Read The

Current Issue

From flood to fire to condemnation, the attempted erasure of Kelly has been the town’s one constant.

Photos and text by Ryan Dorgan

IN 1978, DUNCAN Morrow, a National Park Service (NPS) spokesman, told the Jackson Hole News that there were two things giving him headaches. The first was “inholders”—some 32,000 people who owned private real estate within the boundaries of America’s national parks. The second headache Morrow offered up without hesitation: “Kelly, Wyoming.” At that time, Morrow’s two pains went hand-in-hand; the unassuming community of about one hundred people on the Gros Ventre River on Jackson Hole’s eastern flank was the center of a nationwide battle between private landowners and a federal government’s land-acquisition program.

Kelly, as we know it today, was subdivided in 1937, ten years after a flood wiped out almost all of the community and thirteen years before Grand Teton National Park was expanded to encompass it. A massive landslide in 1925 created an earthen dam across the Gros Ventre River; in 1927 this dam failed and all but three of Kelly’s buildings—its school and the Episcopal church and its parsonage—were washed away. Six Kelly residents died in the flood.

Of the 181 lots plotted in 1937, seventy-six of them (about 42 percent) have been acquired by the NPS. These are now part of Grand Teton National Park (GTNP). For years (and to this day), the NPS bought inholdings in Kelly and in national parks across the country under a “willing-seller/willing-buyer” arrangement, often offering a cash deal with a lifetime lease that allowed residents to remain in their homes until they died, after which their homes would be demolished and the lots left to return to a natural state. To this day, 2.6 million of the 85 million acres that fall within NPS boundaries remain privately owned, with 884.3 of those private acres in GTNP.

While the vast majority of Kelly’s inholders sold their homes to the NPS voluntarily, the pressure picked up in the mid-1970s. At that time, with land values continuing to rise, Congress allocated $450 million over three years to the NPS for the purpose of purchasing all inholdings across federal lands nationwide. A career real estate man named Robert Lunger was brought to GTNP to buy up inholdings on behalf of the NPS. “Willing-seller/ willing-buyer” remained the park service’s public position, but two landowners in Kelly were told by Lunger that their land would be condemned under eminent domain after plans to build cabins on their properties were deemed incompatible with the park’s mission to preserve undeveloped lands within its boundaries. “It was all in a very threatening way,” said a resident who Lunger visited at work. “It wasn’t ‘We wish you wouldn’t do that.’”

By the end of the 1970s, public pressure and changing park service priorities eased the push to erase Kelly, and by 1984 a new GTNP land-acquisition plan moved Kelly to the bottom of its priority list, recommending deferring any further acquisition of private property in Kelly so long as land uses compatible with the Teton County Comprehensive Plan continued.

Today, Kelly remains a small community reflective of its past, a patchwork of attempted erasure locked in time. Million-dollar houses sit beside modest cabins and NPS-owned vacant lots, while dilapidated homes signed over to the NPS decades ago continue to fall into disrepair, waiting for just enough funding for the bulldozer to return them to the earth.

