Read The

Current Issue

No Lifts Necessary

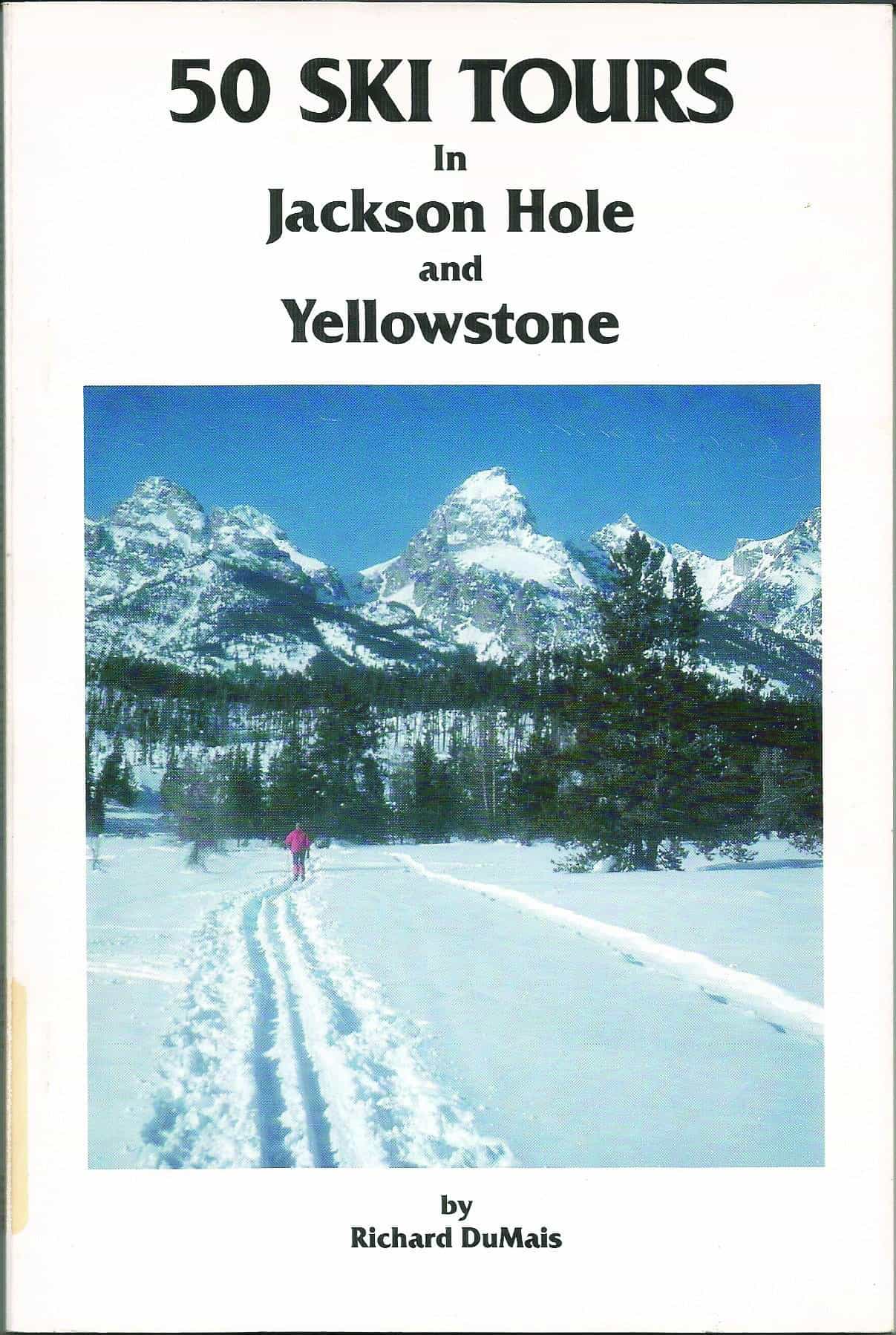

People skied in Jackson Hole long before the arrival of ski lifts…and they still do. Today it’s called ski touring, and it is more popular than ever.

// By Dina Mishev

A s I hike up a well-established bootpack on Mt. Glory, a hulking peak rising 2,000 vertical feet just north of Teton Pass, my headlamp is one light among dozens. Each spotlight is a person carrying a backpack with avalanche gear like a probe pole and snow shovel inside and a snowboard or skis strapped to the outside. We’re “dawn patrolling,” mountain-town speak for squeezing in a ski run, preferably of powder, before the start of the work day. A couple of times when I’ve had family and friends visiting with the fitness and skills required to dawn patrol—“dawn patrol” is both a noun and a verb—I take them. What was a regular weekday morning for me was the highlight of their vacation.

