Read The

Current Issue

In rock climbing, the challenge and joy are in the journey rather than the destination. No experience required.

// By Molly Absolon

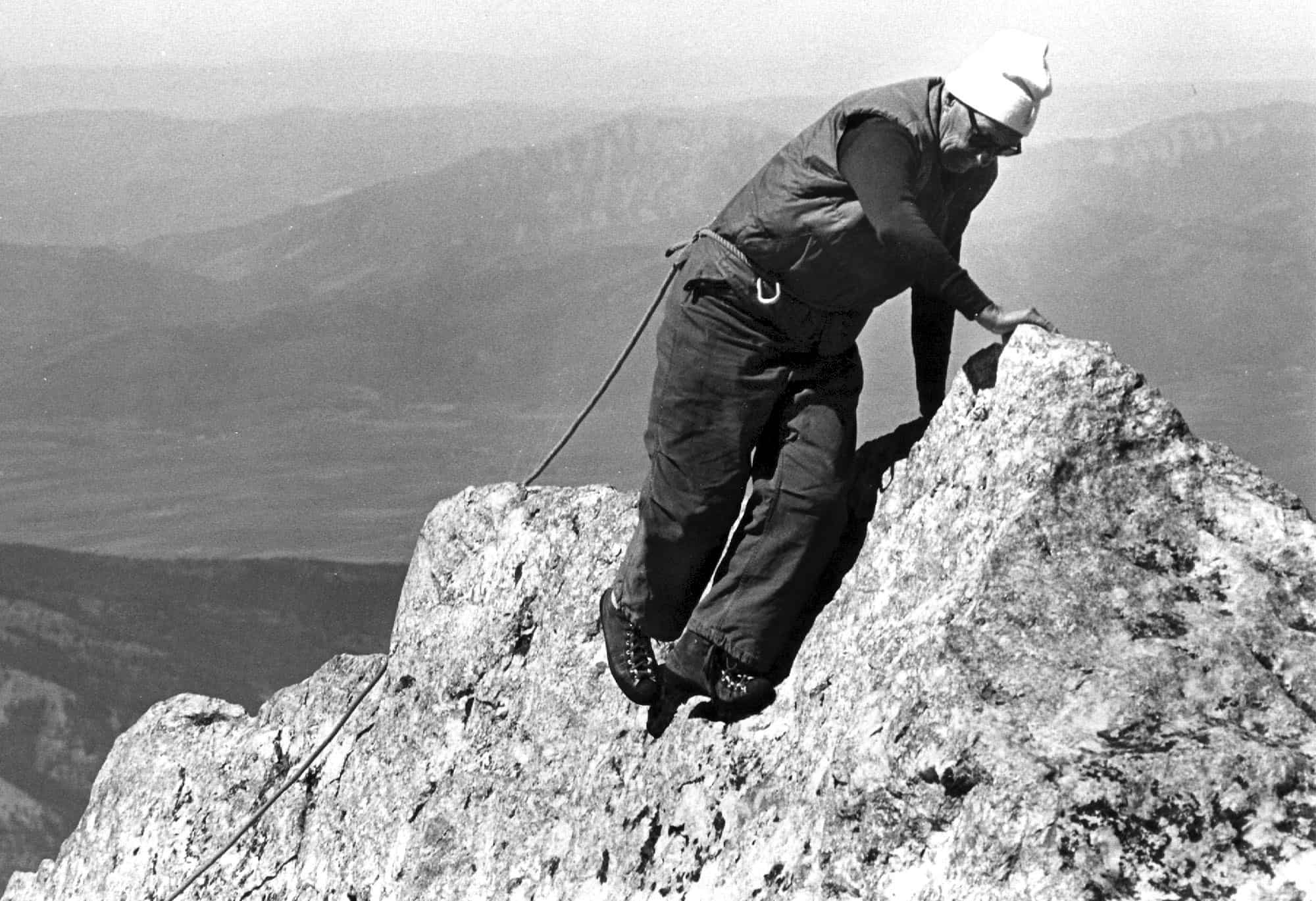

Rock climbing, at its most basic, is ascending cliffs, boulders, or artificial walls using one’s hands and feet. For some people, it doesn’t get much deeper than that, but for others, climbing is an art form, requiring physical strength, gymnastic ability, focus, vision, mental control, problem-solving ability, endurance, and skill. Elite climbers say when everything comes together, climbing is about achieving a state of flow as focused as that of any yogi. “I used to be a marathon runner,” says climber Chris Ballard. “When you run marathons, you spend hours working through your issues. Climbing is different. When I am climbing, I’m not thinking of anything else; all I can do is focus on the moment. It’s like a natural form of Adderall. I love that about the sport.”