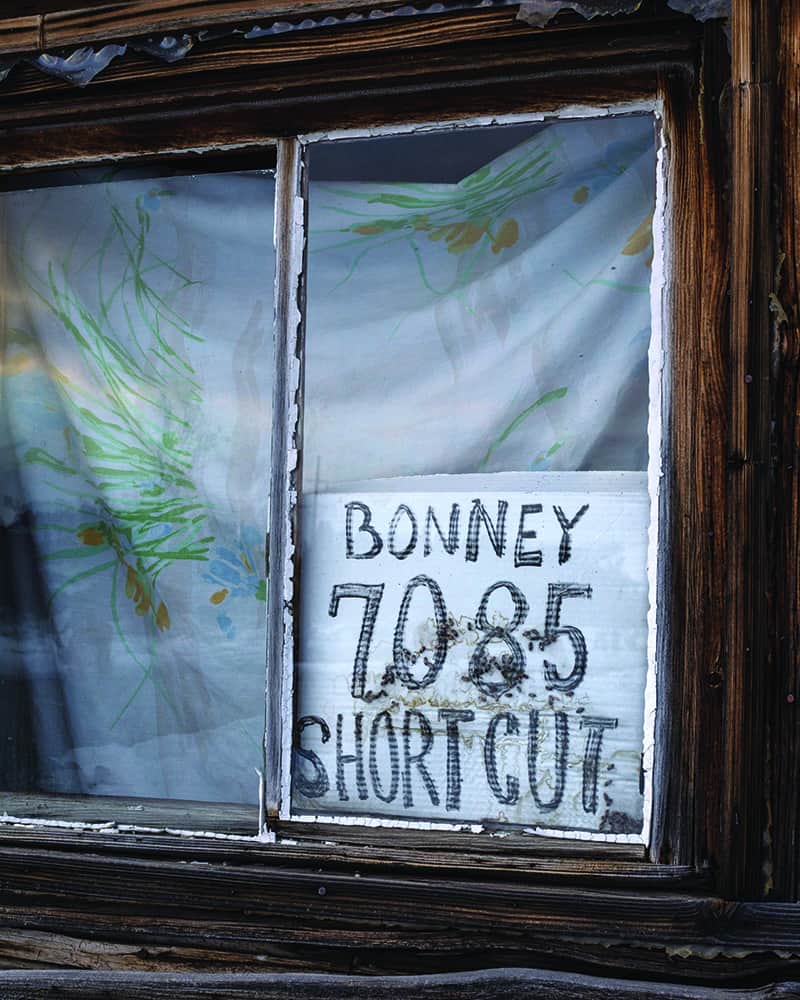

THE BONNEY HOUSE

Lorraine and Orrin Bonney spent many summers in this cabin, which they bought from Oscar Seaton. If you’ve spent any time up high in Wyoming’s mountains, chances are you’re familiar with the Bonneys. The couple met on a mountaintop in the early 1950s and spent most of the rest of their summers in the alpine, exploring and writing guidebooks so that others could share in their experiences. They eventually wrote nearly twenty guidebooks; their first was published in 1960, the exhaustive Guide to the Wyoming Mountains and Wilderness Areas. Because of their combined explorations in the Wind River mountains, Wyoming’s largest range, a pass between the Titcomb and Dunwoody valleys was named after the couple. In the Tetons, a pinnacle on the North Ridge of the Middle Teton also bears the Bonney name. Orrin was an attorney in Houston, Texas, but the family lived for their summers in Jackson Hole. Before buying this cabin, they stayed in a tipi near Jenny Lake. The Kelly cabin jokingly came to be known as “Fort Bonney.” In 1976, the Bonneys sold their “fort” to the National Park Service but took advantage of the NPS’s policy allowing former owners of inholdings to live in their homes until their death. Orrin died in 1979, and Lorraine lived and climbed for another thirty-seven years, dying in 2016 at the age of ninety-three. (She lived in this cabin until at least 2012.) In 2019, the two were inducted into the Wyoming Outdoor Hall of Fame.

THE DRISKELL HOUSE

Dean and Iris (Carlson) Driskell bought this place from Iris’s parents. Dean was a contractor and had a cinder block shop on the property that’s still standing. In 1946, he and his nephew Glen “Bob” Wiley built one of Jackson’s first motels, the D&W, which eventually became the El Rancho Motel and is now part of the Anvil Hotel. In 1948, the men built research facilities in Moran for the Jackson Hole Wildlife Park, which today is part of Grand Teton National Park. To keep busy in the winter, Dean and Bob built snow planes in a cabinet shop in Jackson. This shop still stands; it’s the long building behind the former Jackson Hole Historical Society cabin at the intersection of Mercill and Glenwood Streets in downtown. The Driskells sold their Kelly home to the National Park Service (NPS) in 1984 but lived in it until 2003, when Dean died. (Iris died in 2010.) A neighbor said the house is now boarded up because kids broke in and started a fire on the living room floor one night after the Driskells had sold and moved out.

THE LITTLE HOUSE

THE FULLERTON HOUSE

Little is known of Sue Fullerton, who signed this home over to the National Park Service in 1978. It is not known how long she lived in the house after this. Fullerton helped to develop the geographic information system (GIS) for Grand Teton National Park and was recognized in 1993 for her accomplishments in the GIS program. She was a docent at the National Museum of Wildlife Art and was involved in the Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance’s annual silent art and antique auction. JH