Backcountry skiing (also known as ski touring) is a type of skiing done in areas in which there are no lifts, no ski patrol, and no avalanche control. It requires specialized gear, avalanche awareness, and a willingness to climb a mountain before skiing it. It’s not unique to Jackson Hole; over the last decade, and particularly since the start of the pandemic, ski touring has grown tremendously in popularity. Between August 2020 and March 2021, sales of backcountry skis, boots, and bindings were up 115 percent compared with the same period over the previous years, according to the industry trade group Snowsports Industries America.

While ski touring isn’t unique to Jackson Hole, Jackson Hole is unique in the U.S. for the quantity and quality of its backcountry skiing, and its relatively easy access. If you’re fast on the bootpack up Glory, you can wake up, dawn patrol, and be at work in two hours. “Jackson Hole is unique in the backcountry skiing world because many of the ranges are sized and shaped just right to allow a lifetime of one-day outings,” says ski guide, author, and historian Tom Turiano. “These outings vary widely from the most mellow to some of the most extreme anywhere.” Equally rich is the history of ski touring in Jackson Hole. Books have been written about the topic (see sidebar); here we only have room to share the broadest of strokes.

People have ski-toured in Jackson Hole since homesteaders arrived here in the 1880s. For decades, it wasn’t done for recreation, but necessity. In the early 1890s, there wasn’t yet a post office in Jackson Hole. The nearest post office was in Driggs, Idaho, a 60-mile round-trip up and over (and back up and over) Teton Pass. In summer, this was done by horse, but in the winter, volunteers skied to get the mail. Homesteaders on Mormon Row sometimes skied the 10-ish miles into Jackson for dances or supplies.

