Read The

Current Issue

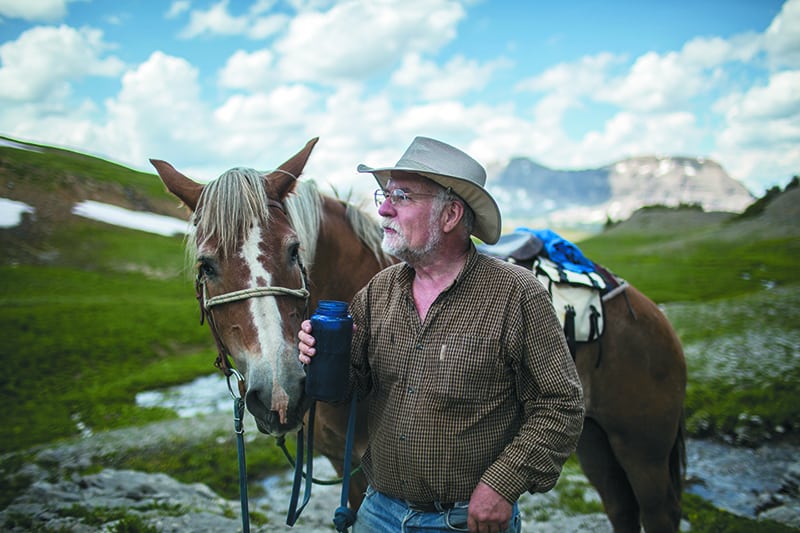

On the upper Gros Ventre, standing the test of time

In 1964 Loring Woodman’s parents bought the Darwin Ranch and Woodman launched a 50-year stint as its manager.

By Mike Koshmrl

Loring Woodman, who ran the Darwin Ranch for 50 years, takes a break with his horse high in the mountains near the headwaters of the Gros Ventre River, five months after selling the guest ranch. Photo by Ryan Dorgan

LORING WOODMAN WAS a New Jersey kid who’d fallen in love with wild Wyoming in the early 1960s. He’d notched formative early life experiences like summiting the 13,775-foot Grand Teton (at age 12) and summer adventures in Jackson Hole, which he helped fund by getting a job washing dishes at Trail Creek Ranch. When he was 21, he took his love for the area farther than most kids would or could: he convinced his parents to buy a 160-acre, far-flung guest ranch that was tucked along the banks of the upper Gros Ventre River. “I talked my family into buying it, and they had never seen it,” Woodman says of the Darwin Ranch, which he’d go on to manage for half a century. “I was trying to turn that place into a way of life for myself.”

Looking at isolated mountain properties in the greater Jackson Hole area in the early 1960s, Woodman found that the Darwin Ranch, then called the Hidden Valley Ranch, checked all the boxes. The Gros Ventre River’s meandering headwaters and a tributary, Kinky Creek, cut through the property, which was wholly surrounded by the Bridger-Teton National Forest (BTNF). The only way to access the property he’d quickly learn to love was a 5-mile-drive down a rutted two-track spur off Union Pass Road. “It was its isolation,” Woodman says; “… like living in Eastern Africa, basically—the enormous open space, mountains, wildlife, it’s not developed—and it still is. It’s absolutely wonderful country.”

Although some owners prior to the Woodmans had operated the Darwin as a guest ranch, it was in poor condition when they bought it. “Everything was rotting out, everything was leaking,” Woodman says. There were about seven buildings and a root cellar. Some buildings dated to 1901, when Fred Dorwin first homesteaded there. “All the buildings were sitting on the ground, and there were no footings and no foundations,” he adds.

His family paid Loring, then a recent graduate of Harvard University, $1,200 annually to maintain and manage the ranch. His parents’ relationship with the property got off to a bumpy start, and not just because it was a big investment: “They bought it in early July, and they got out there to look at what they bought in September,” he recalls. “Back then, the last 42 miles of that trip, all the way from Cora, were over dirt road. It just about gave them a nervous breakdown, but after about two nights of getting settled in there, they fell in love with the place just as I had.” The Woodmans supported their son’s unusual choice of profession, he says, because he had a passion for it.