Nonclimbers often assume rock climbing is scary and dangerous, and there are certainly hazards inherent in ascending cliff faces, but the numbers don’t actually support the idea that climbers are daredevils. The Outdoor Industry Association’s most recent participation report shows that roughly nine million people climb each year and there are, on average, about thirty climbing-related fatalities annually. Between 2007 and 2018, Grand Teton National Park reported a total of fifty-four deaths out of thirty-four million visitors. Of these fatalities, twenty were climbers, which comes out to an average of less than two people per year. (For comparison, in June 2017 The Daily Californian’s Daily Clog reported that vending machines fall on top of and kill an average of thirteen people a year; twenty-four people per year die from being hit by champagne corks; messy handwriting, especially of doctors, leads to 7,000 accidental deaths through mixed-up prescriptions; and 2,500 lefties die trying to use equipment designed for right-handed people.)

The great thing about climbing with [a guide] is that technical rock routes are possible for people like me who don’t have any experience.”

—Michelle Escudero

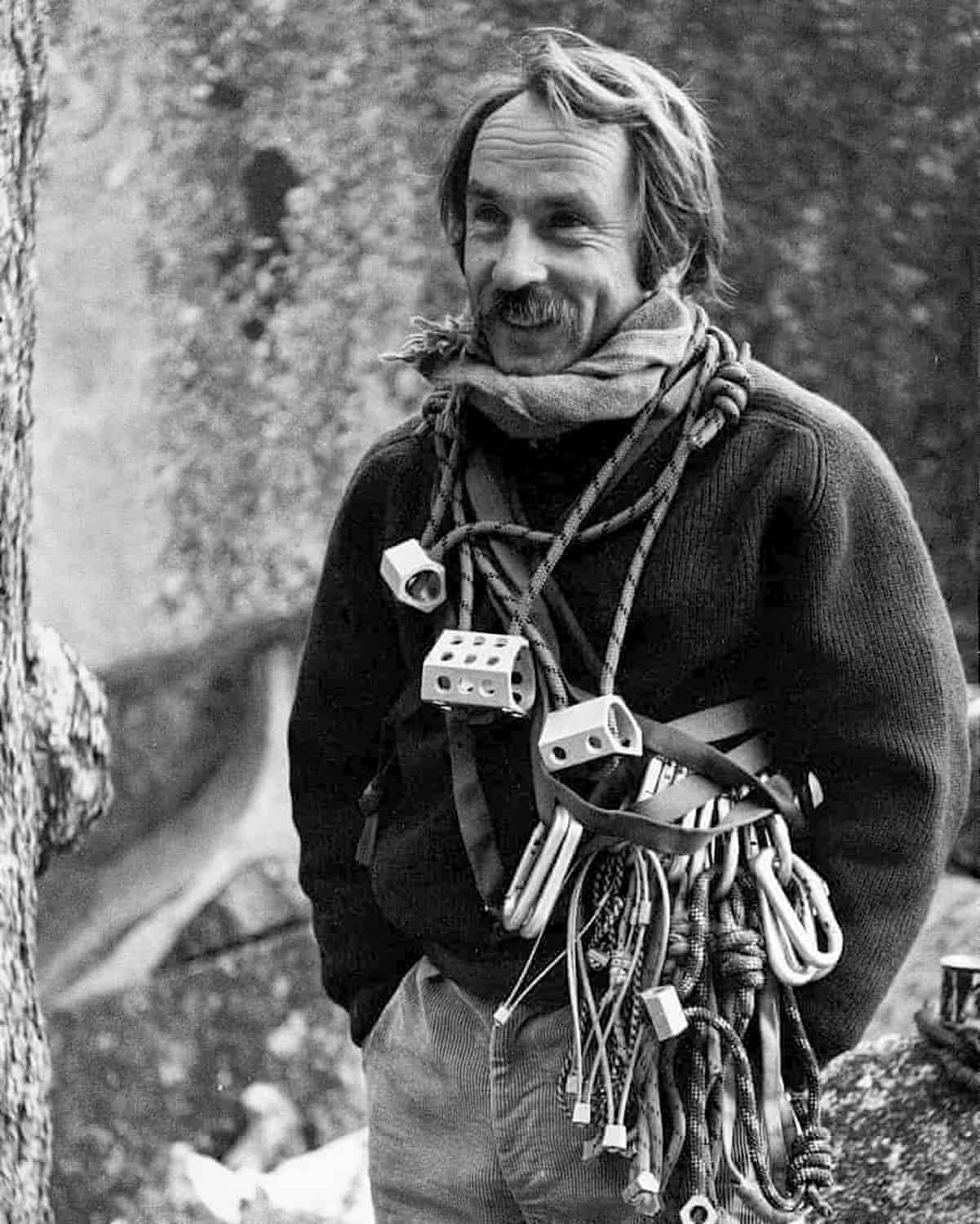

The Tetons and the Wind Rivers are two climbing areas to which people travel from all over the world, not only for hard routes that challenge the elite, but also for scores of easy to moderate rock climbs that allow people of all abilities to have the incredible experience of climbing in the alpine. Of course, roped alpine routes require a basic level of competency, but this doesn’t mean you can’t go if you lack experience. It just means you’ll need to hire a guide. Two guide companies operate in Grand Teton National Park and the Wind Rivers: Exum Mountain Guides, founded in 1926 by Glenn Exum and Paul Petzoldt; and Jackson Hole Mountain Guides (JHMG), founded in 1968 by Jackson Hole ski instructor and guide Barry Corbet. “The great thing about climbing with [a guide] is that technical rock routes are possible for people like me who don’t have any experience,” says Michelle Escudero, who climbed the Grand Teton with JHMG and three childhood friends, all of whom had little to no climbing skills. “After we finished the climb, I remember thinking it was incredible that we actually did it. But we felt totally safe the whole way.”