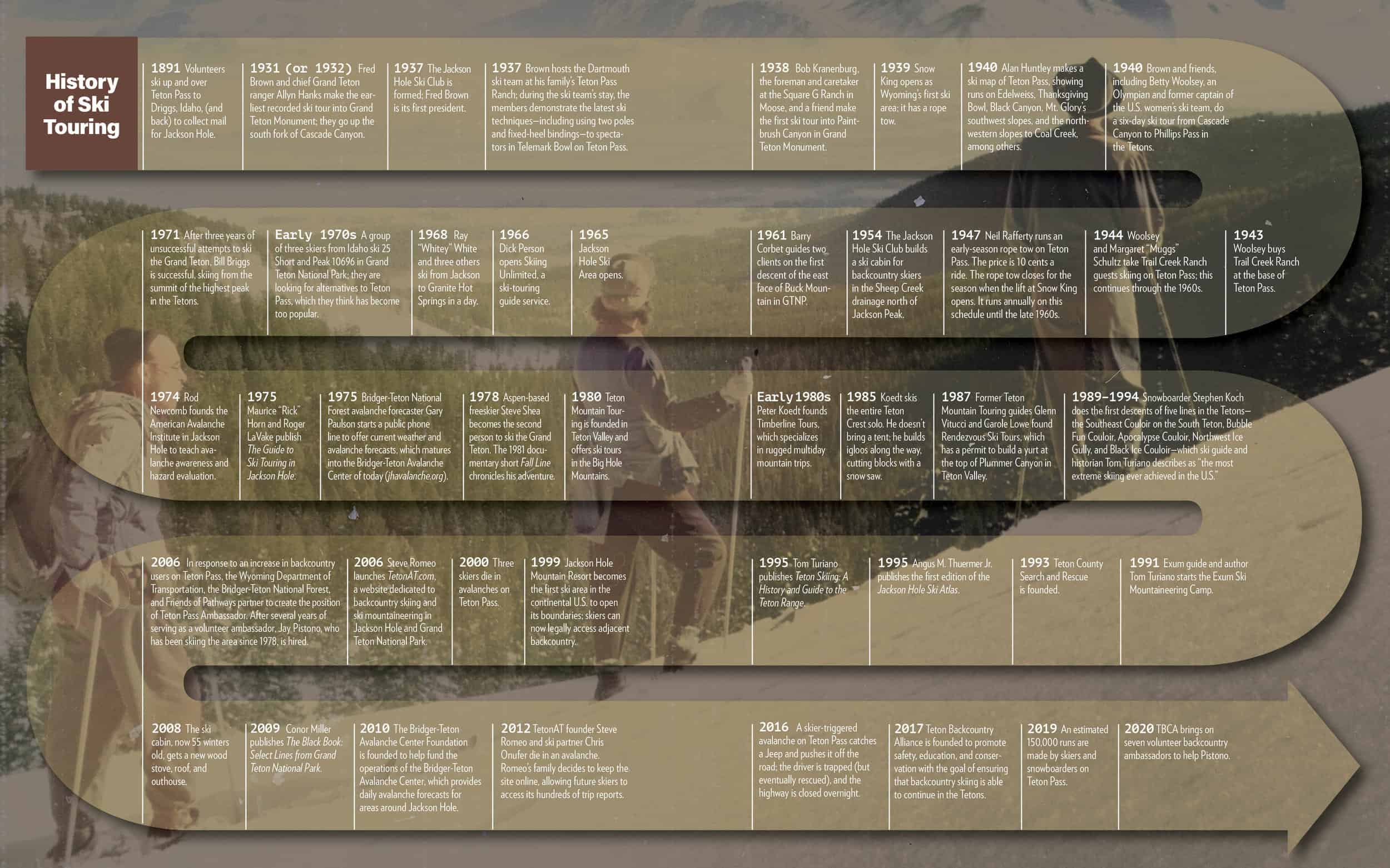

But it didn’t take long for ski touring to be done for fun. Locals made turns on Teton Pass in the 1920s and 30s. A 1940 map of the pass shows many of the same runs people ski today. For decades, a group came and stayed at Trail Creek Ranch at the base of Teton Pass for one month and skied the pass almost every day. And for decades, Margaret “Muggs” Schultz, who turns 94 in 2023, guided these skiers. “A group would go out before breakfast; we’d hitch a ride up in the mail truck and ski down to the ranch,” she says. They’d be back at the ranch in time for breakfast. After breakfast, a larger group would be driven to the top of the pass in the ranch’s ski bus, and they’d ski a different run down. “We never worried about running out of powder,” Schultz says. “There wasn’t anyone else up there.”

While some people skied powder on the pass, others used their skis as a way to explore Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks. Local adventurers did multiday cross-country ski tours in the Tetons starting in the late 1920s. It wasn’t until the 1960s that skiers began looking at peaks in the park as ski objectives. And then, on June 15, 1971, Bill Briggs blew everyone’s mind when he successfully skied the Grand Teton. “That recalibrated everyone’s idea of what was possible,” says historian Tom Turiano, who has backcountry skied around Jackson Hole since 1985.

Briggs skiing the Grand wasn’t remarkable only for its audacity, but because it introduced ski mountaineering—a mix of snow climbing and skiing—to North America (it was already happening in Europe). The argument can easily be made that Briggs is the father of North American ski mountaineering; he’s undisputedly the father of ski mountaineering in the Tetons. (Skiing the Grand was only one of Briggs’ many achievements; in 2009 he was inducted into the U.S. National Ski Hall of Fame.) “You build on the successes and failures of your predecessors,” says Turiano. “We knew Barry [Corbet] had skied the East Face of Buck, so we thought, ‘let’s go and ski that.’ We knew [Doug] Coombs skied the Sliver, so that is a thing to do. The pace of route development accelerates. In the Tetons, the classic extreme routes have become so standard that to take it a step farther is really taking it a step further. The skill and fitness levels of the skiers doing new things today are to the point of total mastery of the sport.”

It’s not just the lines people are skiing in the backcountry that have changed, but the number of people who are backcountry skiing. Angus Thuermer, a Teton Pass skier since 1978, thought Teton Pass was “over” in the early 1990s. “I was up there one day, and it was all tracked out,” he says. A writer, editor, and photographer, he had been holding off on publishing his book Jackson Hole Ski Atlas for several years. He says “the Teton backcountry was somewhat of a secret.” He didn’t want to be the one to blow it up. “I didn’t want my friends to get upset at me,” he says. But after seeing it all tracked out, “I thought, ‘I might as well publish the Ski Atlas,’” he says. Jackson Hole Ski Atlas was published in 1995.

Pass crowds in the 1990s were quaint when compared to today’s, though. Teton Backcountry Alliance, a nonprofit advocacy group, estimates that over each of the past several winters, more than 150,000 runs have been taken on Teton Pass. Most of these are uneventful, but fights have broken out in the parking lot between cars waiting in line for a parking spot and also on the Glory bootpack, where the speeds of hikers can differ vastly. Skiers and snowboarders have triggered avalanches that have run down to Wyoming Highway 22, which more than 5,000 cars commute over every day, and closed the road to traffic. More than one dozen skiers have died in avalanches. Something that in the 1990s seemed as likely to happen as a T-Rex bootpacking up Mt. Glory—that the Wyoming Department of Transportation would stop plowing the parking lot at the top of Teton Pass, effectively ending the easy accessibility that makes skiing there so popular—is now a topic of discussion.

