Read The

Current Issue

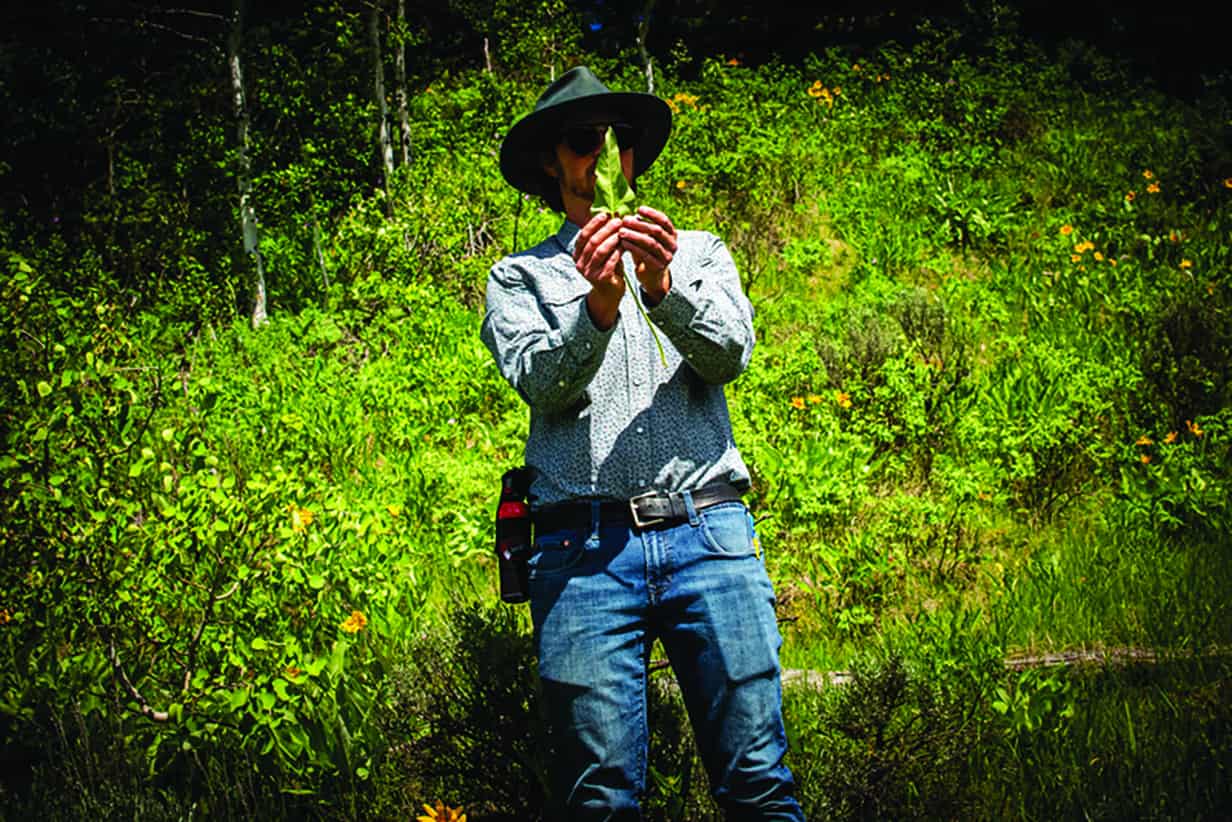

Form & Function

Landscaping with native plants is good for the ecosystem and can be beautiful.

// By Jim Mahaffie

When Frances Clark, an avid gardener, moved to Wilson from New England, she found Wyoming’s plants and terrain completely different. Rather than planting what caught her eye at a local nursery, like lavender or echinacea, or what grew for her in New England, like hydrangeas or flowering crabapples, she spent years hiking to see local wildflowers and learning about them. And then she planted her gardens and yard with species she knew from the local landscape.

Jackson Hole, and the larger Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, would benefit from more homeowners doing what Clark did. “Natives have so much to offer versus nonnative species,” says Teton Conservation District’s executive director Carlin Gerard. “We need to think of our landscapes as wildlife habitat, where we want the bugs and birds. Gardens can be about beauty, but we have a responsibility to create and retain habitats here in Jackson Hole.”

Clark says, “You like to grow [natives] because they’re beautiful and support wildlife, especially pollinators. That, in turn, helps support birds. Fruits are eaten by migrating birds and mammals. Moose love our red twig dogwoods.” Trevor Bloom, a community ecologist with The Nature Conservancy and a member of Teton Botanical Garden, which inspires and educates about the importance of conservation, preservation, and sustainability, says, “There’s plenty of beauty and hardiness in the more than 1,350 native plant species that do well in Teton County landscapes.”

The plants native to the northern Rockies adapted over millennia to the unique environment and climate and to complement other plants and animals. Native plants stabilize soil, filter water, and are preferred food sources for wildlife. Flowering native plants feed pollinators like ants, bees, beetles, butterflies, flies, birds, hummingbirds, and moths. “Thousands of species of flies, beetles, wasps, ants, spiders, hummingbirds, and bats are essential for keeping our environment healthy. Many of these are frontline defenders in keeping garden pests in balance,” says Morgan Graham, geographic information system/wildlife specialist with TCD. Native plants don’t require a lot of water, mowing, fertilizer, or pesticides—and they can often handle being grazed on and bounce back.

