Read The

Current Issue

Diary of a Dudine

Valley tourism one hundred years ago, as written by a tourist of the time

BY Mark Huffman

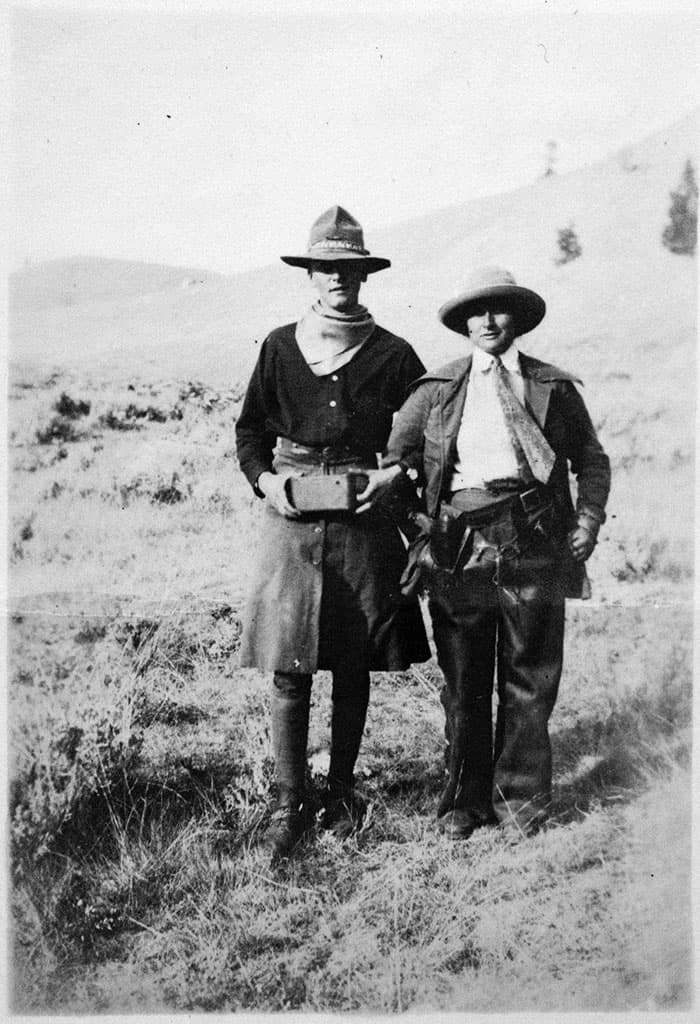

MOST JACKSON HOLE vacationers never get far from a paved road. But Edith Baily took her trip to the Hole before there were any paved roads to get away from. A century ago this summer, Baily, the twenty-one-year-old daughter from a good Philadelphia family, took a cowboy vacation and rode the high country east of Jackson hunting elk—she and five Jackson men.

As Baily later recounted in a typewritten memoir, Diary of a ‘Dudine,’ she traveled with Cal Carrington, the Hole’s most famous cowboy at the time and dude wrangler. She described herself as “a girl in a khaki hunting suit with big military pockets, knee length skirt, knickerbocker stockings, and high laced moccasin boots with her left leg slung over a gun in a scabbard.” She also called herself “an extraordinarily fortunate girl on the cayuse at the head of this cavalcade.”

In today’s Jackson Hole of five-star resorts and high-speed lifts, of regular jet service, spas, 170 restaurants, and all the rest of it, it’s difficult to imagine the valley and its tourism business in 1916. Then the first white settlement was only a bit more than twenty years old; the first U.S. census of Jackson, in 1920, put the population of the new town at 307. Tourism was mostly hunting and faux cowboying.

PRETENDING TO LIVE the cowboy life was rough by modern standards. On Sept. 12, 1916, dudine Baily, near the end of her three-month stay in the valley, and her companions set out from the Bar BC, founded in 1912 as the area’s second dude ranch.

The party rode Menor’s Ferry across the Snake River at Moose, then headed east past Blacktail Butte to Kelly, where they stopped for lunch. The settlement “boasted a store, church, and school for the nearby ranchers.” From there they headed for Sheep Mountain, better known today as the Sleeping Indian.

Edith showed her stuff when she had a mishap right off. “In passing between two large rocks, Jay Jay, my horse, tripped, lost his balance and fell heavily to the left, crushing the calf of my leg against the rock.” Back in the saddle after ten minutes, “My leg pained horribly and I felt sick and faint and, had not custom blessed the weary traveller with a horn on his saddle, I doubt if I could have sat the horse.”

As Jay Jay stumbled up the rocky slope, Edith was spooked when four horses behind her slipped over a steep slope and crashed downward. But she knew she had to be tough.

“My nerve was thoroughly shattered by now and I almost burst into tears,” she wrote. “But crying is a pastime one does not indulge in when ‘paling it’ with five men.”

With her companions taking potshots at coyotes and hawks, Edith spent nine hours in the saddle before she settled down for the night. In ensuing days she finally, after many wrong shots, managed to get the elk she was determined to bag.

EDITH BAILY WAS married within two years, and moved with her husband, Magruder Dent, a World War I flier, to Greenwich, Connecticut, where they became part of the Social Register scene. They had two sons and two daughters. The sons, when still in their early twenties, commanded ships in the Pacific during World War II. One, Frederick Dent, served two years as Secretary of Commerce under President Nixon and two years as U.S. Trade Representative for President Ford.

Edith Dent bred and raced horses—she had about sixty over the years—and in 1964, her Mr. Moonlight was seventh in the Kentucky Derby.

Magruder Dent III, Edith’s grandson, isn’t surprised to hear about her foray into the Jackson Hole backcountry. Her reputation among her family was as “headstrong—definitely a force to be reckoned with,” the University of Virginia administrator says. “She was someone who did what she wanted to do. She did not really let anyone get in her way. If she was going to do something, she was going to do it.”

Her family isn’t sure if Edith ever made it back to Jackson Hole. She died in 1987, at the age of ninety-three.