Thuermer, who still skis the Teton Pass backcountry says, “In one sense [Teton backcountry skiing] is way over now. But in another sense, it is still going strong. It is just done by different people at different times. And it is still the greatest, but don’t tell anyone that.”

The Books Backcountry guidebooks over the years

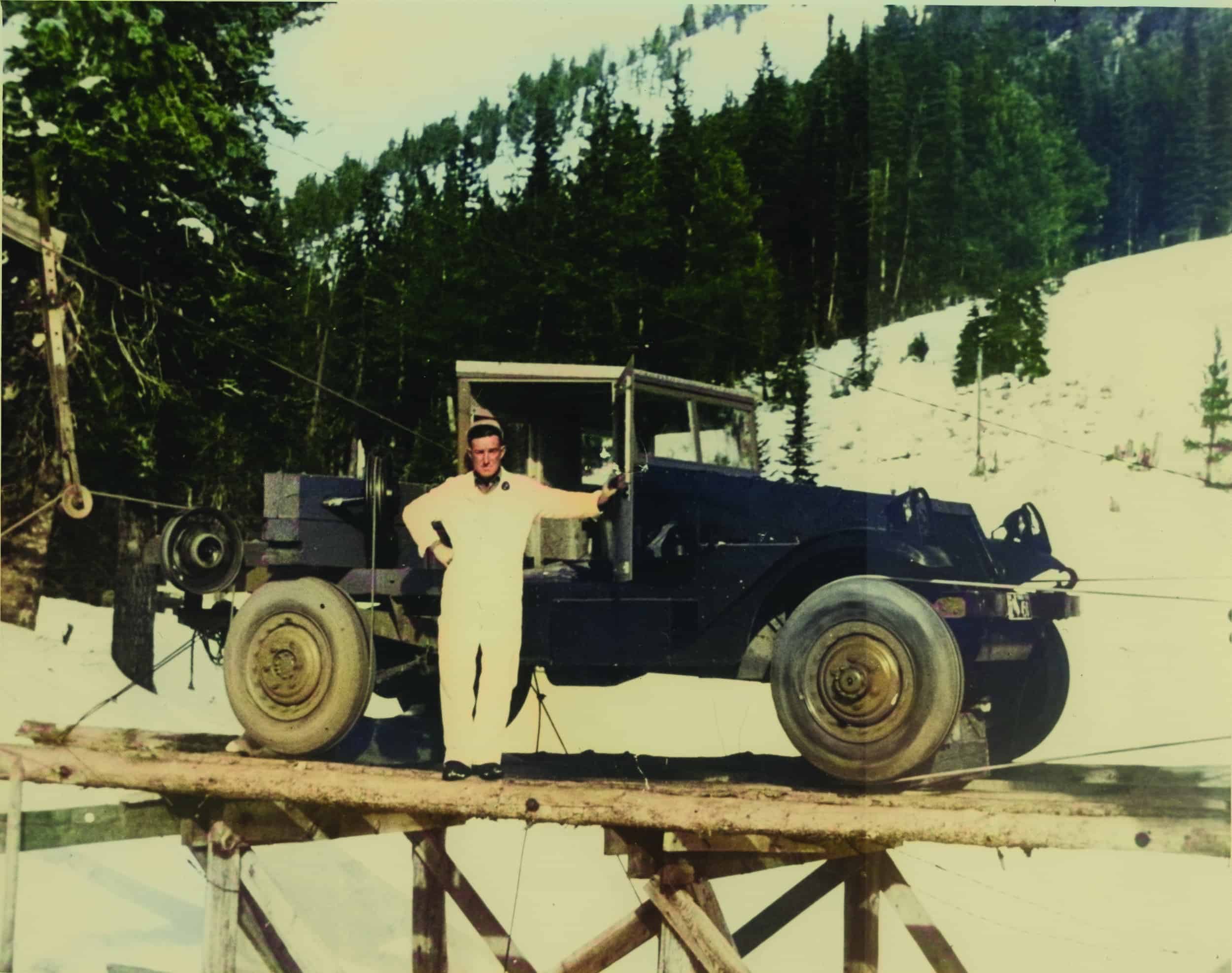

THE GUIDE TO SKI TOURING IN JACKSON HOLE

1975, out of print

Maurice “Rick” Horn and Roger LaVake

With the exception of the Grand Teton, the 20-some tours in this guide are, by today’s standards, cross-country ski adventures rather than backcountry skiing. Tours include Shadow Mountain, Bradley Lake, and Cache Creek. And the authors only include the Grand Teton, which, when this guide was published, had only been successfully skied once, as a joke. In its description they write: “SPECIAL NOTE: This difficult and hazardous tour has only been done once in the history of skiing—by Bill Briggs of Jackson on June 16, 1971.” They end the description by wishing anyone attempting this ski good luck.

