Read The

Current Issue

Cutthroat Paradise: Jackson Hole

The Upper Snake watershed is the last, best, and largest watershed dominated by cutthroat trout remaining in the West, but the continuance of this status isn’t a given.

By Mike Koshmrl

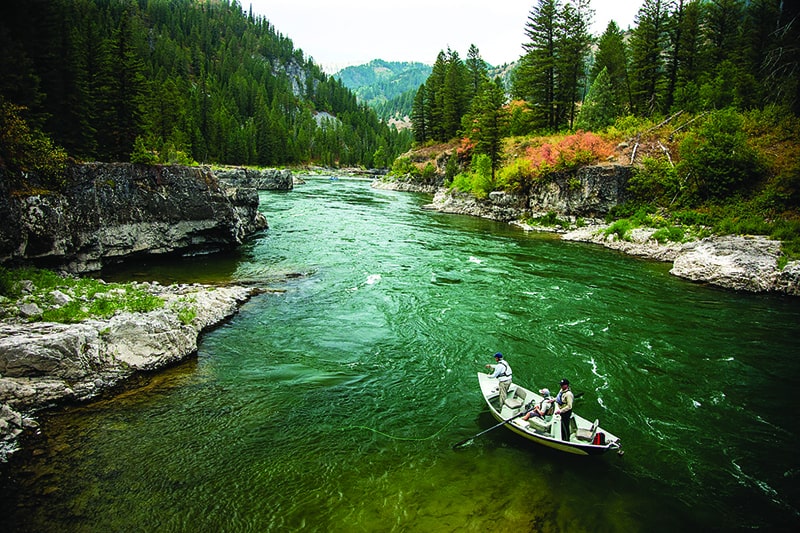

The portion of the Snake River that winds through Jackson Hole is one of the few areas in which the river’s native cutthroat are the dominant trout. The Snake’s native cutthroat are fine-spotted cutthroat, a subspecies genetically identical to the Yellowstone cutthroat. Photo by Bradly J. Boner

OVER THREE COLD fall days last year, Rob Gipson’s Wyoming Game and Fish Department crew went through the motions of sampling the trout that swim the Snake River. The river stretch sampled oscillates annually—this time it was Moose to Wilson—but it’s a routine operation that relies on electricity. Some 250 volts of power and 2 amps of pulsed direct current course into the sloshing Snake via electric nodes that dangle from a raft. These shock and immobilize fish that are then netted, measured, weighed, and released to live another day.

The tally from the late October three-day outing, exactly 1,149 fish, was somewhat ordinary. Also commonplace for the Snake River: 99 percent of the salmonids sampled had fine spots and a characteristic blood-orange colored slash under their gills. They were cutthroat, the native trout that evolved over eons to be here. What’s extraordinary is that these cutthroat trout are still here. “That intact native fish community we have is incredibly unique,” says Diana Miller, one of Gipson’s fisheries biologist colleagues. “And we have that with very few nonnative fish in general. That’s very unique. Most places just can’t say that their native fish are the dominant fish, both game fish and otherwise.”

The watershed’s still-thriving native cutthroat are the dominant trout from the headwaters of the Snake at Two Ocean Plateau all the way to Palisades Reservoir—and in tributaries reaching in every direction. They are an anachronism in a world where cutthroat trout as a species are reeling. There were 14 unique subspecies of the trout that evolved in western North American waters. Two are extinct. None is faring all that well. The local subspecies in the Snake watershed is the Yellowstone cutthroat. (Confusingly, the state of Wyoming recognizes Snake River fine-spotted cutthroat as a distinct species, although genetically it is identical to Yellowstone cutthroat.)

There’s a complex web of impacts that threaten to worsen and have already driven down cutthroat populations and reduced their occupied range. Competition and hybridization from exotic, introduced salmonids—especially brook, brown, and rainbow trout—are big culprits. Agriculture has pulled water out of cutthroat watersheds, and dams have diced them up. Meanwhile, climate change is cooking the cutthroat habitat and will continue to warm the cold-water streams salmonids depend on: One 2011 Trout Unlimited study predicted that using a “middle of the road” greenhouse gas scenario, cutthroat would lose 58 percent of their remaining habitat by 2080.