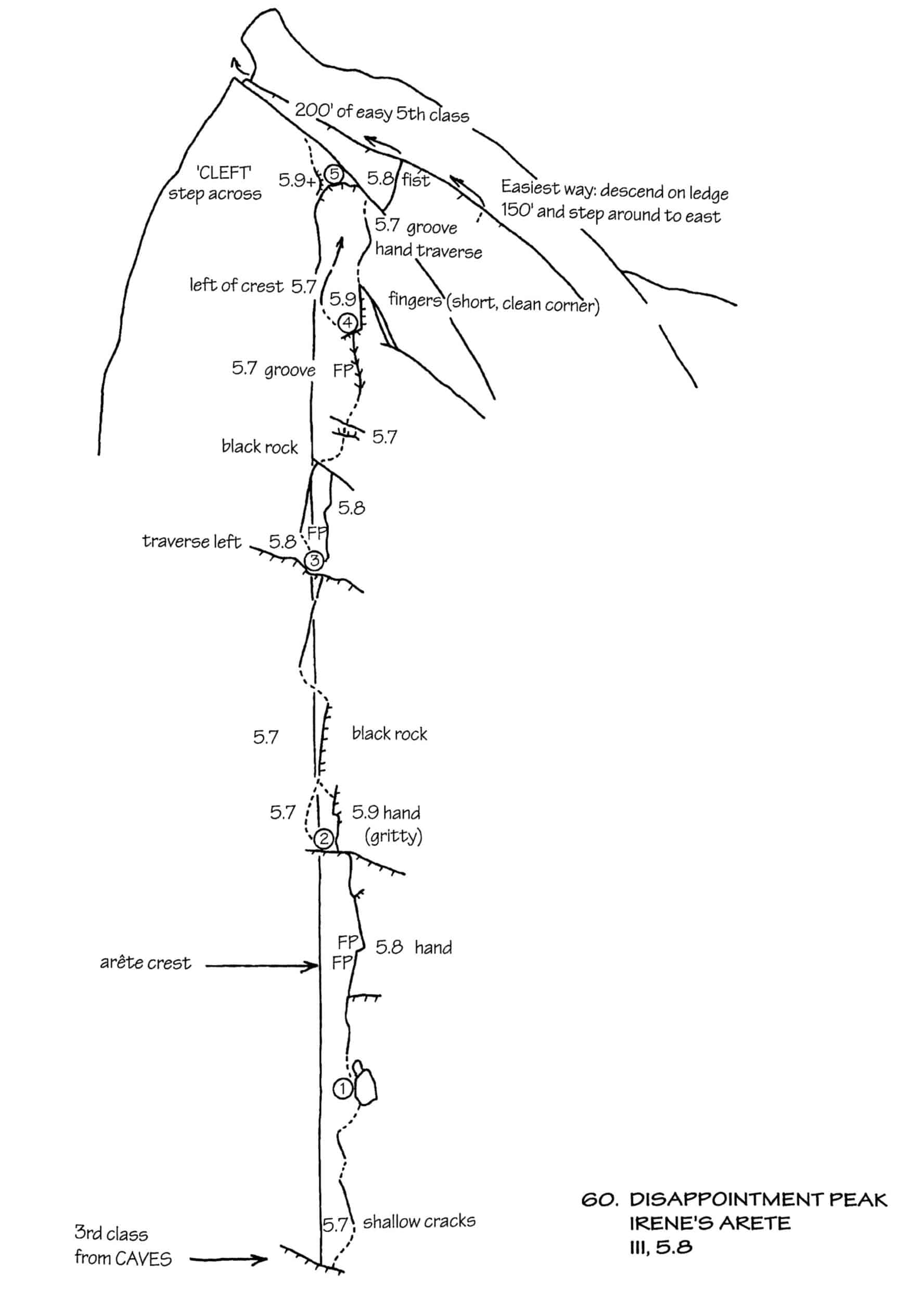

A Climber’s Guide to the Teton Range: Leigh Ortenburger, a climber, historian, and photographer, first began gathering information for a climbing guide to the Tetons soon after he arrived in the area in 1948. His nearly-400-page “magnum opus,” published in 1956, contains descriptions, hand-drawn topo maps, photographs for more than ninety routes, and a wealth of meticulously researched historical information about the men and women who developed climbing in the Tetons. The book’s third edition, published posthumously under the guidance of former Grand Teton National Park climbing ranger Reynold Jackson, came out in 1996 and continues to be the most comprehensive guide to climbing in the Tetons.

“When I am climbing, I’m not thinking of anything else; all I can do is focus on the moment. It’s like a natural form of Adderall.I love that about the sport.”

—Chris Ballard

Teton Climbing History

Rock climbing as a sport grew out of mountaineering. The earliest alpinists sought out “walkups,” mountains that required nothing more than feet to reach the summit. As these easier peaks were conquered, more adventuresome climbers began to look for harder challenges, until, by the 1950s, something shifted. A new breed of climber began moving away from peak climbs toward finding lines up steep cliffs. Many of these new routes didn’t get to the top of anything. The goal was the journey, not the destination, and rock climbing became its own sport.