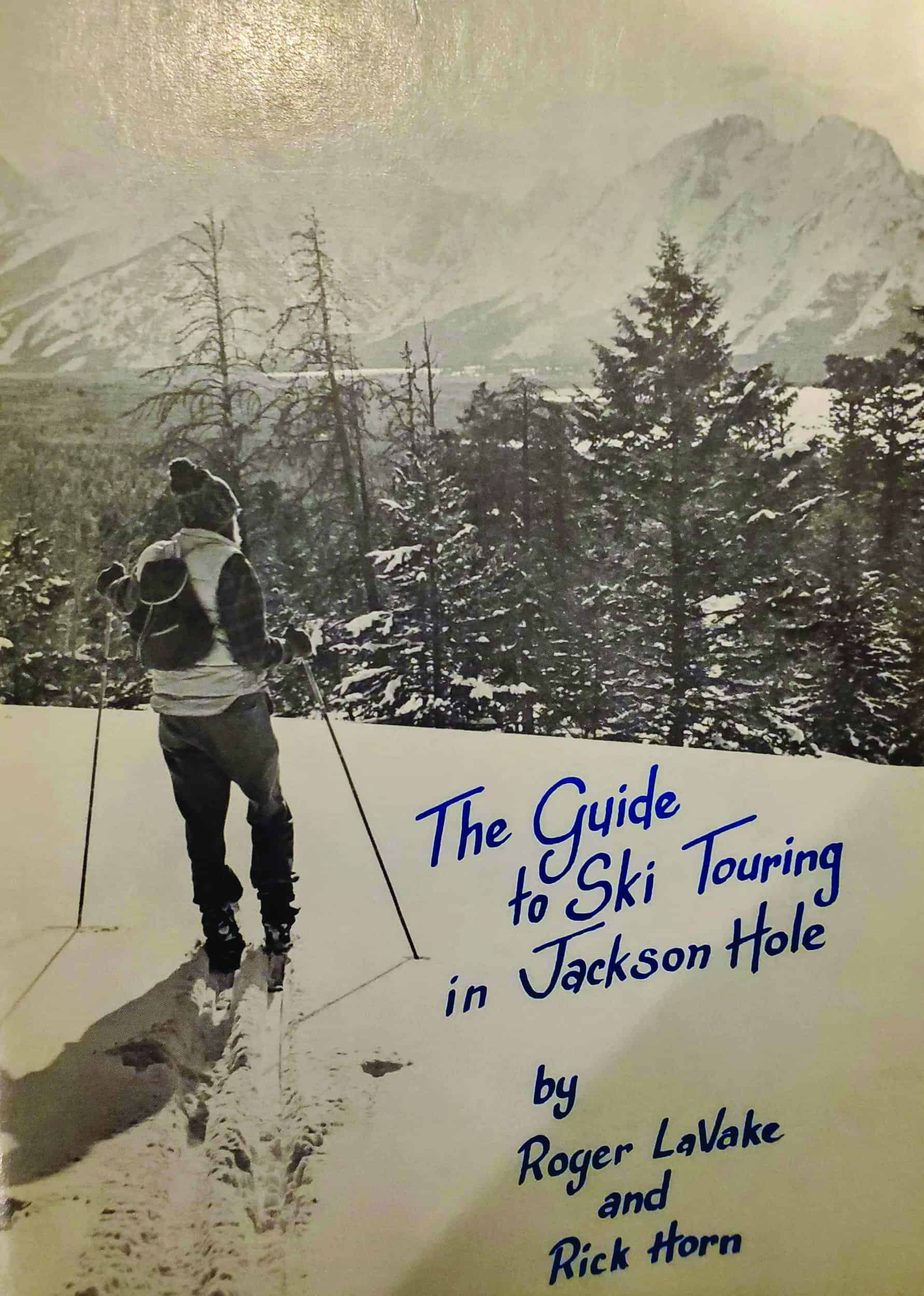

50 SKI TOURS IN JACKSON HOLE AND YELLOWSTONE

1990, out of print

Richard DuMais

Similar to the 1975 guidebook, DuMais’s book focuses mostly on ski tours rather than on downhill turns. In the introduction, he writes, “… this is a land of superlatives for winter sports enthusiasts. But it is to the cross-country skier more than anyone else that this vast region extends the greatest range of possibilities.” Tours include many of the same ones in the Horn/LaVake book, just with greater detail, and DuMais also expands into Yellowstone.