Fred Dorwin submitted a Homestead Act claim on what is today the Darwin Ranch in 1901 and “proved up” the property by 1903. A misspelling somewhere along the line explains the Dorwin/Darwin disconnect; this error carries over to the Gros Ventre Range’s third-highest mountain, 11,647-foot Darwin Peak. But this might be for the best: In the pages of historian Fern Nelson’s This Was Jackson’s Hole, Dorwin is described as a “cranky old cuss” who was mostly avoided by other early Gros Ventre settlers.

Over his 50 years at the helm, Woodman transformed the ranch. He slowly improved the infrastructure, fortifying the existing buildings (which included putting them on foundations), remodeling cabins, and adding bathrooms and a hydroelectric system that ran off of Kinky Creek. Around the turn of the 21st century, after navigating a contentious, nine-year-long approval process, he convinced the BTNF to improve the 5 miles of road that accessed the property, which was badly deteriorated, partly from a landslide. (Kinky Creek Road, via Union Pass, is the only way to drive to the Darwin, though there are horse and hiking trails and snowmobile routes that access the property from the Gros Ventre Road.)

In its earliest years under Woodman, the ranch was an easy sell with hunters. Though there were guests both seasons—summer and fall, that is—from the get-go, the summer experience took a bit more time to catch on. The clientele evolved along with the culture, which Woodman carefully cultivated into a unique brand reminiscent of old West-style Jackson Hole guest ranches like the Whitegrass and the Bar BC. “There were log cabins and nothing fancy,” Woodman says. “People came for the experience in the outdoors and the camaraderie.” Summer guests were a mixed bag, from teachers to doctors and lawyers, but almost everyone had something in common: They’d come to love the Darwin as much as Woodman had. About 95 percent of guests were regulars. “Essentially, people made reservations for next year as they were leaving,” Woodman says. “We were completely full. I didn’t advertise for the last 25 years.” That tradition continues to the present, with local residents like Luther Propst and Liz Storer and Paul Hansen and Kay Stratman faithfully logging another week as Darwin guests every summer.

Woodman’s parents deeded him the Darwin in 1972. (The property had climbed in value and they were planning ahead to avoid an estate tax that could force the family to sell.) By the middle of the first decade of the 21st century, after 40 years managing the ranch, Woodman was near typical retirement age and he started looking to sell. In 2008, a sale was in the works and contracts drawn up, but the Great Recession struck and foiled the transaction. A 2012 auction at the Wort Hotel fell flat when no one surpassed the minimum bid. Then, in 2014, exactly 50 years after Woodman started as manager at the Darwin Ranch, he finally found new owners to pass it on to, Kathy Bole and Paul Klingenstein. The couple already owned and ran the Cody-area Ishawooa Mesa Ranch, a working cattle operation. Woodman didn’t have preconditions for a buyer, but if he did Bole and Klingenstein would have met them. “They’re great conservationists and they want to take care of the place—and they have the wherewithal to do so,” Woodman says. “I think it’s extraordinarily lucky that we found people like that to buy it.”

Like Woodman, “Paul was particularly drawn to its remoteness,” Bole says. “People say that it’s the most remote private land in the Lower 48 states. There’s 3 million acres in the Bridger-Teton, and [the Darwin] is in the middle of it.” Klingenstein and Bole enlisted their son, Oliver “Ollie” Klingenstein, to help manage the property. Like Woodman 50 years prior, Ollie was in his early 20s, just out of college, had a love for the outdoors, and wasn’t from the area. Guests drawing comparisons between the two came naturally.

“We learned it all, before we changed too much,” Ollie says. “We learned why guests came back every year and why this place was so special to so many people. We changed it slowly over time to make it into our place, but there’s a lot of that model that Loring cultivated over 50 years that still exists—there’s no doubt about that. [Loring] cultivated something that I think was just right.” JH

An undated photo of the original Darwin Ranch lodge.

