Read The

Current Issue

Living History

Backcountry cabins are a part of Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks’ human history. You can visit them, but no spending the night.

By Kylie Mohr

MOTHER NATURE DID most of the work in creating Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks. But rangers and trail crews put in blood and sweat to preserve her work—and to allow you to better experience it—trudging through snowdrifts to foil poachers and performing the backbreaking labor of trail building. While doing so, they’d spend nights sheltered from the elements in cabins scattered across the rugged landscape, some of which are still standing and used today. A few are tucked away amidst meadows bursting with wildflowers at summer’s peak; others are prominently located at trail junctions or snuggled up against gently babbling streams.

“It’s part of that visual history that showcases the traditions of public land management,” says Denise Germann, Grand Teton National Park (GTNP) public affairs officer, of the cabins. “They’re awesome visual reminders of our history that we are still using today.” Yellowstone National Park historian Alicia Murphy says she gets questions about the cabins all the time, mostly via email or phone, although some curious folks stop by her office. Everyone’s wondering what the cabins were for and when they were built, she says. “People are really intrigued by them. They come across one [while] hiking and they just think they’re fascinating.”

At one time, GTNP had at least a dozen backcountry cabins. Today, seven remain—two newer ones, from the 1950s, in Moose Basin and Upper Berry Creek, and five listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The historic cabins are in Cascade Canyon, Death Canyon, the Leigh Lake area, Lower Berry Creek, and Upper Granite Canyon. Yellowstone once had 48 backcountry cabins. Today 35 still stand; 26 are on the National Register of Historic Places. The nine not on the national register were built within the last 50 years or moved and/or modified substantially from their original form.

In both parks, employees like rangers and trail and fire crews still use these cabins. The public can’t overnight at them, but Yellowstone’s Murphy says she knows “a lot of people like to sit on the decks and porches and eat lunch. I know I’ve done that. They’re kind of a romantic structure to come across in the wilderness.”

IN THE YEARS following Yellowstone’s founding in 1872, civilian superintendents struggled to protect animals inside the park, including elk and bison. On the western plains, the 1870s and 1880s were a heyday of commercial bison hunting; several hundred commercial hide-hunting outfits operated at any given time during this period. Individual hunters were known to kill as many as 100 animals a day.

This situation in Yellowstone changed when the U.S. Army took over management in 1886. Specifically to address the poaching of animals within the park’s borders, the Army developed a system of soldier outposts to aid in patrolling. The cabins were constructed mostly with materials found in the area like logs, stones, and sod. Glass (for small windows) was carried in by horses or humans. The cabins were usually only one or two rooms. They were not manned year-round but used for a night or two by patrols passing through an area. In the beginning, floors and roofs were of sod, but concrete floors and cedar shingles eventually replaced the dirt. Covered porches served as space for firewood storage.

In Yellowstone the Army built 17 cabins, 11 of which were standing by 1900. These early structures were referred to as “snowshoe cabins” because they were approximately 16 miles apart, about the distance a ranger could travel in one day in the winter on snowshoes or cross-country skis. “They kept these cabins stocked,” says Zehra Osman, Yellowstone National Park cultural resource specialist and landscape architect. “They were ready for a person to come in the door and have everything available they needed to stay there so they didn’t have to carry their belongings. It made it easier to do those patrols.” Reports from the time suggest patrols could be up to fifty miles in distance and 10 days in duration.

After the Army turned over the management and protection of Yellowstone and its resources to the newly created National Park Service (NPS) in 1918, cabins continued to be built to fill in the blanks. A policy change in the 1940s restricted the cutting of trees for cabin construction; cabins built after that time were wood framed. The NPS built its 31st and last cabin in the park in 1973.

South of Yellowstone, Grand Teton National Park administrators had the idea for backcountry cabins at the time the park was founded in 1929, according to a 2008 report from the University of Wyoming’s National Park Service Research Center. Fritiof Fryxell, a geologist and the park’s first ranger/naturalist, and other early park managers were keen on the idea of cabins. Fryxell proposed a backcountry trail system and believed the cabins would support crews, offer shelter for patrols to protect wildlife, and serve as base camps for fire fighters in remote areas.

The Park Service constructed the Leigh Lake Patrol Cabin between 1930 and 1932; also in 1932 the Civilian Conservation Corps built the Moran Bay Cabin. Today the latter is in GTNP, but in 1932 it was part of the Teton National Forest. In 1935, the U.S. Forest Service built the Hot Springs Patrol Cabin on the west shoreline of Jackson Lake, another area of the Teton National Forest that eventually became part of GTNP. The Hot Springs Cabin remained standing until at least 1949; the date of its final demise is unclear. The Moran Bay Cabin stood until 2000, when it was consumed by fire.