JACKSON HOLE SKI ATLAS

1995, fifth edition available early winter 2023

Angus Thuermer, Jr.

Thuermer, the former editor of The Jackson Hole News and, later The Jackson Hole News&Guide, says he held off on publishing this book for several years after he had all of the photography. This was the early 1990s and, “the Teton backcountry was somewhat of a secret,” he says. The atlas—a 40-page collection of 37 images from Teton Pass, Snow King, JHMR, Grand Teton National Park, and Grand Targhee—was only published after Thuermer went up to ski the pass one day in the mid-90s and it was all tracked out. “I said, ‘it’s over, might as well publish the Ski Atlas.’” The book is not a guidebook, though. Thuermer says: “It was never intended to be. You had to figure out how to get there and how to get back and how to get down. It is ski porn in one respect.” Thuermer’s images were taken not looking up from the bottoms of runs, but, thanks to the use of small aircraft, looking across at runs. “It’s a much better view than the foreshortened one you get from looking up from the bottom,” he says.

TETON SKIING: A HISTORY AND GUIDE TO THE TETON RANGE

1995, out of print; find used copies online

Tom Turiano

Turiano spent seven years working on this 221-page book that, as its title suggests, is as much of a history of skiing in the range as a guidebook. “Right away, I started digging into the history,” Turiano says. “I’d call some people and ask about their skiing adventures and then they’d tell me, ‘oh, you need to talk to so-and-so,’ and then I’d cold call them and tell them what I was doing. I’d send everyone a questionnaire and ask them to fill out the peaks that they had skied.” (Turiano still has all of these filled-out questionnaires in his archives.) The routes in the book range from mellow valley tours to you-fall-you-die couloirs. Although Turiano wrote Teton Skiing as more of a personal project than because he thought there was a need for a guidebook, “people noticed it,” he says. “And people I didn’t interview came out of the woodwork to tell me the peaks they had skied when.” Turiano has kept all of these notes and might incorporate them into a future book, Jackson Hole Backcountry Skier’s Guide: North.