Look at a map of historic cutthroat distribution versus where they dwell today, and the single largest remaining blob of still-occupied habitat is in the southern Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. It’s the sprawling web of cold-water streams and rivers that drain into the Snake River, which bisects the heart of Jackson Hole. The interconnectedness and dearth of dams and diversions is part of what keeps the Snake a cutthroat stronghold, U.S. Geological Survey research fisheries biologist Robert Al-Chokhachy says. “One of the things that makes the Snake so impressive is that you have a large river that is connected to tributaries,” he says. “That allows fish to have so many life histories. There are spring creeks that have stable hydrographs and stable thermal regimes, all the way to larger rivers like the Hoback and the Buffalo Fork. And then you have small tributaries, like Ditch Creek. That diversity is what makes the Snake so special.”

“You can take an expert, well-traveled trout fisherman and put him on a cutthroat river, and he’s going to be a step or two off. That’s what I appreciate about the cutthroat.”

—Paul Bruun, former fly-fishing guide who has fished the Snake River and its tributaries for more than 50 years.

There are only two cutthroat-dominated river systems that come anywhere close to the Snake in scope, Al-Chokhachy says: the South Fork of the Flathead River in northwest Montana and the upper Yellowstone River above Yellowstone Lake. “In terms of freshwater trout in the Intermountain West, those are the three river systems that have a semblance to what they were,” Al-Chokhachy says. “All three have an abundance of public land. That’s probably what makes them so special.” But both the Flathead and Upper Yellowstone are backcountry environments, whereas the Snake flows through a community that harbors nearly 25,000 residents—and twice as many tourists and seasonal residents during the busiest times of year. Dozens of fishing guides make their living in Jackson Hole, and they can boast of their unparalleled hometown cutthroat fishery.

While it’s a unique selling point, it’s not always intuitive to anglers who aren’t educated about native trout conservation and are accustomed to catching rainbow, brown, and brook trout that have been introduced into and invaded so much of the West. “I would say 85 percent of our clients have no idea coming in,” Jackson Hole Angler owner and founder Dave Ellerstein says. “But we work hard to educate them about how special the cutthroat fishery is. That’s part of our job, so they have an appreciation for it.”

CONTINUITY OF THE past and present is not assured. Almost everywhere else—including watersheds just a hydrological divide away from Jackson Hole—cutthroat are spotty in distribution, relegated to the highest, most remote reaches of watersheds. Or they’ve been extirpated. Leslie Steen, the one-woman show running Trout Unlimited’s Snake River Headwaters Initiative, says you don’t have to go far to see the alternative: just take a drive over Togwotee or Teton Pass, or cruise past the Palisades Dam or over the Hoback Rim. “We are surrounded by highly compromised, non-intact watersheds,” Steen says. “They’re great fisheries, but they’re not like what we have [in Jackson Hole]. As time goes by and the climate warms, this might be one of the last best places for cutthroat, if we can hang onto it.”

It’s at the heart of Steen’s job to ensure they hang on. In late November, she stood on the banks of lower Spread Creek, at the site of a where a 13-foot-tall, 125-foot-long concrete and metal diversion dam once severed the creek system from the Snake River. The barrier came down in 2010, but almost a decade later another problem had emerged: cutthroat trout, by the hundreds, were becoming entrained in the still-functioning diversion ditches, which sends Spread Creek water toward the Elk Ranch Flats area, grazed by Pinto Ranch cattle. “Fish can make it up [Spread Creek] now,” Steen says. “We’re just going to make it better.”

Steen is trying to raise around $1.5 million to add fish screen and keep the irrigation channels in working order by stabilizing the dynamic creek. Trout Unlimited is driving and/or has a hand in many other projects like this, with the goal of helping out native cutthroat, and they take place all around the watershed. Tributaries of the upper Gros Ventre River severed by relic diversions have been reconnected. The culvert carrying Game Creek under South Highway 89 was swapped out so cutthroat can swim upstream. Floodplains have been restored on tiny Tincup Creek in southeast Idaho, which feeds into the Salt River, which joins the Snake at Palisades Reservoir.

