflecting what kind of country we aspire to be.”

On August 25, 2016, the National Park Service (NPS), the government agency that manages the parks, turns a century old. While it is the centenary of the NPS that is being celebrated this year, Yellowstone and Grand Teton parks figure at the center of an unprecedented edition of National Geographic magazine. The April 2016 issue focuses entirely on the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, which has Yellowstone and Grand Teton at its geographical heart. Quammen, who lives in Bozeman, Montana, penned the whole issue—the first time that honor has been bestowed upon a single writer in the legendary yellow magazine’s 127-year history.

ALL TOLD, THE NPS encompasses 408 “units” in the form of parks, monuments, battlefields, recreation areas, the homes of famous Americans, and other historical or ecological areas significant at a national level. Of course it is the parks—fifty-nine in twenty-seven states—that are the service’s pride, and only a handful of these are considered true crown jewels: Yellowstone, which was the country’s first national park and actually preceded the NPS by forty-four years, along with Yosemite, Great Smoky Mountains, and Grand Teton, among a select few others.

With a 2015 budget of $3.65 billion, the NPS has 22,000 employees, from iconic rangers and scientists to historians, law enforcement, and seasonal trail crews. Rangers today manage bear jams in Yellowstone and Grand Teton, rescue injured climbers from peril in the Tetons, and host campfire chats. In 1963, they flanked Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. when he delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., with the Lincoln Memorial at his back.

In their documentary, following an exhaustive coast-to-coast exploration trying to put their finger on the essence of national parks, Burns and Duncan said that parks “are more than a collection of rocks and trees and inspiration scenes from nature. They embody something less tangible yet equally enduring—an idea, born in the United States nearly a century after its creation, as uniquely American as the Declaration of Independence and just as radical.”

Like the Declaration of Independence, which promulgated the founding of this country, the Park Service, which is administered by the U.S. Department of the Interior, traces its origin to a document, the 1916 Organic Act. The act established public enjoyment and resource protection as its principal objectives.

In public opinion polls through the years, the National Park Service has been consistently regarded as one of the most beloved agencies in the federal government, says former Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt. So fond are Americans that 221,000 volunteer to work in parks nationwide every year. Yet, in recent years, its budget has not kept pace with the growing demands of keeping parks running. Today, the NPS has a maintenance backlog of $11.5 billion. Parks, despite increased visitation, are expected to deliver far more on much less. Besides carrying out the usual duties of tourism, parks are laboratories for science, and the age of heightened ecological consciousness has created more demands to have management informed by research.

YELLOWSTONE, BORN BY an act of Congress in 1872, is not only the first national park in the United States but also in the world. No one suspected this at the time, but it became a template. Denis Galvan, the longtime NPS policy chief, who is now retired, notes that America’s park system became the model emulated globally.

The origin tale of Yellowstone is packaged like this: once upon a time a group of farsighted white-guy conservationists sat around a campfire and conceived of the national park ideal. The reality is that Yellowstone came into being as a ruse—carve a protected area out of the rapidly dwindling frontier and Easterners will want to visit it, buying tickets on the newly established transcontinental rail line.