In 1938, GTNP trail crews were busy building many of the trails still used by hikers today. Crews slept in tents, which then-GTNP superintendent Guy Edwards noted weren’t ideal living conditions due to the park’s heavy rain and snow. He advocated for additional cabins, saying they would provide more safety and also result in crews spending more time building trails. The cabins were still seen as helpful for rangers and fire crews, as well. While Grand Teton never faced the poaching pressure Yellowstone did, in the 1930s hunters were illegally harvesting animals near the park’s western boundary and trappers illegally catching marten and beaver, particularly in Granite Creek.

Not all intended cabins panned out. In 1941, plans for structures in Alaska Basin and Paintbrush Canyon were cancelled. But by 1950 there were at least six official backcountry patrol cabins, and also a handful in and around Webb Canyon and Owl and Berry Creeks. It’s unclear who built the latter, though it’s thought to have been miners, hunters, and/or “tuskers,” who hunted elk for their teeth, most of which they made into jewelry.

The last new cabins built in GTNP—small shelters at Moose Basin and Upper Berry Creek—date to the 1980s. For the Upper Berry Creek structure, logs were flown in by helicopter. An existing plywood shack nearby was turned into an equipment cache. It’s possible that renowned conservationist Adolph Murie used this shack as he and others conducted elk research in the area in the 1940s and ’50s says Katherine Wonson, director of the Western Center for Historic Preservation. This educational and resource center is dedicated to the preservation and maintenance of cultural resources in western national parks. But there’s not enough evidence supporting this theory for the structure to be eligible for historic designation, Wonson says.

See For Yourself, Grand Teton National Park Cabins

Berry Creek Cabin

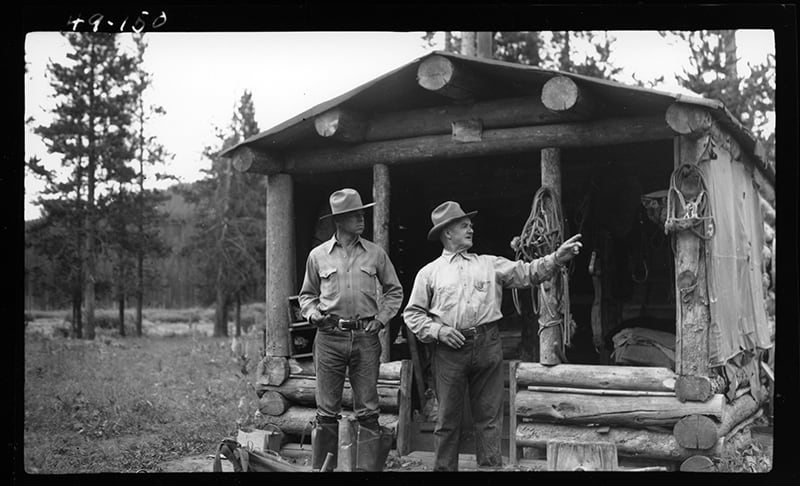

Photo Courtesy of Grand Teton National Park Archives

What? A 1949 National Park Service inventory of cabins details a one-room, one-story, 144-square-foot cabin near the mouth of Berry Creek. The survey claims the cabin was built in 1910 by the U.S. Forest Service and remodeled in 1938. But this is not the cabin now found at Lower Berry Creek. Today’s cabin dates from the 1950s. Historical sources point to a cabin on the Feuz Ranch near Spread Creek being disassembled, having its logs floated across Jackson Lake, and undergoing reassembly here. It is believed the original cabin was removed at the time the new one was constructed.

Why? This part of GTNP is little visited by humans and abundant in wildlife. (Don’t hike here without bear spray.)

How? From Grassy Lake Road in the John D. Rockefeller Memorial Parkway just north of GTNP, take the flattish Glade Creek trail for 7 miles to the Berry Creek Cabin.

Grand Teton National Park Cabin Logbooks

Logbooks provide fascinating glimpses into what happened at some cabins. A log from Upper Berry Creek includes an entry from a backcountry ranger who retreated to the cabin after being attacked by a bear. A log from Upper Granite contains day-by-day updates from an all-women trail crew in the 1970s about work they did to install the tool cache that now sits behind the cabin. Notebooks started in 1978 at the Lower Berry Creek and Moose Basin cabins include entries from Jim Bell, whose exact position at the park has been lost to history. He had no ranger number but was an employee of some type. In the logs he calls himself the “Berry Creek technician” and writes about rebuilding door and window frames, installing and maintaining a stove, and installing sheet metal to keep animals out at Berry Creek. Entries in the same logbook from rangers and other park staff reveal that Bell’s efforts were appreciated—there are numerous “thank-yous” dedicated to him. Bell’s time as the Berry Creek technician ended in November 1981. He does not explain his departure; his final entry merely reads: “Goodbye Berry Creek. I hope to see you again someday.”