That new sport evolved quickly in places like California’s Yosemite National Park, the Shawangunk mountains in New York, and Colorado’s Front Range. Here, men (and the early pioneers were almost exclusively male although today men and women climb equally difficult grades) at the cutting edge of climbing were developing techniques and equipment that allowed them to ascend previously unclimbable cliffs. It didn’t take long for these innovations—which include things like sticky rubber shoes, steel pitons, removable “clean” protection, and dynamic climbing ropes—to spread to other climbing areas in the country, including Wyoming’s Tetons and Wind River Mountains. By the summer of 1960, about 2,300 people came to the Tetons exclusively to climb, according the National Park Service.

The clean granite walls found in the Tetons and the Wind Rivers gained fame among climbers, and many of the early rock routes were put up by names well known in climbing lore: Fred Beckey, Yvon Chouinard, Barry Corbet, Peter Lev, Mike Munger, Leigh and Irene Ortenburger, Richard

Pownall, Al Read, Royal Robbins, and Willy Unsoeld. These innovators didn’t care about the high peaks. They wanted hard climbs that tested their physical skill and mental fortitude, and sought that challenge on cliff faces that led to nowhere: the south ridges of Mount Moran and the buttresses in Death Canyon and the south side of Disappointment Peak. Some of the most important climbs put up between the late 1950s and the 1970s continue to be classics; they include the Snaz, Raven Crack, Irene’s Arete, and the South Face of Symmetry Spire.