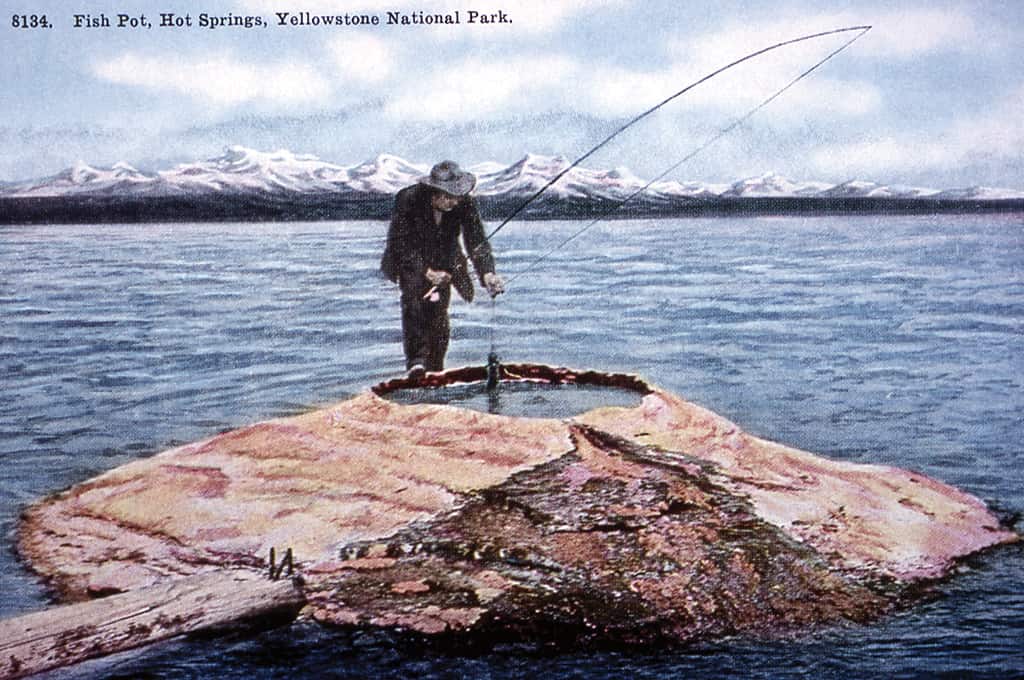

These early Yellowstone visitors didn’t come because they were green-minded but for refined adventure. Members of the American upper crust, they dined on white tablecloths in rustic luxury lodges at night and, by day, tramped around the park’s geothermal features, often trampling them and even bathing and washing their clothes in them. They hauled unsustainable numbers of trout out of lakes and streams, threw out table scraps to lure in bears for viewing, and chipped off chunks of travertine to bring home as souvenirs. In the park’s earliest days, its elk were hunted and killed to feed guests and rangers. Only later, and incrementally over decades as the toll on resources rose, did Yellowstone’s—and the national parks’ in general—purpose become protecting its natural wonders, ecosystems, and landscapes.

But even today there are contradictions. Yellowstone has the greatest migrations of megafauna in the Lower 48, but the state of Montana has killed over eight thousand Yellowstone bison since the 1980s. Bison of course don’t recognize invisible boundaries and, in winter, while looking for forage, often wander out of the park’s safe confines. Bison carry the disease brucellosis, which causes females to abort their firstborn, and it is feared they will transmit the disease to private cattle herds grazing nearby, even though there has never been a documented case of such a transmission happening. Cattle herds in Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho have indeed been infected, but all cases involving wildlife have been traced to brucellosis-carrying wild elk.

Yellowstone is not alone in its incongruities. Sage grouse and hikers in Grand Teton National Park (GTNP) both are bothered by jets landing and taking off from the Jackson Hole Airport, the only airport in the country inside a national park. In the same park, for ten and a half months of each year, it is illegal to “invade the space” of wildlife (the distances vary for different species) or to otherwise harass them. And yet, every autumn, GTNP allows hunters to kill a select number of elk within its borders.

Wildlife officials say the hunt is necessary to reduce the number of wapiti, but immediately adjacent to the park, in the National Elk Refuge, thousands of elk are artificially fed. The park and elk refuge are at cross-purposes. Feeding elk also is known to increase the percentage of them carrying brucellosis and it leaves herds vulnerable to a new, looming threat: chronic wasting disease.

Although there is no shortage of controversies, common sense often prevails. For years, rising numbers of snowmobiles in Yellowstone had reached a crisis point with air and noise pollution. It got so bad that rangers working the entrance station at West Yellowstone, Montana—the self-proclaimed “snowmobile capital of the world”—wore gas masks to protect their lungs from pollution. However, recent agreements have reduced the number of snowmobiles allowed to enter the park, given way to new generations of cleaner-running vehicles, and resulted in more tourists being ferried into Old Faithful during the winter via quieter snowcoaches.

In his landmark book, Preserving Nature In the National Parks: A History, retired NPS historian Richard West Sellars addresses this sometimes-schizophrenic approach to park management—accommodating the desires of people and also claiming to protect resources through decision-making informed by science. When Sellars’ book was published in 1997 he was skeptical that the Park Service could successfully step up to and fend off meddling by politicians and business interests that put commerce before environmental protection. That debate still rages and is as complex and complicated as ever.

MANY PEOPLE IN Wyoming vigorously resisted efforts to have the grizzly bear receive federal protection under the Endangered Species Act and for wolf restoration in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Both were successful, and in their wake today is a thriving nonconsumptive wildlife safari industry. In addition, claims that bears and wolves would cause significant damage to big game herds and livestock have proved to be exaggerated.

Today, the two parks anchor an annual $1 billion nature-tourism economy, from wolf- and grizzly-watchers to wildlife photographers, backpackers, cyclists, hikers, anglers, and those for whom a trip to Yellowstone is still considered an all-American vacation. After agriculture and energy development/mining, the northwest corner of Wyoming, defined by protected public landscapes, is the third major pillar of the state’s economy.

This fall, during an interview at his office—constructed long ago by the U.S. Cavalry before there were cars—Yellowstone superintendent Dan Wenk was reeling from the busiest tourist season ever recorded in the national park. “These days are different from the era when families would pile into a station wagon and trek cross-country to get here on vacation,” Wenk says. “But the notion of Yellowstone being a necessary pilgrimage still lives large for people in this country.”

Still, Jackson Hole resident Joan Anzelmo, who spent decades working for the NPS, holding a number of senior leadership positions, is worried that many Americans take parks for granted. “If we were depending on today’s Congress to establish national parks, there would be no Yellowstone, no Grand Canyon, no Yosemite, and no uniquely American system of national parks that are the exemplar of the world,” she says.

Anzelmo shares a quote from the journals of John Muir, who penned this observation in 1898 following one of his two visits to Yellowstone: “Climb the mountains and get their good tidings. Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds will blow their own freshness into you, and the storms their energy, while cares will drop away from you like the leaves of autumn.”