The Nature Conservancy and Teton Conservation District classify native plants as those that grew in the ecosystem before European contact and the Homestead Act of 1862. Many homesteaders planted nonnative alfalfa and other grains for livestock feed, and planted kitchen gardens with nonnative plants like mint, oregano, and chives. Toadflax, an ornamental plant popular in gardens on the East Coast and in Europe, is thought to have been brought to Yellowstone in the 1890s via home gardens planted by residents of Mammoth Hot Springs Officer’s Row. Nonnative plants can also arrive here in hay, dried mud on vehicles, imported topsoil or sod, or on the bottoms of hiking boots or golf shoes.

Mismanaged and manicured landscaping can be a big source of nutrient pollution in Fish Creek and the Snake River.”

— Carlin Gerard, Teton Conservation District’s executive director

Today, toadflax and almost 70 other nonnative species—including thistle, cheatgrass, and spotted knapweed—pose significant threats to the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem because they reproduce quickly and out-compete native species. Every spring and summer, Teton County Weed & Pest sprays herbicides against these. Not all nonnative plants pose active threats to our ecosystem, but that doesn’t mean they’re benign. Fertilizer and pesticides often needed for nonnative plants to survive here can be harmful to the environment. “Mismanaged and manicured landscaping can be a big source of nutrient pollution in Fish Creek and the Snake,” says TCD’s Gerard. Nonnative plants that fall into this category include perennial cornflower and climbing nightshade, which is poisonous for humans and livestock yet can still be found throughout the valley.

To see what can and should go in your garden, look around. Lupine fills meadows in late spring. Balsamroot covers hillsides in yellow blooms in June. Clematis blooms all summer. Indian paintbrush (Wyoming’s state flower) is ubiquitous, but in a home garden, it has to be planted with thought. A hemiparasitic plant, it gets some of its water and nutrients from a host plant, like penstemon or sage.

In a planter, depending on the amount of sunlight it gets, you can mix nonnative annuals like geraniums, petunias, daisies, and vinca vines with native wildflowers like blue flax and shrubby cinquefoil. “Part of the challenge and fun of incorporating native plants into your landscape is doing some homework, experimenting with what you can find, and cultivating patience to see what establishes well on your site,” says Graham. Clark, the Wilson gardener who noted the area’s native plants before planting her garden here, says her work took a few years to get established and some plantings are still works in progress. “Some natives aren’t the showiest for the first few years,” she says. “You need a level of trust and commitment. But there’s a great payoff—and that’s the glory of gardening!”

Getting Started

Find the Teton Conservation District’s Pocket Guide to the Native Plants of Teton County, Wyoming, and a Native Plant Resource Guide, produced in collaboration with The Nature Conservancy, at tetonconservation.org/native-plants.

High Mountain Pollinators & Bees, in Etna, Wyoming, partners with Sheridan-based Piney Island Native Plants to offer homeowners in Teton County seven different varieties of native pollinator-friendly plants at wallet-friendly prices: nettle leaf hyssop, pearly everlasting, rocky blue mountain columbine, showy fleabane, showy goldeneye, Rydberg’s penstemon, and goldenrod.

The Greater Yellowstone Botanical Tour at the National Museum of Wildlife Art was created to showcase native plants. A 30-stop, ADA-accessible audio tour explains their importance and connections with the area’s ecosystem. Doubtful that native plants can make for beautiful planters? End your audio tour at the planters on the deck of the museum’s restaurant, Palate. “As with many native plants, they don’t always look great the first year, but they’re starting to fill out,” says Bloom, who worked on the planters.

Bloom’s Best Bets

Trevor Bloom, community ecologist with The Nature Conservancy and member of Teton Botanical Garden, shares five native species you can plant that will make your yard gorgeous while benefiting wildlife and the landscape.

Quaking aspens provide important shade and habitat for wildlife from birds to elk and bears—moose preferentially feed on the twigs—and can help form natural firebreaks when mixed in with conifers that burn more readily.

Woods’ rose hips, the fruit of the rose flower, are highly valued by birds and other wildlife and look absolutely beautiful in home gardens. They are also super hearty and easy to grow, with deep pink and yellow flowers that appear in clusters on the perennial shrub.

Shrubby cinquefoil is one of several potentilla species native to Jackson Hole. It’s very easy to grow and available at many local and regional nurseries. Low-maintenance and drought-tolerant, the yellow flowers bloom for several months and attract an array of cool pollinators. Birds eat the seeds, blooms attract butterflies, and deer and rabbits tend to avoid them.

The native sticky geranium produces a beautiful array of purple and pink flowers that are sure to please the eye and any passing butterfly. Our natives (sticky and Richardson’s) are true geraniums, where the popular ornamental “geraniums” are more often pelargoniums and not native to this region.

Colorado blue columbine is a spectacular wildflower, and it grows very well in home gardens. Very adaptable, this flower can be both blue and white, or any combination of the two colors. Plants will self-seed, and the nectar feeds insects and hummingbirds. JH