Climbing in the Tetons continues to evolve as advances in equipment and training transform cliff faces that were previously considered impossible into doable. Consider, for example, the North Face of the Grand Teton. In 1931, Fritiof Fryxell and Robert Underhill climbed what was then considered to be the most difficult rock route in the Tetons. Their ascent required some clever use of shoulders and pitons to overcome obstacles, but eventually the pair succeeded in reaching the summit, rating the climb 5.8. Today, 5.8 is considered moderately difficult, but then it was the peak of achievement and the only apparent way to ascend the Grand’s steep north face. But, in 2002, a new route went up next to this original line. Ascending a series of cracks that Fryxell and Underhill would have deemed impossible, Greg Collins and Hans Johnstone established the first 5.12 on the Grand Teton, a seven-pitch climb they named the Golden Pillar. And so, each year, new blank spots on the map are filled in with visionary lines that exceed the previous generation’s idea of the possible as climbing skill, equipment, and training continue to push the edge further and further into the impossible.

Barry Corbet

The name of the founder of JHMG, Barry Corbet, might be familiar to skiers. One of the most iconic, and difficult, ski runs at the Jackson Hole Mountain Resort is Corbet’s Couloir. Corbet spotted the narrow, north-facing funnel of snow high on Rendezvous Mountain and said, “Someday someone will ski that.” He, however, never skied the line. Neither did he get to achieve his goal with Jackson Hole Mountain Guides—to focus on education rather than simply moving people to the top of a peak. Three months after JHMG was founded in 1968, Corbet was paralyzed in a helicopter accident, and he subsequently sold the business.

Try climbing for free and with low stakes at Teton Boulder Park. In Phil Baux Park at the base of Snow King Mountain in downtown Jackson, there are two large artificial boulders covered with climbing holds. For a challenge, try to follow routes marked with colored tape, or just grab any hold and start to climb.

Irene’s Arête, a classic 5.8 climb on Disappointment Peak in Garnet Canyon in GTNP, is named for Irene Ortenberger (Irene Beardsley after a second marriage), who made a first ascent of the line in 1957 with John Dietschy. Ortenberger continued to put up hard climbs in the Tetons, including, in 1965 with Sue Swedlund, the first all-female ascent of the North Face of the Grand Teton. (Also, in 1965, she became the fourth woman to graduate from Stanford University with a PhD in physics.) In 1978, she was one of the first two women, and the first Americans, to climb Annapurna I, an 8,000-meter peak in Nepal. The American Women’s Himalayan Expedition spent a year raising funds for the climb, including selling t-shirts with the slogan, “A Woman’s Place is on Top.”

Classic Teton Rock Routes

5.6 Southwest Ridge, Symmetry Spire: A beautiful, direct, and impressively steep route for its grade.

5.8 Irene’s Arête, Disappointment Peak: A knife-edged ridge known for its excellent rock quality, ease of access, and outstanding climbing.

5.9 Open Book, Disappointment Peak: The opposite of Irene’s Arête in nature, this climb follows a crack/dihedral system on good rock with airy belays and spectacular exposure.

5.10 Snaz, Death Canyon: Classic crack climbing with lots of variety and a technical crux through a roof on the fourth pitch.

5.11 South Buttress Right, Mount Moran: Pitch after pitch of amazing granite, with an exciting fingertip traverse crux.

Yosemite Decimal System

The original Yosemite class system was created by the Sierra Club in the 1930s to indicate the difficulty of various hikes in the Sierra Nevada and has since been adopted elsewhere, including the Tetons.

Class 1: Hiking

Class 2: Off-trail hiking

Class 3: Scrambling that requires the use of hands

and feet

Class 4: Scrambling with exposure; some people

may want a rope

Class 5: Technical climbing

As technical climbs became more difficult, Class 5 was broken into rankings from 5.0 to 5.9. That scale broke down in the 1960s when climbers began putting up routes that were more difficult than the hardest existing 5.9. The grade now goes to 5.15.

5.0–5.4: Easy climbing

5.5–5.6: Easy moderate

5.7–5.9: Moderate

5.10–5.12: Advanced

5.13–5.14: Elite

5.15: Virtuoso. Very few climbers have climbed 5.15

as of 2021. JH