At the time of Muir’s visit, fewer than twelve thousand people came to Yellowstone each year. In 2015, for the first time in its 143-year history, Yellowstone had over four million visitors. By the end of September 2015, both Yellowstone and GTNP had each had more visitors than in the entirety of 2014.

The NPS has an $11.5 billion backlog, with $1 billion of that accrued in Yellowstone alone; much of this involves the park’s three-hundred-plus miles of crumbling highways. Wenk says that during peak summer visitation, Yellowstone surpasses its carrying capacity. The park is being visited to death. If visitation continues to rise, it is inevitable that the quality of the visitor experience will be diminished.

So what will Yellowstone do?

I remember a conversation I had with late U.S. Senator Malcolm Wallop, of Wyoming, in the early 1990s when he presciently said the only antidote was getting people untethered from their cars. Wallop suggested looking at the feasibility of a Disney World-like monorail in Yellowstone. It was roundly rejected as too costly and impractical. The irony is that had it been built a quarter-century ago, it would have likely cost less than the park’s current maintenance backlog.

MIKE FINLEY SPENT thirty-two years with the Park Service, working his way up to park superintendent, first of Everglades, then Yosemite, and finally Yellowstone. He points to something that he calls a “holy oath”—it’s the sacred trust that all elected officials are bound to uphold on behalf of the American people, and it’s to abide by the law. The 1916 Organic Act is clear in stating the duty of superintendents is to make management decisions that leave parks unimpaired for future generations, Finley says.

Etched into the Roosevelt Arch at the Northern Entrance to Yellowstone are the words, “For the Benefit and Enjoyment of the People.” Finley notes that in the dual purpose of entertaining people and maintaining the line on resource protection, courts have sided with the latter.

In one of the most colorful quotes I’ve ever heard from a Yellowstone superintendent during my thirty years of writing about national parks, after keeping a ban on paddling the park’s rivers in place because of concerns for wildlife, Bob Barbee (superintendent from 1983-94) told me: “The smooth marble floor of the Sistine Chapel or the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., would frankly be great for skateboarding and roller blading—terrific places to have fun on wheels and get a good workout in—but we don’t allow it. Why? Because it comes down to self-restraint and having respect for special places.” (Side note: although Barbee upheld the paddling ban in the early 1990s and it was kept intact by his successors, the prohibition is being challenged today by a Jackson Hole-based group of packrafters who has enlisted the help of U.S. Representative Cynthia Lummis, of Wyoming. It reminds me of the words of the late American conservationist David Brower who said, “No conservation victories are ever permanent. Some battles are destined to be fought again and again as each generation must learn anew the value of conservation.”)

DESPITE THE CHALLENGES, Wenk points to the catalyst that causes him to rise enthusiastically out of bed every morning: “People love this place. They dream of coming here. When they arrive and they see a bear or a moose or elk or they stroll through the boardwalks of the geyser basins, they experience the magic, it becomes part of their family history, and they remember it for the rest of their lives.”

The power of national parks transcends biology. Every year, visitors send the ashes of loved ones spiraling into the chasm of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. Or they climb the Grand Teton and scatter them from the summit. Marriage proposals are made at scenic overlooks, and the elderly and those seeking to have their last wishes fulfilled come to parks to gaze upon places or animals that matter to them.

Before Dave Hallac left Yellowstone as its chief scientist last year and became superintendent of Cape Hatteras National Seashore, he and I walked along a tiny creek discussing threats to the park, many of which are off the radar of its millions of visitors.

“The inspiring thing to me is that this might be Yellowstone’s Golden Age. At no point in the last one hundred years has this place—with the restoration of wolves and recovery of grizzly bears—felt wilder,” he said. “And yet, if you examine all of the scientific evidence and look at the trendlines of human visitation, development, exotic organisms taking hold, and climate change, it could all unravel. We could lose it and we’re going to lose it faster if we don’t come to terms with its limitations.”

In Searching for Yellowstone, Paul Schullery penned what I believe is arguably the best philosophical reflection about the importance not only of Yellowstone but all of our national parks. Yellowstone, he says, is like the Shangri-La of Lost Horizon, James Hilton’s classic novel of a secret Himalayan paradise. “Its residents and visitors knew that Shangri-La was precious, and they knew it contained important treasures, especially in the lessons it held for the rest of the world. But they also knew that it alone could not serve the world’s many needs.”

Schullery considers Yellowstone and Grand Teton parks an interconnected lifeboat, not only physically protecting wildlife and natural wonders, but also serving as a beacon that proves humans are capable of exercising self-restraint in refraining from destroying the natural places they profess to love.

But with rising human population, the impacts of climate change, and new user groups pushing for access, he’s concerned about the park buckling under the new, unprecedented pressures.

“For all our increased awareness of the vulnerability of this particular lifeboat, we do not seem to have figured out how to prevent it from going down,” Schullery says. “In our attempts to justify our positions in the debates over Yellowstone’s management, we invoke the needs of future generations, because we see our care of this place as a great trust. We are saving these things for them, and they’ll never forgive us if we mess it up.”