Wyoming Game and Fish has also made it a mission to prioritize cutthroat, though that wasn’t always the case. Up until the 1990s, Gipson says, cutthroat weren’t held in such special esteem. That’s all changed, as views of the importance of native species have matured. Nowadays, Game and Fish has special “creel limits”—essentially, how many fish can be kept by anglers and of what size—meant to keep cutthroat alive and to target nonnative trout. The state agency also touts its “Cutt-Slam,” which rewards anglers with a certificate if they’re able to document landing the four varieties that are still widespread in Wyoming: the Snake River fine-spotted, Yellowstone, Colorado, and Bonneville strains of cutthroat. (Two more used to live here, the west slope and greenback cutthroat, but they may have been wiped out.)

There’s also direct intervention meant to give cutthroat a fin up over nonnative counterparts throughout the Snake watershed. Brook trout are effective small-stream invaders with a track record of completely displacing cutthroat. They’ve basically completed the job in places like the Green River headwaters and countless other places around the West. In the upper Snake watershed, parts of the Buffalo Fork, Spread Creek, and even streams found in central Jackson Hole, like Game Creek, have been overtaken by brookies, which are native to the Great Lakes and Eastern seaboard.

But Game and Fish has poisoned brook trout out of four corners of the watershed, including lakes in the Teton Wilderness and tributaries of the Greys and Salt Rivers. Next on the agenda is Game Creek, planned for this summer. “Over the last few years in particular we’ve been concerned about species like brook trout,” Game and Fish’s Miller says, “because with climate change and the issues that could be coming at us in the future, we want to give cutthroat the best possible chance of persisting. Having an eye to the future is always an important piece of what we’re trying to do.”

The same threat looms with high-flying rainbow trout, an angler’s delight that’s native to the Pacific Coast and Alaska and even the lower Snake, but not anywhere in Wyoming. As close as the Snake River’s South Fork (downstream of Palisades Dam), rainbows are starting to dominate cutthroat, both by out-competing them for finite resources and by tainting the gene pool. Rainbows and cutties can crossbreed, creating “cutt-bow” offspring. Above Palisades, small populations of rainbows have held on in places like the Gros Ventre River near Kelly and in the Salt River—and there are no barriers ensuring they won’t spread.

Brown trout, a native Eurasian fish, dwell in the Snake watershed too; but, like rainbows, they’re largely confined to just a few places. The best bet to catch a brown is in Jackson Lake, Palisades Reservoir, and naturally fishless Lewis Lake, but they can also be caught in the Snake and Salt Rivers, especially during the fall spawning runs.

DURING GAME AND Fish’s fall 2019 fish survey of the Snake River, the 1 percent of non-cutthroat trout that Gipson, Miller, and colleagues stunned and netted consisted of 11 brown trout and three lake trout. Asked what became of the nonnative specimens, Gipson makes a garbled throaty sound, mimicking an empty radio channel. “They were removed,” he says with a smile. Death is the fate that nonnative trout meet when Game and Fish shocks and nets them out of creeks and rivers in the watershed.

The idea of killing nonnative trout to help out the natives doesn’t sit perfectly with everybody. “I’m tolerating it, but I’m still not overly thrilled by it,” longtime Jackson Hole outdoor writer and former fly-fishing guide Paul Bruun says. Brook, brown, and rainbow trout are all prized game fish throughout much of their range; accepting that they pose a grave threat to cutthroat and ought to be destroyed didn’t come easy to Bruun. He even wrote a Jackson Hole News&Guide column about it in 2015, titled “It’s hard to accept my poor trout thinking.”

Bruun hooked his first Snake River fine-spotted cutthroat 51 years ago, on the stretch of upper Flat Creek where the access road is so bad it’ll bust your struts. His initial excitement over a new species evolved into a lifelong obsession. Cutthroat are known for their voracity and willingness to take a dry fly from the water’s surface, but their habits also differ from more ubiquitous rainbows and browns. “You can take an expert, well-traveled trout fisherman and put him on a cutthroat river, and he’s going to be a step or two off,” Bruun says. “That’s what I appreciate about the cutthroat.”

The diversity and variability of streams and rivers in Jackson Hole are the “poster children” of what conservation and resilience to climate change are all about. “It’s all about genetic diversity, and what facilitatesgenetic diversity is diversity of environments. You have fish that are exposed to a lot of different environmental stressors.”