Darwin Ranch’s main lodge. Courtesy Photo

The Darwin Today

The Darwin is still a guest ranch. Kathy Bole and her son Ollie Klingenstein split its management duties: Bole oversees most indoor things—lodge operations, the kitchen, cabins, and reservations—while Ollie, who is an EMT and farrier, manages recreation and the ranch’s herd of horses, physical plant, hydro-power system, and rotational grazing program. As was the case under Woodman, the Darwin has room for 16 guests at a time and is open from late June through mid-September for summer guests and though late October for hunters.

A hallmark of the Darwin experience is an acknowledgement of its tradition: unstructured days. As has been the case since Woodman’s guests first arrived in 1965, guests’ time at the Darwin today is unencumbered by scheduled activities; they’re given free rein to hike, fish, and even go out on horseback to explore the Gros Ventre Wilderness on their own. The Darwin is one of the last guest ranches in the West that allows unchaperoned riding, the current owners say. “I hear stories about the old-time Western guest ranches, and I think a lot of them were kind of like us,” Ollie says. “This is an experience that doesn’t really exist anymore [elsewhere], and it’s a nod to the classic old-style experience where you can go ride your horse around in the mountains until it gets dark.”

Bole and Klingenstein have made the Darwin their own, from tweaking décor to updating infrastructure that Woodman himself overhauled decades ago. A new option for ranch guests is a fully supported glamping experience at the Upper Falls Camp. Their family background includes sustainable agriculture, and Bole, a former chef, sees to it that the Darwin’s menus include as little store-bought food as possible. Beef, poultry, and produce come from the family’s Ishawooa Mesa Ranch and some of the pork sources can be seen roving the Darwin property. (Last summer, friendly swine named Lewis and Clark oinked and grazed around the property before ending up on dinner plates.) Coffee and other goods are sourced as locally as possible, often coming from Jackson. darwinranch.com

National Historic Register?

The Klingensteins commissioned Pinedale historian and writer Ann Chambers Noble to prepare an application to list several of the Darwin’s oldest structures on the National Register of Historic Places. (This process formally started in February 2020, and the application was still pending as this edition of Jackson Hole magazine went to press.) Chambers’ research is finished, though, and it makes a compelling case that the buildings have historic significance: Some are representative of the Anglo settlement era and others are excellent examples of western craftsman architecture.

While interviewing people for a narrative summarizing its historic significance, the term “intellectual dude ranch” was thrown around to describe the Darwin. “The living room is lined with great books, and in that room intellectual conversations occurred,” Chambers wrote. “Guests who enjoyed reading and discussing deep, thoughtful topics have long been drawn to the place. The ranch ownership consisted of educated men and women.”

Who owned the Darwin when?

1901

Fred Dorwin submits a Homestead Act claim for the 160 acres.

1903

Dorwin “proves up” the property.

1917

Dorwin sells to Winnifriede and Thomas Ray Black, who use the property as a private hunting lodge.

1923

Knowlton McKinley “Bob” Robinson and his wife, Wafie, buy the Darwin and operate it as an upscale dude ranch focused on hunting and fishing.

1940

The Severence family buys the ranch as a private getaway and hunting property.

1946

Phillip and Lalita Norton buy the ranch and keep it as a private retreat. “The Nortons were popular ‘gossip-material’ for Sublette and Teton County residents,” historian Ann Chambers Noble wrote. “They are remembered for their ‘stuck-up’ attitude and pampered lifestyles, available to them because of their financial means. Later owner Loring Woodman remembers using lobster crates for storage that were left

by the Nortons—presumably from lobster deliveries.”

1957

Widow Ailee McIntyre buys the ranch, renames it Hidden Valley Ranch, and re-establishes it as a guest ranch.

1964

Charles and Helen Woodman buy the ranch at their son Loring’s behest, change the name back to the Darwin Ranch, and pay Loring $1,200 a year to manage it as a guest ranch. Paying guests first arrive in 1965.

1972

The Woodmans deed the ranch to Loring.

2014

After managing the Darwin for 50 years and transforming it into one of the most iconic guest ranches in the West, Loring Woodman sells it to Kathy Bole and Paul Klingenstein. The couple hires son Oliver as ranch manager and continues to operate it as a guest ranch.

Dates and information from Ann Chambers Noble’s National Register of Historic Places application