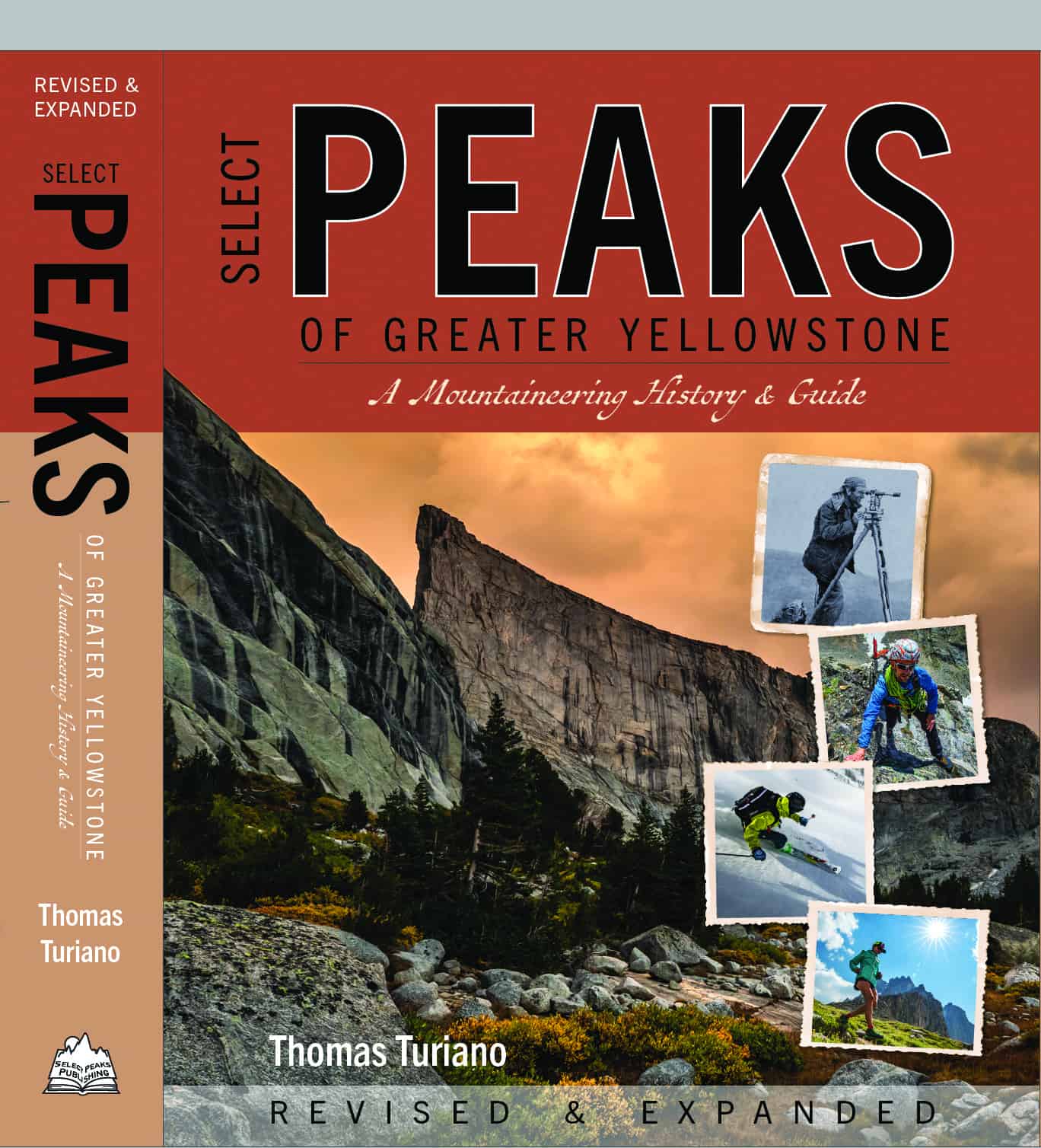

SELECT PEAKS OF GREATER YELLOWSTONE: A MOUNTAINEERING HISTORY AND GUIDE

2003, out of print; a second edition is coming in summer 2023

Tom Turiano

Called “The Bible” by TetonAT.com founder Steve Romeo, Tom Turiano’s second book includes the same mix of history and route descriptions as his first book, but broadens his subject matter from the Tetons to the 15-million-acre Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Turiano’s eponymous “select peaks” are 107 mountains across the Madison, Gallatin, Beartooth, Absaroka, Wind River, Gros Ventre, Wyoming, Salt River, Snake River, and Teton Ranges. Copies of this book, which has been out of print for at least a decade, call sell for upward of $400 on Amazon. Look for a second edition in summer 2023.

THE BLACK BOOK: SELECT LINES FROM GRAND TETON NATIONAL PARK

2009, from $47, available at blurb.com

Conor Miller

Miller, who worked at Alpinist magazine in the early 2000s, did this book because, he says, “I loved the other guides, but felt the beauty of the lines was missing. I would be mesmerized by them in person, and there was nothing to look at when I got home from skiing.” Because of its focus on images and purposeful lack of text, it’s more accurate to call The Black Book a picture book than a guidebook. Miller’s photography is inspired by the work of photographers including John Scurlock and Bradford Washburn, and the aerial images in The Black Book—including of Hidden Couloir (Thor Peak), Amora Vida (South Teton), and Fallopian Tube (Mt. Woodring)—are artistic in addition to being inspirational. Miller shied away from written descriptions because, “I didn’t want to tell people how to get anywhere or have any words that someone might use to make a bad decision,” he says.