— Robert Al-Chokhachy, USGS researcher

There are various theories for why the Upper Snake’s native fishery has held up better than in other major river systems of the West. “There’s something about the Snake where, so far, cutthroat rule,” Jackson Hole Angler’s Ellerstein says with a knock on a wooden table. The Snake River basin in Wyoming is high elevation and it’s been fed by winter snowpacks that, to date, have held up relatively well as the atmosphere warms. There’s also a highly protected necklace of wilderness and national parks circling and feeding the watershed, helping ensure clean water and preventing development. Al-Chokhachy, the USGS researcher, says that taking out dams like the one on Spread Creek—he studied how cutthroat move upstream in the aftermath—will only help the watershed and its native trout. “It enhances the Snake because it offers another variant of a tributary,” he says. “Having each one of these streams be properly functioning is what makes the Snake that much more powerful.”

The diversity and variability of streams and rivers in Jackson Hole are the “poster children” of what conservation and resilience to climate change are all about. “It’s all about genetic diversity, and what facilitates genetic diversity is diversity of environments,” Al-Chokhachy says. “You have fish that are exposed to a lot of different environmental stressors.”

U.S. Forest Service ecological climatic modeling suggests that much of the Snake watershed’s higher elevation reaches will function deep into the 21st century as “climate refuge streams,” capable of harboring spawning cutthroat trout and their spawn and young. Still, looming threats weigh on Al-Chokhachy’s mind when he contemplates a warmer, drier future. Brook trout will continue to radiate outward from their many strongholds throughout the watershed. The future is also likely to be more favorable for brown trout and rainbows, which better tolerate warmer water than cutties.

Another concern is pressure from fly-rod wielding anglers partaking in a pursuit that’s growing evermore popular. The worry isn’t harvest but catching and then releasing fish into perilously warm water where they cannot recover. That’s not yet a problem in Jackson Hole, but there’s a good likelihood it will be down the road. Already, Montana fisheries managers implement routine “hoot owl” restrictions on rivers like the Madison, where fishing is banned after 2 p.m. when the water temperature exceeds 73 degrees for three days straight. Someday, rivers may need to be shut down entirely during the warmest times of year. “I think we’re naïve to think it’s not on the horizon,” Al-Chokhachy says. “When you walk in the lower portions of Pacific Creek, it’s pretty warm. And when it’s warm, what do fish need to do? Eat. In those situations, you’re just exacerbating these stressful conditions.”

Jackson Hole scientists, advocates, and anglers tasked with conserving the cutthroat aren’t resting on their laurels, but they’re also relishing a fishery that remains in outstanding shape today. And they’re trying to spread the word. “When you fish the main rivers in Montana—the Gallatin, the Madison, the Bitterroot—you’re not guaranteed to catch a cutthroat,” Trout Unlimited’s Steen says. “Even on the South Fork [of the Snake], you have a higher chance at catching a cutthroat, but you’re also going to catch lots of browns and some rainbows. But if you fish on this side, you’re almost always going to catch a Snake River cutthroat that’s genetically pure and evolved to be here, whether in the Snake, Hoback, Gros Ventre, or a little tiny tributary you have to hike a couple miles to get into.”

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is known for its relatively intact state, with protected land, functioning migrations, clean air and water, and the full suite of terrestrial wildlife that existed here historically. “Not that many people know that under the water, we also have something that’s similarly precious and unique,” Steen says. JH

Because of the dominance of fine-spotted cutthroat in the Jackson Hole watershed, the fly fishing in the area is different. “We work hard to educate clients about how special the cutthroat fishery is,” says Dave Ellerstein, the founder and owner of Jackson Hole Angler. “That’s part of our job, so they have an appreciation for it.” Photo by Neal Henderson

The Snake River in Grand Teton National Park. Photo by Bradly J. Boner

Workers use heavy machinery to remove the Spread Creek Dam in September 2010. Project organizer Scott Yates says removing the dam opened up an importantant tributary of the Snake just east of Grand Teton National Park. “All this habitat up here is like a hotel, just waiting for fish to check in,” he says. Photo by Price Chambers

An Idaho Department of Fish and Game fisheries biologists cradles a rainbow-cutthroat trout hybrid known as a cutbow that was caught with electrofishing equipment in the Snake River’s South Fork. Although this fish was released into a kid’s fishing pond and went on to live another day, rainbow trout and cutbows caught by Wyoming Game and Fish Department in Jackson Hole are usually killed in order to protect the native cutthroat trout population. Photo by Bradly J. Boner