THE SURVIVING CABINS in both Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks still serve some of their original purposes. In Yellowstone, backcountry cabins become home bases for rangers in the instances of emergency bear closures, fires, or changes in backcountry conditions. Also, rangers still use them while patrolling for poachers. According to Yellowstone historian Murphy, “Poaching is still a thing and I think any wildlife big game species is vulnerable.” (For example, in 2019 two young men were caught after killing a mountain lion in the park.) The cabins “are an important part of how we protect Yellowstone today and they’re a great part of our legacy,” Murphy says.

In the Tetons, both rangers and trail crews continue using the cabins. Trail crews tend to concentrate on the southern part of the park, Wonson says, while rangers spend time in the more sparsely used northern areas. Every summer in Grand Teton, trail and park crews doing restoration work stay in the Lower Berry Creek Cabin. The 2016 Berry Fire burned 21,000 acres in the area around the cabin; the structure was spared because park crews worked hard to save it. They applied a fire-resistant aluminum structure wrap, which looked like shiny silver tinfoil covering the entire cabin, installed a sprinkler system, and did a burn of the surrounding area to reduce fuels.

“It’s incredible the amount of work and planning that goes into backcountry management,” says GTNP’S Germann. “All functions of the park administration use the backcountry cabins. I think it’s part of the story of Grand Teton National Park and so it’s fitting that today we use them in a very similar manner to years and years ago. They were instrumental in managing places and they still are today.”

Annual routine maintenance is done on GTNP’s remaining cabins. This includes oiling logs, replacing shingles, switching out wooden roofs for more fire-resistant sheet metal, and replacing rotted logs. Park employees who use the cabins over the summer are instructed to do “really simple things,” Wonson says, “like brush the pine needles off the roofs, keep debris off of window sills, and maintain drainage so water flows away from the building.” Whether or not structural changes can be made without compromising historical significance is specific to each cabin and depends largely on what features or uses influenced the decision to deem it “historic” in the first place. Preservationists utilize a standardized procedure whenever considering such changes.

“The cabins have an uphill battle because they are in some of the worst locations as far as building maintenance goes,” says Wonson. “Any maintenance that would be routine in a normal building, you have that added layer of difficulty. You can’t just run to Ace [hardware store]. If you discover you don’t have what you need to fix the stovepipe, you need to take a whole day’s trip.” And wildlife can be a problem. GTNP learned that fire-resistant shingles have salt in them. How did it learn this? Some animals—maybe marmots—have gnawed on shingles.

To complicate matters even further, GTNP’s 2016 Historic Properties Management Plan says all five historic cabins will continue to be maintained and preserved according to wilderness policies. “Wilderness policies” means that sometimes hand—not power—tools must be used, among other restrictions. “We don’t fly in materials; we pack them in unless it’s the minimum required tool to complete something,” Wonson says. “We have to complete our preservation mandate while still preserving the wilderness mandate, too.” Currently, no major restoration or renovation projects are underway on any of the GTNP cabins. The most recent historic preservation report says they’re all in good to fair condition.

Yellowstone cabins, however, do need maintenance. The cabin on Peale Island, in the south arm of Yellowstone Lake, offers a good example of the difficulty of the work sometimes required to preserve these structures. The building is primarily used by park scientists and crews, but sometimes also used to entertain visiting dignitaries, including members of Congress, donors to park projects, and even former President Jimmy Carter. In the late 1990s the structure was determined to be unsafe and a fire hazard. Yellowstone spent $50,000 to remodel/repair the 432-square-foot cabin, which was built in 1940. Solar panels were installed to replace a generator and a new propane system was installed. Sheetrock replaced fiberboard walls. “It was mostly done to make it safe, not to make it nicer for VIPs,” then-park spokeswoman Marsha Karle told the Bozeman Daily Chronicle at the time.

While this work made the cabin safer from fire, it’s still not out of the woods. Today, it is threatened by shoreline erosion. Cultural resource specialist Osman says the park is documenting the cabin and completing a historic structures report in case it needs to be moved in the future. Concerning all of the Yellowstone cabins, Osman says, “It’s quite a process they go through to plan and implement these repairs to the buildings. Our backcountry rangers are shouldering a lot of that work and that burden.”

Wonson believes the effort is worth it. She has thought a lot about what these cabins add to the experience of visitors who come upon them, saying her mind goes to what humans do to eke out a living and how we choose to shelter ourselves in extreme environments. “It really gives you a sense of scale of how vulnerable and delicate we are, especially out here in this really rugged, harsh, amazing environment,” she says. “To me, it enhances the experience because it makes me think about my presence in the mountains and in the backcountry.” JH

See For Yourself, Grand Teton National Park Cabins

Death Canyon Cabin

Photo by Ryan Dorgan

What: This cabin was constructed in 1935 and nominated for

inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places in 1998.