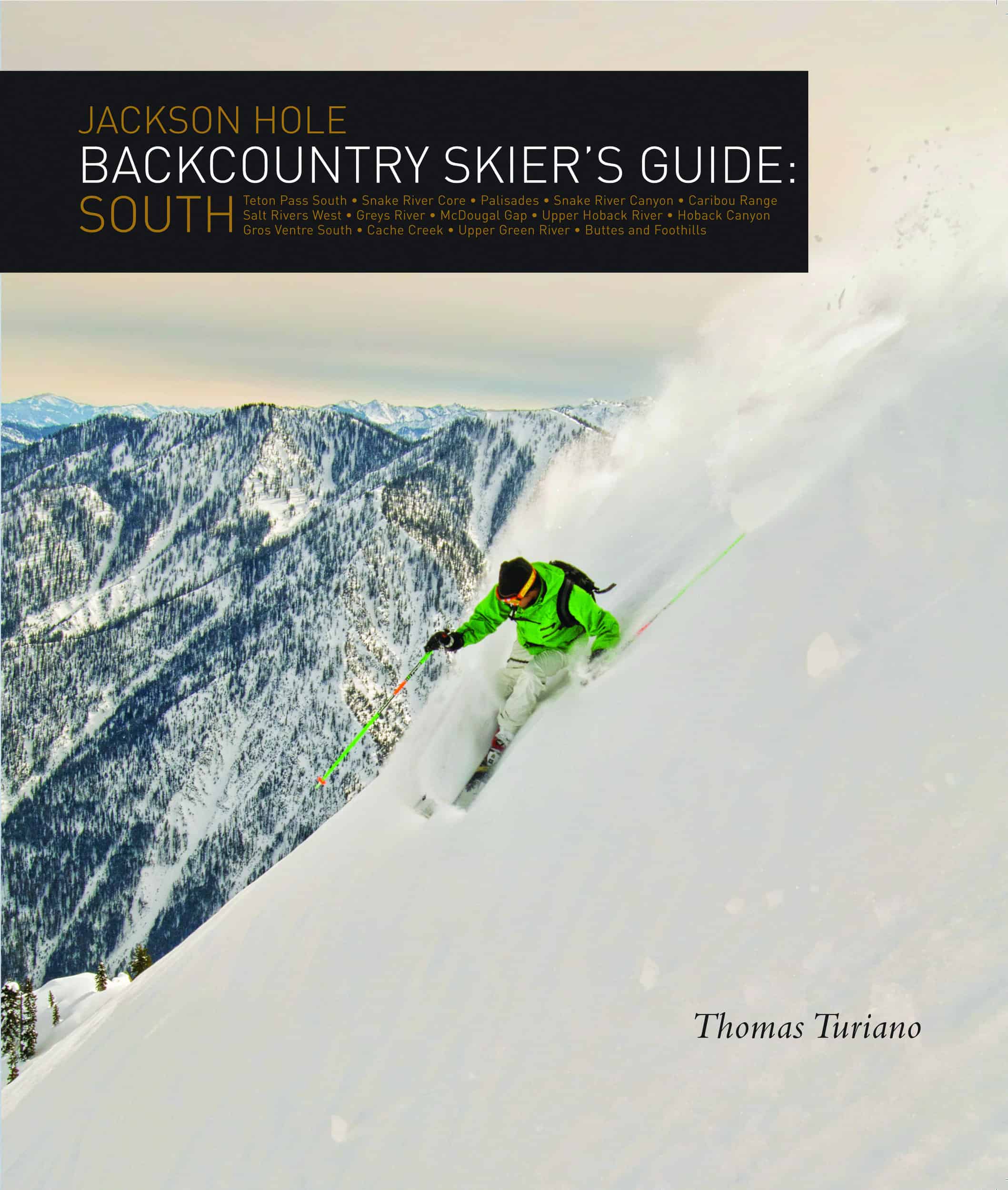

JACKSON HOLE BACKCOUNTRY SKIER’S GUIDE: SOUTH

2014, $70, available at thomasturiano.com

Tom Turiano

Covering upward of 1,000 routes in the southern Tetons, Snake Rivers, Caribous, the western Salt River Range, the southern Gros Ventre, and the southwestern Winds, this 406-page book caused Bill Briggs, the first person to ski the Grand Teton and a member of the U.S. National Ski & Snowboard Hall of Fame, to call Turiano a “visionary” among backcountry skiers. But, with geology and history mixed in with route descriptions and 500+ photos and virtual renderings, this is the rare guidebook that’s not just interesting to skiers. Anyone interested in the history of the mountains around the valley will enjoy this book. Turiano says he wrote JHBSG: South, which does not include the areas of the Tetons most popular with backcountry skiers (north of Teton Pass), “because the Pass was getting crowded and [Grand Teton National Park] was getting crowded and I thought people would be interested in expanding their horizons a bit. There is so much more out there to ski.”

SELECT PEAKS OF GREATER YELLOWSTONE: A MOUNTAINEERING HISTORY AND GUIDE

Second Edition, revised and expanded coming summer 2023

Tom Turiano

Although this has the same title as Turiano’s 2003 book, it is more than just a second edition of Select Peaks. “It’s a complete rewrite,” Turiano says. The “select” peaks included in the book are the same 107 as in the original, but with “many new routes added to the peaks,” Turiano says. Also different is that Turiano eliminated the 80-page general history section that started out the first edition and instead added “Deeper Dive” sections interspersed throughout the book. “Many of these deeper dives are completely new information, new research, and new writing,” he says. Finally, the photos in this book are in color (versus the black and white of the first edition). JH