When the idea of locating a cabin here was proposed by park

officials, it was opposed by a regional landscape architect who didn’t think it would get used enough to justify its expense.

Why: It’s on one of the park’s most popular trails. Make it your turn-around point on a hike part way up Death Canyon, or take a breather on the cabin’s porch if you’re doing the longer hike (about 8 miles one-way) to the 11,302-foot summit of Static Peak.

How: From the Death Canyon Trailhead off the Moose-Wilson

Road, the cabin is a 4.2-mile hike gaining approximately

1,800 vertical feet.

Upper Granite Canyon Patrol Cabin

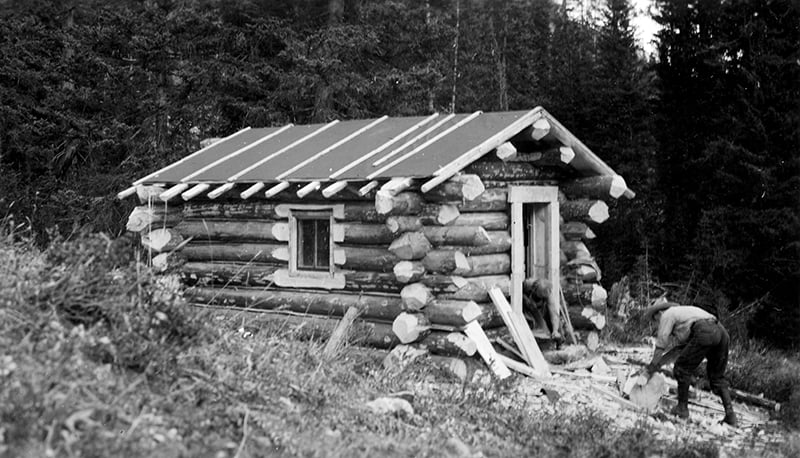

Photo Courtesy of Grand Teton National Park Archives

What? This cabin built in 1935 sits in the extreme southwest corner of Grand Teton National Park and is deemed historically significant due to its association with the park’s development and with the National Park Service’s “Rustic” architecture style. The chevron-cut ends of the logs are characteristic of cabins built by the Civilian Conservation Corps at the time, but it is believed this is actually a tuskers’ cabin, the only one still standing in the Tetons. An old photo labels it as such.

Why? Need to cool off in the heat of summer? You’re in luck. Marion Lake, a subalpine lake tucked in a cirque, is just 2.5 miles farther up the Granite Canyon Trail.

How? You can get here in more than one way. From the Granite Canyon trailhead at the southern end of the Moose-Wilson Road, it’s a bit under 10 miles round-trip. You can also take the Jackson Hole Mountain Resort Tram to the 10,452-summit of Rendezvous Mountain and hike down to the cabin, then hike out Granite Canyon and back to the base of the tram at Teton Village. This loop is about 13 miles.

See For Yourself, Yellowstone Park Cabins

Buffalo Lake/Boundary Creek Cabin

What? Constructed by the U.S. Army in 1912, this is the oldest cabin in Yellowstone.

Why? The chance to see a relic of our country’s first national park, plus the likelihood of solitude. Don’t expect to see many other folks on the trail.

How? You’ll want to make this 33.6-mile (round trip) out-and-back hike an excursion of at least one overnight. From the Bechler Ranger Station trailhead pass the Cave Falls Cutoff Trail and continue to the Boundary Creek Trail. At the junction of the Boundary Creek and Bechler River Trails, take the trail on the right (north) to follow a tributary of Boundary Creek; less than a mile past the junction, ford the creek. Around 8 miles from the trailhead, you’ll be treated to two waterfalls. Buffalo Lake, a shallow 20-acre lake lined with trees, is another 8 miles past these falls. Backcountry campsite 9A5 is on the lake’s shore.

Peale Island Cabin

Photo Courtesy of National Park Service

What? The first Peale Island Cabin was built in 1924 as part of Yellowstone Lake’s fish hatchery operations. Its successor, the cabin that still stands today, dates to 1940. It was built by the Public Works Administration for the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife (now the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service). Ownership was transferred to the National Park Service in 1961.

Why? It’s a cabin on an island in the middle of the largest high-altitude lake in the country. And it won’t be there forever. The building needs to be moved in the near future due to increasing lake levels and shoreline erosion.

How? Motorized craft are prohibited in this area of Yellowstone Lake, so you can visit Peale Island on a multi-day canoe or kayak trip or by hiking in with a packraft. Peale Island itself has no backcountry campsites, but sites 5L2 (Monument Camp, accessed by trail or boat) and 5L3 (Chipmunk Creek Outlet, accessed by boat only) are nearby.